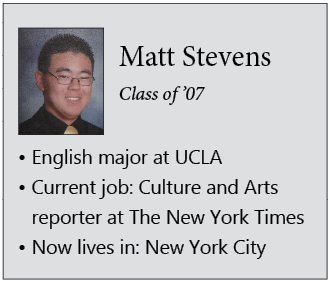

Stevens in the Newsroom

From Nexus to NY Times, Stevens keeps reporting

[metaslider id=11015]

Each morning in seventh grade, Matt Stevens lumbered downstairs, grabbed a cup of coffee from his Mr. Coffee coffee pot, and helped himself to a plate of Eggo waffles. Stevens flipped to the sports section in The San Diego Union-Tribune to check how the Padres did the evening before.

Before he knew it, it was 7 a.m. already. He spiked his mushroom haircut with gel, threw on his AND1 basketball shorts, and the boy with thick, brown, tortoise-shell glasses was out the door by 7:15, waiting for his carpool.

Finding a story

As Harry Potter grew a year older, so did Stevens. Engrossed by the wizarding world, Stevens stood in excruciating lines at Barnes and Noble to live vicariously through Harry while his own head was furrowed in a book.

While fiction had initially sparked his imagination in middle school, nonfiction entranced him. Even when he only intended to glance at the paper for box scores, his eyes would scan the page and land on sports columns from Nick Canepa in The San Diego Union-Tribune.

“I think reading the newspaper gave me a real appreciation for nonfiction writing pretty early [on],” he said. “I didn’t differentiate for a long time between literature and nonfiction stuff, but the thing that I always loved the most in my adult life, now, is nonfiction.”

Stevens said that in middle school, he never thought he was particularly good at writing nor was he passionate about it, yet he loved reading nonfiction. As he gazed at his course request in eighth grade, his interest in reading newspapers inspired him to check a box next to Journalism 1.

In a writing exercise for that class his freshman year, journalism and English teacher Jeff Wenger led The Nexus staff in a softball game that they took notes on. They interviewed each other afterward about the game and were instructed to write a sports story, which Stevens said he excelled at.

“That was really illustrative because [for] people who had never read a sports article, it was very difficult for them,” he said. “Because they didn’t know what language to use or how to do it. And I remember that was probably the time when I felt most like, ‘oh, maybe I could do this.’ With the sports article, it felt like I could close my eyes and just write a story about this dumb softball game that we played. Yeah, I had read so many of those articles growing up.”

Naturally, Stevens was more inclined to write sports stories. Having lived in Chicago in the ’90s during the Chicago Bulls’ prime, Stevens once believed he could “be like Mike.”

Stevens played recreational basketball in the Rancho Peñasquitos Basketball league (RPB) from third to eighth grade where he averaged an unimpressive 25 points a season. With his rec-spec prescription glasses on the court, non-degenerative cerebral palsy, and overall gracelessness, Stevens knew he could never be Michael Jordan, so as the years went on, he chose instead to write about athletes.

Using his press pass for The Nexus to gain free admission to Westview sports games for enjoyment, Stevens would often “rail on the referees” in an attempt to help motivate Westview athletes and demoralize the opposing team.

“I recall that Bob [McHeffey], who was the girls basketball coach at the time and also my AP English teacher, pulled me aside after one of the girls basketball games in which I had been acting obnoxious,” Stevens said. “I had used my press pass to get into the game, and he pulled me aside and tugged me by the shirt collar. [McHeffey said something like,] ‘You can be as much of an asshole as you want up there, but not when you’re wearing this.’ And he yanked my press pass, then just tossed it back down at me and stormed off.”

In another instance during Stevens’ junior year, former AP Calculus teacher Sanjevi Subbiah was holding a review session for the upcoming AP exam. After Stevens grew tired of the easy problems other students asked, he stormed out of the room.

The next day, Subbiah pulled him aside calling his actions selfish and inappropriate. Stevens said he is now appreciative of that incident, because Subbiah went beyond teaching about derivatives and limits that day and instead taught him how to be a good person.

Teachers like McHeffey and Subbiah held Stevens accountable for his actions in high school, teaching him lessons that resonated with him for longer than the lessons he learned in their classrooms. Even after graduating, the profound impact Wenger had on him is apparent.

“Nothing has been more important than sort of that bedrock foundation that Mr. Wenger laid down,” he said. “My experience with The Nexus was so formative that I really thought for a long time that I would want to become an English and journalism teacher, a lot like Mr. Wenger. Specifically, if it could be swung, I would be delighted to come back and take his job. All of that goes to just how incredible the experience of being on The Nexus was, how close my ties were with the people that I met there, and how much I thought of Mr. Wenger.”

As Stevens rose the ranks from a staff writer his freshman year, sports editor his sophomore and junior year, and editor-in-chief his senior year, he blossomed. The stories he wrote helped him view the world more empathetically and justly.

During his senior year, The Minutemen, an extremist anti-immigration group partly consisting of parents from Westview, participated in a protest. Stevens said he had to put his biases aside as he captured the viewpoint of a starkly anti-immigrant mom.

Stevens said his interest in journalism began selfishly, to indulge in sports experiences. However, through writing for The Nexus and observing the individuals covered in the paper, like his neighbor who was a foster kid, he came to realize how powerful journalism could be.

By graduation, he had wallflowered from a clumsy middle-schooler who wandered the library alone and bought Airheads at the student store to a high school Homecoming king and a leader on his way to UCLA.

Creating a draft

As an English major at UCLA, Stevens fantasized about the extraordinary games he would witness and write about. With hundreds of people technically on UCLA’s newspaper, The Daily Bruin, only about 50 staff members stayed in the newsroom for up to 30 hours a week, fueled by Panda Express and the need for sleep, to finish the paper the night before it was published.

“I think the newspaper was in a lot of ways more professional [than The Nexus given that it was] the third most-circulated newspaper in all of Los Angeles,” Stevens said. “Because of the pure number of white copies that we printed and put on the newsstands every day, but I always felt that I was trying to bring standards and practices from The Nexus and apply them to The Daily Bruin. I would look at our newspaper and be like, ‘Why is there not a pica [of space] here?’ So again, I think I was probably very annoying to a lot of people on our newspaper staff — sort of a know-it-all — but I think that came out of what I felt was just really excellent training in high school.”

When he accepted the position of assistant sports editor for The Daily Bruin, because they published each week during the summer, he drove from his parents’ house in San Diego to Los Angeles each Saturday morning.

Although Stevens gravitated toward writing sports articles, he began to become more compelled by human-interest stories that intersected his love of sports and the nuances of the human spirit.

Sports writing was like his first draft, but his refined draft that he was working up to — sports feature writing — was still being written as Stevens traveled to Yaoundé, Cameroon on the Bridget O’Brien journalistic scholarship, which granted him a fully-funded trip to pursue a story through a global lens but with local impacts.

Recognizing that two of UCLA’s best basketball players at the time, Luc Richard Mbah a Moute and Alfred Aboya were both from Cameroon, Stevens sought to find out why so many basketball players from Africa were showing up on college campuses.

He found that through shady money exchanges, players got into the country, but he also covered the African players that were left behind.

“Cameroon was a vibrant, beautiful country full of generous people,” Stevens said. “I think the combination of being 20-ish years old, out in a foreign country with just one friend for support, trying to report a tough story without a lot of real journalism experience — the combination of those things was a lot to handle. We did so, so much prep, but I think, in hindsight, we were maybe a little in over our heads. While that trip to Cameroon was one of the most challenging trips I’ve taken, it was also one of the most rewarding. I grew so much as a person, and as a journalist from it. Sometimes a little discomfort is the best way to learn and grow.”

In 2011, a recruiter from The Los Angeles Times saw Stevens’ work in Cameroon and offered him a job as an intern sports writer. Soon after, he was admitted into the paper’s Metpro fellowship program, which was created to launch the careers of recent college graduates from diverse backgrounds.

Interviewing a subject

On one of his first assignments as a Metpro reporter, trainees like Stevens were sent to different neighborhoods in search of a story. In Redondo Beach, Stevens heard about a man called Turkey Jon.

Each morning, Turkey Jon, whose real name is Jon Burt, cruised along Hermosa Avenue on his early morning, hour-long bike ride as the sleepy community was just opening its eyes.

Thanks to his diligent interviews, Stevens writes in “Turkey Jon, the rumpled mascot of Hermosa Beach” how the manager of Burt’s favorite restaurant, Good Stuff, poured apple juice, Coke, and water, and made a plate of tamales, which were not offered on the restaurant’s menu, for Burt’s arrival. Store associates and passersby all welcomed and greeted Burt. Stevens wrote:

“It doesn’t take much to win Burt’s affection, and when you do, it shows. Sitting on a bench at the end of the pier, he is quick to wrap his arm around you, adding pressure as he says something important. Later, squeezed together on the same side of a restaurant booth made for one, he asks a friend to scoot even closer.”

Burt, the son of a former city council member, had a mental disability from birth. Those who lived in Hermosa long enough to remember the once cozy, intimate community, looked after John. Wherever he biked, he enlivened the lives of those behind him.

“It’s that type of story that you do end up being very proud of,” Stevens said. “The people that were around Jon were very happy to talk about [him].”

After the story was published, Stevens said Burt would often call, looking for a friend to speak to. In an industry with multitudes of interviews and stories, to avoid being stretched too thin, Stevens said he had to learn when to let go of someone after their story was told. He asked himself, “How long should you continue this relationship? How much do you want to invest in this?” Stevens had to let Burt go.

A year ago, Burt passed away.

“I was sad to see that, but it felt like [my story] made a positive impact on his life: to see himself on the front page of the LA Times,” Stevens said. “And it also was something that the community was very proud of.”

Stevens was no longer pursuing a story that presented the most benefits to himself, like getting to enjoy a basketball game. At The LA Times, he had created a piece beyond himself and strayed far from sports writing; he never went back.

Editing a story

As Stevens reviewed the edits spanning the length of the story of his life, his eyes settled on the comment highlighting the word: home, “What does this mean? Clarify.” Growing up in an all-white family in the San Diego suburbs, the United States has been all he’s known.

In 2013, Stevens found himself on an assignment for The Los Angeles Times in Seoul, South Korea — his birthplace.

He had never met his birth parents before nor did he have any intention to; content with his childhood, he never — until now — explored his would-be life in Korea.

On this assignment, however, when he first saw his mother, and as she held him, she sobbed as he too broke down into tears.

“[My mom] was needing a lot of forgiveness, and I don’t think I realized that meeting with her would be as helpful to her and as comforting to her as it was,” Stevens said. “The impact of that whole sequence on me, journalistically, was not as much about meeting my biological mother and how that influenced things. I think that was another important step in my life journey toward becoming a little bit more Asian American or feeling a little bit more Korean.”

As a member of the Asian American Journalists Association, from then on, Stevens used this enthusiasm to strive to explore his identity and culture, while uplifting Asian American voices.

A recruiter at The New York Times, Dana Canedy, who had recently lost her husband in the Iraq War, resonated with Stevens’ story of adoption, and his mother’s struggle with single motherhood.

In April 2017, after four years of talking to recruiters and of interviews he flew to New York for with no responses, Stevens received a call with an offer to join The New York Times; soon after, he took a graveyard 5 p.m. to 1 a.m. shift in New York City.

While covering breaking news, Stevens was stoked by making impulse decisions and finding lucky breakthroughs. In one instance, when covering sexual harassment allegations against Wayne Pacelle, the C.E.O. of the Humane Society, Stevens was met by a stone wall of executives, who refused to budge in accepting his cold calls.

people called for the chief executive’s resignation. When covering this, Stevens was met by a stone wall of executives, who refused to budge in accepting his cold calls.

On Feb. 1, 2018, at 11 p.m., he struck gold. He was able to keep the caller on the phone long enough to build a rapport with her. Stevens learned Board Member Erika Brunson lived in familiar Beverly Grove, they both shared a favorite restaurant in her neighborhood, and she soon let a derogatory comment slip about the executive in question.

After, the executive director resigned and following the published interview, she did too. Stevens said he was proud that this stranger had felt he was somebody she could confide in.

Soon, Stevens learned that this skill could not just be used to catch incongruencies in a story, but to also comfort a grieving soul.

In 2018, Hurricane Michael ravaged parts of Florida with wind speeds of up to 162 miles per hour. One father had dropped off his kids at their grandparents’ modular home. As the rotating winds picked up, a carport was thrust into the home, killing his 11-year-old daughter.

What meant most to Stevens was that he could be there in the father’s distress to empathize with him, gain his trust, and express his immense sadness and story with fidelity.

But while doing so, Stevens also had to protect himself.

“I think that I have developed a certain out-of-body experience where I’m putting on my reporter hat and acting as a reporter but not letting myself feel at a certain level what is happening,” Stevens said.

He creates a barrier between him and the subjects of his stories to systematically conduct his interviews yet also be able to empathize without internalizing what he hears and “wallowing in sadness and self-pity.”

“I think different reporters deal with and do their human reporting in different ways,” Stevens said. “Some people put up boundaries and barriers on purpose just to make sure that they protect themselves. Other people dive straight in, all the way [with] both feet, and I think that is helpful and reflective in their writing, but also can be a big burden to carry.”

Reflecting on a story

“As [journalists] get older, we learn more rules and we have things that are assigned to us and we lose our [personal] voice to sort of fit an institutional voice,” Stevens said. “I still think that some of the best stories I ever wrote, I wrote when I was in college.”

Although there will always be a new beat to chase or a story to write, the constraints of writing for a big publication can be taxing on Stevens’ creative freedom. Despite this, the methodical craft he has developed is applicable to any beat, or what he reports on, that he occupies.

“I certainly think [that] I have put in 10,000 hours, by this point, of reporting and writing,” he said. “I still think of journalism very much as a craft like being a blacksmith or, or something in that area where we just do the same thing over and over again. I’ve probably written like 1,000, maybe 2,000 newspaper stories by this point. And so you just keep chipping away at getting better at all parts of this.”

After two years of covering the 2020 campaign trail, Stevens hypothesized that as a reward, his boss encouraged him to switch beats to arts and culture in Dec. 2020.

If he ever exhausts the depths of this topic, his company allows him flexibility in his beat. However, if and when the more than 1,600 newsroom jobs at The New York Times finally tire him, he’ll put 10,000 hours into standing at a new desk — Wenger’s desk — topped with assorted Beanie Babies, each with their own story, in a room with walls lined with newspapers. The California burrito, blue skies, the cool breeze, and the palm trees of San Diego will remind him of fond memories from high school.