Students should expand lexicons, verbalize eloquently

May 5, 2023

If you were asked to define your life from start to finish in 800 words—your wildest dream to worst nightmares, personal philosophy to political affiliation—you’d probably ask for more words. If asked, then, to describe not just yourself, but everything—and I mean everything—the Big Bang, dinosaurs, the cracks in the sidewalk and the eye color of one very kind person you met on public transport years ago—in the same 800 words, you’d gawk. You’d clarify, “800 for everything, everywhere, ever?” You’d ask for more. You’d need more. And you’re right–you do.

We all need language. It is an essential aspect of our existence. As billions of independent beings who can’t sync our consciousnesses, who can’t physically feel each other’s pains or joys, and who sometimes can’t even understand ourselves, our language provides a definitive labeling system for the everything and everywhere that we can’t fit into words so minimal as 800. Each word we know is a speck of the universe we can pin down, can put a name to.

Over the course of our brief centuries here on this Earth, we’ve realized the power of these words. We’ve honed them and sharpened our tongues, our wits, our spoken colors. We’ve thrown some around like spears and wrapped others up with them. We have conceived words for veritably all that can be perceived by human senses, and even more words for the unperceived forces that come from deep within or from far beyond. If it is, there’s probably a word for it.

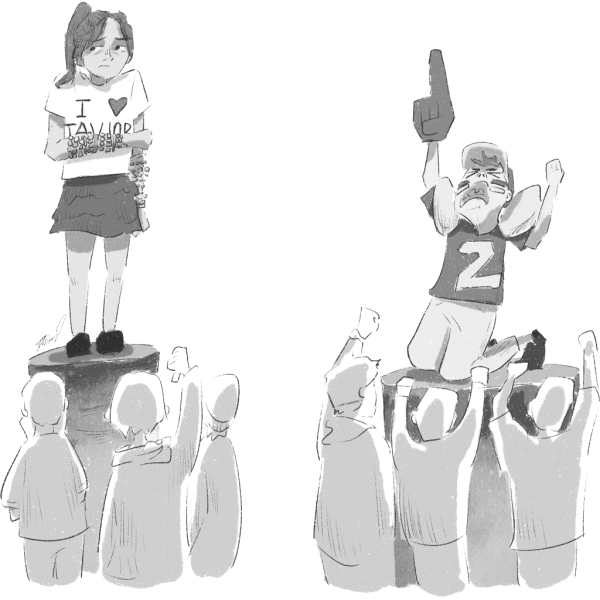

We are not at all restricted to a vocabulary bank, but as of late, we are restricted in our vocabulary bank. Jean Gross, advisor to the UK government on children’s speech, estimates that teenagers, on average, use 800 different words in their day-to-day lives. That’s a word bank shorter than this article. Much of our descriptions are littered with “like” and “very.”

We have somehow, instead of cherishing and growing language, run the great sands of world dialects through sieves and let the gold pass through while keeping insipid concrete debris.

As of 2023, the Oxford English dictionary states that aside from 171,476 words in current use, English has 47,156 obsolete words. Among their ranks are groak, which is of Scottish origin and means “to stare at someone whilst they are eating, as a dog might, in hopes that they will offer you some of their food,” and balatron, a “buffoon; one who speaks a lot of nonsense and is characterized by self-indulgence.” There’s even balter, “to dance poorly and clumsily, but with much enjoyment.” These words should be just the beginning of a more nuanced world, but they’re quickly becoming the end, the last soldiers standing.

Why are we shrinking our lexicons? The world hasn’t gotten any less interesting, that’s for sure.

These words are worth using. They’re precise, diverse, and so much zingier than vague roundabout descriptions. If we set our minds to the whetstone, we can wield our full arsenal against the army of misapprehension. No more “wdym” and no more having our intentions lost in limbo. Each of us stands to gain a great deal by communicating exactly what we mean, and we have the perfect tools at our fingertips: the nearly quarter of a million words that we neglect to use each day.

What happens to us when we can’t definitively convey anything, even to ourselves? Look no further than 1984’s Newspeak enabling the reign of Big Brother. Perhaps even worse is exulansis. We give up on sharing our experiences, observations, feelings, and thoughts, because no one can seem to relate to them; and, in shutting these experiences out, drifting away from them until we are just as dissociated from them as everyone else. We bubble and brew in perpetual adronitis. Hours of sleep lost to catoptric tristesse. The intricate spider web of humanity that is language, our only tether to each other, ourselves, and the past in a void of conscious onism is severed. We have these words, these threads, but when we don’t take care to know or use them, we may as well say nothing at all.

An embrace of souls becomes a limp and clammy handshake, an arrow to the heart becomes a shot in the dark, and the relief of knowing you are known is replaced by futile hope, deep down, that someone somehow read your mind line for line, but knowing even deeper down that they probably didn’t. Every human’s life is inimitable, but to throw ambiguous pebbles of “you know” and “I’m not quite sure how to explain it, but something like that” at the windows of each other’s souls, waiting for them to hear us and open up, when we have 218,632 words at our disposal, would be very, very bad.