Romanticizing Criminals in the Media

September 16, 2022

In the midst of another late-night search for good web novels and comics, I came across a psychological-thriller-horror-romance story. Among this handful of genres, the word romance seems out of place. A mistake, perhaps? One would presume so, but with my experience in the field of random, unhinged stories on the Internet, I knew all too well it was intentionally and thoughtfully placed. And of course, at 4:30 a.m. on a Monday, in my fever dream state, I decided to binge all 56 chapters.

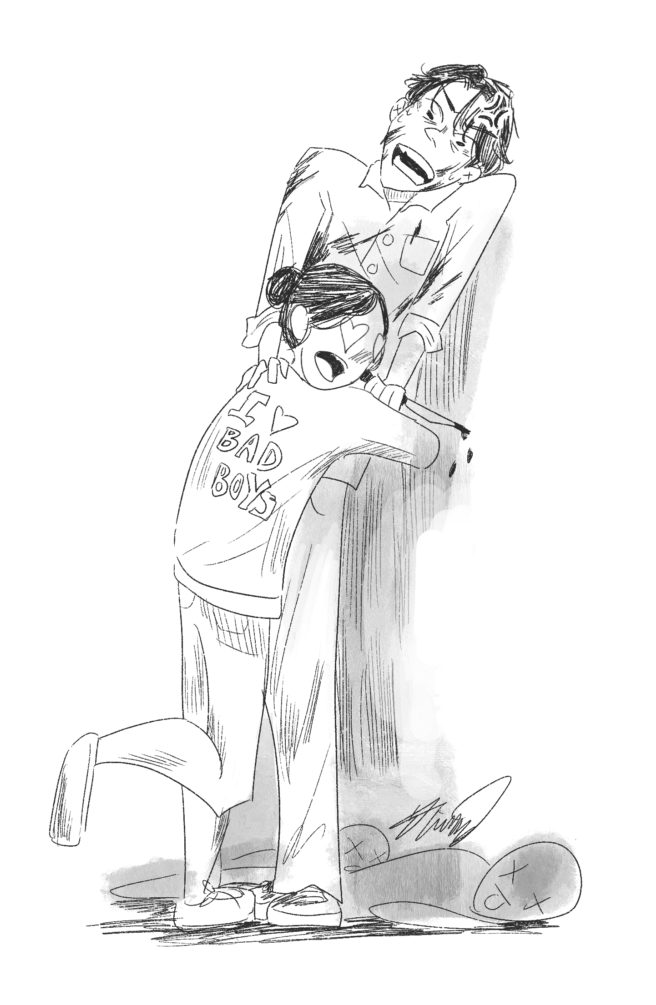

The story was complex, to put it lightly. The plot involved a stalker and a victim, held hostage in their own home, and the unwanted development of their relationship. And, in the end, the victim’s eventual psychological breakdown into falling in love with their predator. The story was an example of Stockholm syndrome and the horror of its effects. They didn’t want to show a bubbly romance story, but moreover, the psychology of a deranged love borne out of manipulation.

What makes the story complex though was not so much the storyline, being straightforward in its message, but the readers’ responses to it. The comments at the beginning say how utterly disgusted and repulsed the readers are with the stalker and his actions. But after a certain point in the story, when the stalker had revealed his face, the comment section began to change their attitudes. Comments like “I forgive him because he’s hot,” “I’m falling in love,” “Victim’s name is so lucky,” and last but certainly not least, “I wish he would have chosen me instead.” The readers even began to bring up the stalker’s tragic backstory, which they had promptly disregarded before he revealed his face, to justify for he had done.

In my voyage of the questionable online world, I have seen many comments like these for various kinds of characters—kidnappers, murderers, arsonists—in essence, people who do horrific things but who are conventionally attractive. And, honestly and regrettably, I have come to find these responses to be “normal.”

But, at 6:27 a.m. on that Monday morning, I had a moment of clarity. How is this normal? Falling in love with criminals, saying victims are lucky, forgiving people for their inhumane actions, defending them, and asking, even jokingly, to be kidnapped or murdered—all because someone is attractive? Most of all, how have I failed to notice how messed up this is?

Appalled by this epiphany, I went to my friends to discuss my new discovery. It was there that certain characters were brought up, such as the Darkling from Shadow and Bone, Hannibal Lector from NBC’s Hannibal, and Jang Jun Woo from Vincenzo, that my friends and I figured out we were just as guilty of this phenomenon. Comments such as “but, that’s different,” “they feel bad about what they did,” “he has reasons,” and even “he’s attractive,” were said. We were shocked at how easily we could defend such characters and provide excuses for their actions.

These kinds of comments have become so widespread and normalized that no one blinks twice from hearing or even speaking these ideas themselves, including myself. Think about certain sounds on TikTok, Instagram edits of good-looking villains, or Youtube videos justifying countless amounts of crimes because of “tragic backstories”. But, there are none for unattractive characters with the exact same motives. This phenomenon of pretty privilege does exist, in real life as well, and it has become so extreme to the point that writers have begun to purposely make these kinds of characters. And, in a series of cause and effect, we begin to accept fangirling over them as normal. We justify it by the characters being fictional, but these types of comments still set a culture of desensitizing criminals, which in small ways can translate into real life.

In any kind of media, whether it be comics, web novels, TV shows, k-dramas, or animes—attractive characters who do awful things are loved by viewers. We defend them without a second thought, not realizing how disturbing this kind of looks-first culture is. In reality, we separate ourselves from fans of Ted Bundy, who gush about how attractive he is, but how are we that different? Sure, these characters aren’t real. But, we say the same things without realizing the severity of our words, and it sets a precedent of desensitizing and romanticizing criminals, fictional or not. We all have to take a step back to witness how unsettling this part of our culture is, and I hope, in that, we can take into account the weight of our words a little bit more.

Anastasia • May 1, 2023 at 5:37 am

Some of my favorite characters are villains, but I would never justify their actions only because they are cute or because of their backstory. There’s nothing wrong with liking villains, but the type of comments you’ve talked about are stupid and disgusting. This phenomenom is called woobifycation and it’s extremely annoying.