Staff grapples with excess instructional minutes

June 2, 2023

Due to an excess of approximately 1,311 instructional minutes, Westview has accumulated this past school year, we will be having minimum days on Monday and Tuesday.

Annually, California high schools are required to have 64,800 instructional minutes per school year and Westview’s plan with these instructional minutes had been carefully planned at the start of the school year. Art teacher Keith Opstad said that Westview’s bell schedule is an ideal model for maximizing instructional minutes.

are required to have 64,800 instructional minutes per school year and Westview’s plan with these instructional minutes had been carefully planned at the start of the school year. Art teacher Keith Opstad said that Westview’s bell schedule is an ideal model for maximizing instructional minutes.

The term ‘instructional minutes’ is not synonymous with time teachers spend instructing in front of a class. Rather, Wolverine Time, SSH, Homeroom, and some passing periods also count as instructional minutes, as long as they fall within the school day. If these breaks were directly before fourth period or on either side of lunch, they would not be counted in instructional minutes.

Plus, other high schools have a 10-15 minute nutrition break in the morning, which is not counted as instructional time, but this break is built into Westview’s Wolverine Time. Scheduling details like these are part of what caused the disparity between Westview and other PUSD high school’s instructional minutes.

On top of this, Poway Unified requires each school in the district to build in a buffer of 500 extra instructional minutes per school year to ensure that schools are surpassing the district’s bare minimum requirements to ensure schools have a buffer in case of emergencies such as natural disasters.

“An example of why [we have a buffer] is when Rancho Bernardo and Bernardo Heights’ air conditioners broke down in September when the heat was extremely high and we had to call for minimum days at those schools,” Learning Support Services (LSS) Superintendent Carol Osborne said. “Bernardo Heights had extra instructional minutes so that was allowable, but Rancho Bernardo did not have enough instructional minutes so we had to apply for a waiver with the California Department of Education because they would not be meeting the minimum required instructions this year.”

For high schools particularly, having an excess of instructional minutes also allows schools to modify the schedules on days of term changes, AP or state testing, and even schoolwide rallies.

“Any days with unique reduced schedules need to be planned ahead, which can happen with extra instructional minutes,” Osborne said.

In response to the 1,300-minute excess of instructional minutes, Opstad decided to send a survey to Westview students, teachers, and staff members about what changes they would like to see in scheduling.

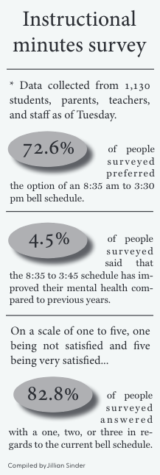

In his survey, Opstad received 1,130 responses as of Tuesday. Of these responses, 87.5% are from students, 7.6% are from teachers, and the remaining 4.9% come from staff, administrators, and parents.

Only 4.5% agreed with the statement that the 2023-2024 bell schedule has improved their mental health and 56% of all those surveyed stated that their ideal bell schedule out of the given options in the survey would be to start school at 8:35 am and end classes at 3:35 pm.

“The data was overwhelming that the entire Westview community wanted to get out earlier and would be interested in using some of that banked time,” Opstad said.

After collecting data, Opstad then shared the results with Poway Federation of Teachers (PFT) and the Executive Director of LSS and requested a meeting to brainstorm solutions to minimizing future instructional minutes.

“I pitched the idea that we have so many instructional minutes we could possibly get out earlier,” Opstad said. “At that point, the non-negotiable was that we can’t start before 8:35, but I was told that if we had an excess of instructional minutes, we could possibly bank them and we could have some extra minimum days.”

However, according to Osborne, surveys need to be made by LSS and in collaboration with PFT in order to have effect on instituting district-level changes, such as schedule alterations. Additionally, she said that it is important that surveys do not make offers, such as the minimum day offer in Opstad’s survey, before these offers have been confirmed.

“[The district] works with PFT to jointly create surveys for students, parents and teachers to make sure that we’re able to offer what we are asking in our questions. We don’t want to mislead anyone about what we can provide.”

Plus, according to Osborne, transportation is a key element when it comes to adding minimum days. In order to approve the change in the busing schedule, both parents and transportation needs a 30-day notice to plan ahead. Transportation constraints are also relevant when it comes to adjusting the schedule for next year. “We would need more buses and more drivers to be able to have greater flexibility with schedules, and that would all require funding,” Osborne said. “The board made a decision [on our current schedule] that was fiscally responsible and had less impact on the number of buses required. We have to anchor our decisions in what we’re really able to do, what’s fiscally responsible, and what’s sustainable for Poway Unified. We’re making do with the number of buses that we have in our fleet and the existing drivers are often working more than one shift in some cases.”

With this in mind, Opstad found out how many students have bus passes. In the morning, there are 205 students with bus passes, equating to 9% of the student population, and in the afternoon, there are 150, equating to 6% of the student population. But, Opstad says that this number doesn’t necessarily dictate how many students actually ride the bus.

“That [number] is just bus passes,” Opstad siad. “So, a couple of teachers have been checking to see how many students are actually taking the bus after school, and it’s a fraction. Students get their licenses later on, maybe they have spring sports but even though we have 150 of those bus passes, not 150 people are on the bus every single day.”

Nevertheless, Spanish teacher and one of Westview’s union representatives, Andrea Ford said that she sees the impact of Westview’s longer days in her students.

“I feel like I’m seeing more burnout than normal,” Ford said. “I feel like students are just done. You can tell students are tired, they’re talking about how much work they have and how bogged down they are.”

For Ford, the most important thing is advocating for the students and, while she said that the minimum days only gained back a fraction of the excess instructional minutes, she is hopeful that it is a signal that positive changes are being made.

“One thing that Westview’s really good at is pushing for kids and pushing for the majority of the student voice and what’s best for [the students],” Ford said. “What’s at the root of everything is we see how this is impacting education. There’s nothing we can do about the [later start time]; that’s a law. But, we can end earlier by dispersing those instructional minutes differently during the day.”

Opstad also said he is hopeful for how the schedule may change next year and looks forward to the decision-making process being inclusive and a collaborative effort.

“You can’t really change the past, but you can change things moving forward, and if you do it in an intelligent way that is data-driven, that is transparent, that is inclusive, it’s pretty hard to challenge,” Opstad said. “I’m hoping that we still can get out a little bit earlier for next year and then we’ll make an educated decision, gather more data, and continue to improve. I never teach the same thing in my classroom; I’m always trying to change, make it more relevant, make it more inclusive, make it more diverse. If we need to change our schedule or different policies at Westview, I don’t want it to be one person making the decision; I want it to be a group decision because I really do believe that there is a Westview community and everyone’s opinion matters.”