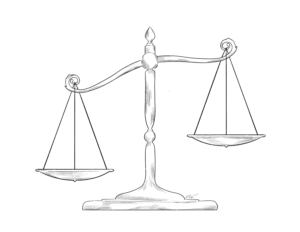

Legal Lapses: Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools

March 17, 2023

For the 12 years he attended school within the Sturgis Public School District, Miguel Perez was lied to.

The school district knew that he required instruction in American Sign Language (ASL), but Perez’s classroom aide’s sole qualification was that she “attempted to teach herself Signed English by reading a book.” Perez’s family was lied to about their son’s untrained and unqualified classroom aide, who abandoned Perez for hours at a time, leaving him with no method of communication. They were lied to about the ‘signed English’ Perez was taught– a non-existent language in reality. They were even lied to about his progress when Sturgis inflated Perez’s grades, misrepresenting what he had truly learned.

In December 2017, Perez’s lawyers filed a due process claim with the Michigan Department of Education that the district had violated the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Rehabilitation Act, and two Michigan laws.

The IDEA ensures students with a disability have a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). An Individualized Education Program, or IEP, is one of the elements outlined in the IDEA. On the other hand, the ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits disability-based discrimination.

Prior to the due process hearing, the district gave Perez a settlement offer. This offer would place Perez in the Michigan School for the Deaf as well as pay for his post-secondary compensatory education, sign language instruction for both Perez and his family, and the attorney fees in the case. Perez accepted the settlement.

Although the settlement agreement did not pertain to Perez’s ADA claim, when Perez filed an ADA claim in the federal district court, the district court dismissed his claim. Through the ADA claim, Perez specifically sought money damages as compensation to address his lost income and emotional distress among other harms.

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the ADA claim as well, affirming the district court’s judgment.

Perez appealed and the case is now before the U.S, Supreme Court.

Marc Charmatz is one of the attorneys who worked on Perez’s brief before the Supreme Court. Charmatz is also a senior attorney and the longest-serving staff member at the National Association for the Deaf. Throughout his 46-year career, Charmatz has specialized in cases with deaf individuals.

“Before the due process hearing, the parents and school district can settle the case under the IDEA,” Charmatz said. “Almost every judge will tell you that settlements are good because it takes that case off their plate.”

The district court ruled that Perez could not bring his ADA claim because he had settled and didn’t exhaust administrative remedies, a requirement in Section 1415(l) of the IDEA.

Exhausting administrative remedies would entail pursuing them to “an appropriate conclusion”. However, Section 1415(l) specifically states that exhaustion is required only when the relief one is seeking is available under the IDEA’s subchapters.

“There’s almost universal agreement that the ADA’s compensatory damages are not available with the IDEA,” Charmatz said. “If you can’t get money under the IDEA and you’re suing only for money, you should be able to move ahead. That’s one of the strong arguments.”

Yet, even if there is an exhaustion requirement, the petitioners argue that settlement should constitute exhaustion.

“The whole purpose of the IDEA was to be more collaborative and to work together to resolve [issues],” Charmatz said. “That’s why we have mediation. If settlement didn’t constitute exhaustion of administrative remedies, you’d make everyone go to a hearing. It’s expensive and it’s time-consuming.”

Ultimately, ruling in favor of the school district would set a dangerous precedent: families and students would be forced to reject a favorable settlement in order to even bring an ADA claim to court.

The same IDEA section with the exhaustion requirement ironically also states “Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to restrict or limit the rights … available under the Constitution, the American with Disabilities Act … or other federal laws protecting the rights of children with disabilities.”

The Supreme Court must uphold and protect the rights of individuals with disabilities under both the ADA and IDEA as they were clearly intended to.