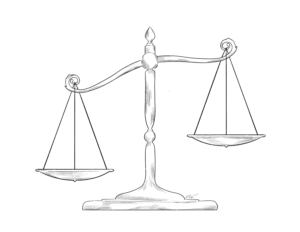

Legal Lapses: National Pork Producers Council v. Ross

November 18, 2022

In 2018, California passed Proposition 12, the Prevention of Cruelty to Farm Animals Act. The proposition established requirements for farmers to provide a minimum amount of space for egg-laying hens, breeding pigs, and calves raised for veal. This would apply to eggs and pork sold in California as well as the state where it was produced. If farmers didn’t meet that requirement, businesses would be banned from selling such products.

Proposition 12 was intended to improve California’s Proposition 2. Passed in 2008, Proposition 2 banned battery cages and gestation crates—both of which greatly restrict an animal’s mobility and often result in stress, frustration, and trauma for the animals. Despite this, pork producers continue to be proponents for gestation crates as they maximize the number of animals housed in a single area, reduce labor costs, and prevent injury from the sows being aggressive towards each other.

Unsurprisingly, the pork industry has attempted to block the implementation of Proposition 12. In 2021, the Supreme Court rejected a lawsuit from the North American Meat Institute to block the proposition. On Jan. 1, 2022, Proposition 12 went into effect.

Now, Proposition 12 is once again being scrutinized. The National Pork Producers Council sued Karen Ross, the Secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture under the Dormant Commerce Clause, which prohibits states from “passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce.”

The council argued that requiring farmers to comply with California requirements in Proposition 12 places an undue burden on interstate commerce as approximately 87% of the pork sold in-state comes from producers outside of California.

Both the district court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals had dismissed the lawsuit. Thus, the National Pork Producers Council filed a writ of certiorari, or a request for the Supreme Court to hear the case.

The writ was granted.

Although the case is concerning a specific industry, its ruling is likely to have widespread implications.

For example, during oral arguments, Justice Elena Kagan pointed out how interstate disputes could be exacerbated through policy. California could implement laws requiring products to be manufactured using union labor, while Texas could implement a law prohibiting the use of union labor.

The attorneys for respondent Ross argued that the case would not impact policy as it’s “focused on the production of goods” and not the company’s policy itself.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh pushed back, challenging the permissibility of a hypothetical law that would prohibit selling fruit produced by undocumented immigrants. Similarly to Kavanaugh and Kagan, Justice Amy Coney Barrett questioned whether states could prohibit selling goods produced by unvaccinated workers.

Although the decision is likely to be released next June, the case is reflective of increasing polarization and divisiveness in the United States. States imposing their political or moral views on others through economic means is a frightening possibility in today’s political climate, one that has shown time and time again that chances for compromise and unity are slim.