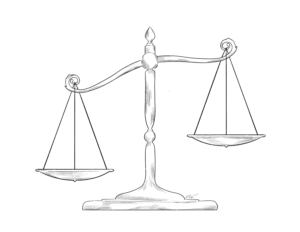

Legal Lapses: Johnson v. Arteaga-Martinez

August 26, 2022

Antonio Arteaga-Martinez is a Mexican citizen. First arriving in the United States in 2001, Martinez had gone back to Mexico a decade later only to be beaten by a street gang, prompting his return to the United States. He wasn’t a criminal, but he had committed a crime: the crime of entering the United States. While detained, he sought the right to asylum. His claim seeking asylum was found credible by an asylum officer, yet he remained detained.

After four months of detention, Arteaga-Martinez challenged his detention without a bond-hearing.

Arteaga-Martinez is one of the thousands of cases exemplifying the inhumane treatment of asylum-seekers in the United States. A report published by Human Rights First found that ICE has held “tens of thousands of people in jails instead of allowing them to live in the US with their families or sponsors as their asylum cases are decided.” They furthered that jailing asylum seekers has subjected people to severe physical and psychological harm, as the practice is “inhumane, unnecessary, and wasteful.”

Generally, ICE or an immigration judge assigns a bond, or a certain amount of money that allows a person to be released from detention. In a bond hearing, one must prove that they are not a “flight risk,” and not a threat to national security to be granted the bond. In Arteaga-Martinez’s case, aside from minor traffic violations, he had no criminal history.

However, people often do not receive a bond determination from ICE at all, in which case a bond redetermination hearing may be requested.

The Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that Arteaga-Martinez did have the right to a bond hearing, and would have to be released after six months of detention unless the government found that he “posed a threat to the community.”

The Director of ICE, Tae Johnson, appealed the ruling, at which point the case reached the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts’ rulings, determining that immigrants held for deportation may be detained indefinitely, with no right to go free on bond.

The court, with a 8-1 majority, found that Section 1231(a)(6) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, which was cited by the lower courts, did not “even hint at the requirements imposed below [the requirement to provide bond hearings after six months of detention].”

According to 1231(a)(6), there is a 90-day removal period in which the government must ensure the removal of the individual from the United States. After the period expires, which it did in Arteaga-Martinez’s case, the statute states that the government “may detain only four categories of people,” with those categories referring to the risk the individual poses to the community and national security.

One of the central issues in the case was that the statute does not explicitly claim how long detention may occur past the 90-day period. In Zadvydas v. Davis, a 2001 case, the Supreme Court stated the indefinite detention of immigrants was impermissible, and held that the statute “limits post-removal-period detention to a period reasonably necessary.” That period was assumed by the court to be six months. But in the case Johnson v. Arteaga-Martinez, the 2001 precedent was reversed, stating “On its face, the statute says nothing about bond hearings before immigration judges… nor does it provide any other indication that such procedures are required.”

This case serves as a reminder of an unfortunately sour theme in rulings, ones that consistently deny rights based on the “lack-of.” A bond hearing is denied due to the lack of specificity in a law.

But the precedent this case sets for immigration law is undeniable. According to the ACLU, denying bond hearings can have life-threatening consequences due to ICE’s record of abuse, neglect and death in detention centers.

This ruling opposes a country founded on the principle of a right to a fair trial without unnecessary delay, a country which should champion the Sixth amendment.