Why we read the books we do: A look into the required reading texts in our English courses

Each year, freshmen English students sit in class learning, for the first time, the dreams of Lennie and George and the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet. Simultaneously, sophomores experience the delirium of Lady Macbeth, juniors analyze the yearning of Gatsby, and seniors feel the watchful gaze of Big Brother. Reading these novels in high school feels like clockwork: students’ older siblings—and maybe even their parents—likely read the same Stienbeck and Shakespeare when they were in high school. These texts are so normalized in our high school curriculum that reading The Scarlet Letter seems to be as natural of an aspect of the Westview experience as the freshman triathlon or sophomore Unity Day.

On one hand, these texts are taught in our curriculum because they are “classics” or, as some put it, part of the “literary canon”—basically meaning that they have been around for long enough and acquired enough acclaim to merit the weeks of analysis that high school students devote. Yet, there are many “classic” books out there, so why do we read these particular classics?

The answer comes partly from the “Core Literature” list, which includes the books that have been district-approved for teaching at a given grade level. The list holds many titles that will be familiar to students, with Animal Farm designated to freshmen and East of Eden to juniors. In order for a teacher to assign a book from this list as required reading, Westview simply has to acquire enough copies of the text. According to library media teacher Cheri Tomboc-Brownlie, the list is designated by grade level so any students who remain in PUSD for years K-12 are not being taught Of Mice and Men twice, for example.

The books are decided based on content, reading level, and, most significant for high school students, curriculum for each grade level. For 11th grade, for example, the list contains mostly American writers as classes like American Literature and U.S. History are part of the junior year curriculum. Learning Support Services (LSS) oversees this list and any changes made, as well as overseeing all of the PUSD curriculum. No LSS employees who I spoke to know when the list originated, though previous LSS Director Eric Lehew said the list was already around when he joined the district in 1982.

Student activism groups like Diversify Our Narrative PUSD assert that the books taught in school need to change, that the texts must be more representative of various cultures and backgrounds. The group has been meeting with district officials and English teachers about the changes they think are necessary to our reading lists. President Madison McGuire (12) said she believes that introducing more perspectives of people of color in our assigned reading is necessary.

“As [high school students] are forming themselves into the people they want to be, it is incredibly essential for students of color to see themselves as the main character, to see that they can own the spotlight, that their story is just as important,” McGuire said.

Though this hasn’t occurred since the ’90s, big additions or changes to the Core Literature list can be made when a committee of English teachers from all grade levels across PUSD meet to discuss and agree upon the changes.

Tomboc-Brownlie, who has attended some of these meetings, said they can get pretty “contentious” because English teachers are so passionate about what they teach. Expository Writing and World Literature teacher Jim Jennings said that often, with so many varying opinions in the meetings, the results can be disappointing.

“All the English teachers got together in the mid-90s probably, to decide on new books to teach,” Jennings said. “Once we started filtering through all the books that teachers wanted to teach, the books that made the cut were A River Sutra, A Place Where the Sea Remembers, and Bean Trees [for senior English]. And at the end of the day, most teachers weren’t excited about teaching those books. Imagine going through all that work and then not teaching Bean Trees because my students have told me that they don’t like it.”

Based on student and teacher concerns with the titles taught in classrooms, LSS has been planning to make changes to the Core Literature list. During the 2019-2020 school year, Director Beth Perisic said she met with English department chairs across the district to discuss the list.

“We talked about things like: Do we even need a Core list anymore?” Perisic said. “What is it that we’re trying to accomplish with students and their reading in English class? How does it tie into the standards that we have that we know we need to teach? It was a great conversation. I know the [department chairs] took the conversation back to the teachers in their departments and [the English teachers] are considering and thinking about new titles to offer.”

Real changes to the Core Literature list, however, cannot be made until the district has the funding to adopt new books, as they can only afford a finite number of new textbooks each year.

“We want to make sure that if we engage in this work, we have the funding to purchase the new titles,” Perisic said. “Certainly, looking at Core Literature is on our list of priorities, but we also have priorities around adopting new history books right now. Middle schools and high schools still need to do that work [in adopting new history books].”

Though the Core Literature list hasn’t changed in many years, teachers can still decide exactly what books from this list they want to teach in their classrooms. Jennings said he chooses to teach books that he has a personal connection with and books with universal messages that he thinks students will benefit from.

“I just really love satire,” Jennings said. “ When dystopian novels became really popular for kids, 1984 and Brave New World held up as books that students were interested in, and they would tell me that at the end of the year. And still, I love teaching them—if I had to teach only one book, it would be 1984. The themes are important. It gets students to question authority and is important, especially today for students to understand as events like Donald Trump being pulled off Twitter are described as Orwellian.”

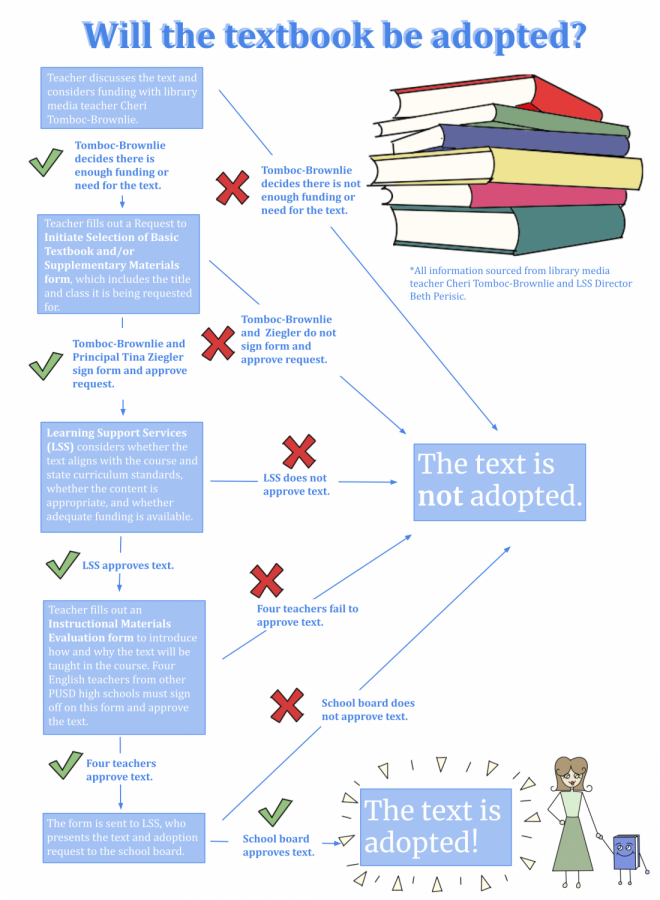

If teachers want to teach a novel that isn’t on the Core Literature list, they can also go through the textbook adoption process. According to the Board Textbook Adoption Policy—“textbooks” meaning the word in its common use alongside literary works or literary selections—new books can be adopted to provide a more complete coverage of a topic, the meeting of various learning ability needs, the meeting of educational needs of students with language disabilities, or the meeting of diverse educational needs of students reflective of a condition of cultural pluralism, according to the policy.

In order for a teacher to adopt a new text, it must be first approved by the school librarian and principal based on whether our site has the funding necessary to purchase adequate copies of the text. Then they send their request to LSS.

According to Perisic, LSS helps facilitate the adoption of new texts by reviewing content for younger students, reviewing whether the way the text will be taught aligns with course and state content standards, and reviewing whether there is adequate funding to adopt these texts.

After receiving LSS approval, the text needs to be approved by English teachers at the four other PUSD high schools based on criteria like whether it fits the curriculum and has “significant educational, social, or artistic value.”

After this, LSS presents the request to the school board. Once the school board approves the text, school sites may purchase copies of the text.

This process can often take many months or longer, which is why Honors Humanities and AP Literature teacher Bob McHeffey said it’s easier to tailor the English curriculum to the books we already have rather than introduce new ones.

“If you’re teaching Of Mice and Men, which is really about tramps in the Depression, which really doesn’t matter to a whole lot of our students, we ask ourselves, ‘Can we turn this into something on immigration or something about the treatment of people with various mental capabilities?’” McHeffey said. “So, we tailor the teaching [of the books on the protected list] to the interests of the students or the aspects that are applicable in a modern context rather than adopting a new text because it can take years, and it’s hard.”

Jennings said he finds himself in this situation, yet, like McHeffey, because he enjoys teaching many of the books on the protected list, he doesn’t believe that this changes the quality of learning for his students.

“There isn’t a book that’s not on the protected list that I’m passionate enough about to drop everything and go through the whole process of getting it adopted,” Jennings said. “I think most of us [English teachers] look at all the hoops we have to jump through and think, ‘All right, I’ll just teach To Kill a Mockingbird.’ If I truly couldn’t teach any of the books [on the protected list] with passion, then I would probably go through the process. But I am passionate about the books on the list—I haven’t taught freshmen in 10 years and I could still quote To Kill a Mockingbird. ”

Many students said they have benefitted from the books taught in English courses. Diya Sharma (12) said that the books she was taught in high school were “diverse and amazing.” According to Jayden Xia (11), the selection of books he was taught freshman year were “generally uninteresting” yet have helped him in learning the skills needed for future English courses.

“For example, I think that the analysis on To Kill A Mockingbird was generally repetitive and lacking in potential for any new insights, but coupling it with teacher lectures, peer review, and actually analyzing it myself helped me to get a grasp on what literary analysis was,” Xia said.

Other students say that the selection of texts in English courses is lacking in diversity, Sophia Chiu (12) being one of them. Chiu said that she did enjoy many of the books she read in English classes, but the fact that most of the books she read were from “white male authors of the same time period” made her English experience more negative.

“As much as I respect a lot of the classics (they’re classics for a reason) and I do agree that they touch upon universal themes, which anyone can experience, I’ve always felt a disconnect between myself and the characters, as an Asian-American woman, because it sends this message that you can only fully express yourself or even have these profound, intellectual thoughts if you are white, male, etc.” Chiu said. “The women are generally hyper-sexualized and condemned by society or criticized for being unattractive to men, and Asians in these books are generally nonexistent.”

Though the majority of books on the protected list are written by white male authors, many teachers are still able to introduce different perspectives with the few “protected” books that are written by Black or Hispanic authors, for example. Jennings said he introduces diverse perspectives to his World Literature class by teaching the novel Things Fall Apart by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, which depicts the effects of imperialism on Nigeria.

“Students are familiar with imperialism, but usually the studies of it are through a European lens,” Jennings said. “When we see it from Achebe’s perspective, it opens up questions about behaviors and events that we see happening today. For students to hear a voice like Achebe is important in their education.”

Even beyond the Core Literature list, teachers can reap the benefits that more diverse literature can bring by having students read texts individually or in small groups, as any book that is read by less than 10 students doesn’t need to go through the adoption process for approval. For this reason, McHeffey allows both his Honors Humanities and AP Literature students to choose from a long list of novels to study individually or in small groups.

“I try to teach a variety of voices,” McHeffey said. “So, I want to vary not just across culture, but across topic, style, and time period. I try to get a wide variety so [students] can learn a breadth of things and in that I would hope that they could find something that clicks on a thematic level or on a personal level. That’s why I let my students read what works for them, rather than me deciding what works for them.”

AP Literature student Aaron Fan (12) said that the diverse range of perspectives, voices, and nationalities he chooses from in deciding what books to read for the class have greatly enriched his experience in English class.

“It’s interesting to see how people from different countries write differently and think differently,” Fan said. “You get to know the thought processes of people from other countries, you’re not limited to the American perspective from the ‘classic American novels,’ which expands your perspective. ”

The aspect of choice over what books are read in the class, Fan said, has helped him discover new interests in literature.

“It’s even better than, say, being forced to read books from other countries because you can choose to read what you are interested in and if you aren’t interested in one thing you can switch around,” Fan said. “You can find out what interests you. Personally, I’ve found that I’m really interested in Russian literature which I never would have found out without [choosing the books I read].”

Perisic said that LSS and English teachers across the district are looking into the value of student choice when it comes to the literature that is read in our English courses. In future conversations about the books taught in our English classes, Perisic said there will be consideration of the value of teaching the same book to an entire class versus letting students choose what texts they read.

“[The district] has moved towards standards that are not so discrete but are more skills-based, so we can teach those skills through a variety of different texts,” Perisic said. “We don’t all have to read the same thing. There has been no decision made about this, but it certainly is going to become part of the conversation.”

According to Associate Superintendent Carol Osborne, who oversees LSS, this idea would allow sites to buy a wider variety of texts, as they don’t have to buy as many copies. Still, Osborne said that making our literature more representative is a district priority.

“One of our goals is to ensure that our students see themselves in the texts that they read and can connect with them,” Osborne said. “And this relates with our focus on racial equity and inclusion, with the work that we’ve been doing around equity. The bottom line, I think, is that we want to make sure that the texts that we’re using with students are relevant and engaging, and help them to develop their critical thinking and knowledge of analysis of text and understanding of different perspectives, different from their own, as well as perspectives that they can relate to personally. And so it’s making sure that we are being student-centered and student-focused in the texts that we’re bringing into the classroom.”

![Kamila Nava (11) [right] and Alexi Stysis (11) run at Torrey Pines State Beach, April 27. Nava enjoys going for runs outdoors and tries to run in nature as frequently as possible.](https://wvnexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/DSCF2398-e1714686258569-400x600.jpg)