Singhai volunteers for youth crisis hotline

June 2, 2023

For the past few months, I’ve worked as a crisis counselor with the California Youth Crisis Line. In the 1,247 minutes I’ve actively been on call or chat, I’ve spoken to 25 people. Ten struggled with anxiety and depression. Six had suicidal ideations. Three were sexually assaulted, and three were abused as children.

But these individuals are more than a statistic. They have stories to share, experiences to process, and moments still to enjoy. One girl loved writing poetry. Another enjoyed math. Others turned to reading. I’m grateful to be there for them, even if it’s only for a few hours. But in that time, it’s become clear that many have undergone trauma that I wish no person ever had.

One young adult felt guilty for surviving a school shooting. She was frustrated that in the years since, nothing had changed: school shootings were still routinely occurring. I learned that she had channeled her pain into passion, into volunteering at organizations advocating for gun safety. But her suffering from her past made it difficult for her to see the strides she was making towards a safer future. I didn’t know her, but I felt for her, overwhelmingly so. I felt the anger and disappointment in her voice.

Nothing could have truly prepared me for this work. I realize now that no amount of reading and researching could allow me to understand the raw emotion the way I could while volunteering. But a year ago, all I knew was that I wanted to help.

Because two years ago, I didn’t know where to turn for help. After being diagnosed with an eating disorder, I was confused, scared, overwhelmed. At that point, I was spiraling. I was looking for an answer that did not exist, parsing emotions for a truth that I had not yet articulated. What I needed was to be heard. What I needed was to understand myself.

Eventually, I turned to my therapist, my parents and my friends. I tried to be patient with myself, taking the time to listen to my feelings. I recovered, but I wanted to give back the support I had received.

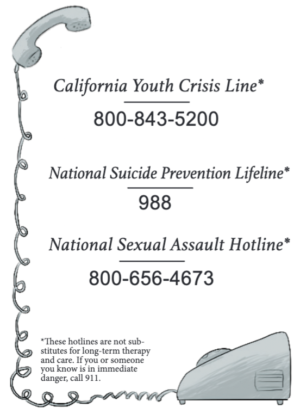

Although I didn’t have any personal experience with hotlines before volunteering, I applied to the California Youth Crisis Line in June of last year. I was subsequently interviewed and went through 50 hours of training.

Through training, I began to understand how to handle cases involving suicide, child abuse and human trafficking. An individual can define what crisis means to them, whether that’s struggles with a friend group or suicidal thoughts, and so the hotline welcomes everyone. Thus, it’s imperative for counselors to be able to respond to a broad range of crises.

We weren’t given a manual or taught what to say. We were taught how to think—not to compliment or reassure or pretend to empathize, because frankly we may never truly be able to— but to acknowledge and affirm our callers. I learned to say what I saw was true about them, whether that be their kindness or their dedication to helping themself. And I’ve found that there are some universal truths: there is always something about others that I can find inspiring, people have the capacity to arrive at their own answers, and everyone has goals and dreams and the ability to make a difference.

When I began taking calls, I naively wanted to problem-solve. I hoped that in some way, I could end someone else’s worries. But throughout my experiences, I’ve realized that sometimes there is no right answer, no cure to a disease, no home for a child—the truth I hate, I’ve tried to accept. Because sometimes, the only remedy is humanity, the intangible feeling of being seen, one that I presume many calling a crisis line are seeking.

The pre-teen girl who had been raped by her stepfather was appreciative when I merely told her I was there to support her, that I wanted to hear whatever parts of her story she was comfortable sharing. Nobody had ever told her that, she said.

Although I stayed online with her for nearly three hours that night, I’m completely unaware as to how she’s doing today. It’s been incredibly difficult, painful at times, to grapple with the fact that my capabilities as a crisis counselor are limited. I often wonder if the individuals I spoke to are okay. I wonder if the CPS reports I filed went anywhere. I wonder if the police dispatchers I talked to followed-up. There’s a tremendous sense of helplessness in knowing that there is nothing I can do to truly solve everything.

But I’ve found that there is comfort in the fact that I can leave each caller with a little more hope than they began with. I can listen. I can care. I can understand. I can show that I know how courageous one is for being vulnerable with a stranger and asking for help.

I can do what I am there to do as a crisis counselor, and maybe, that’s enough.