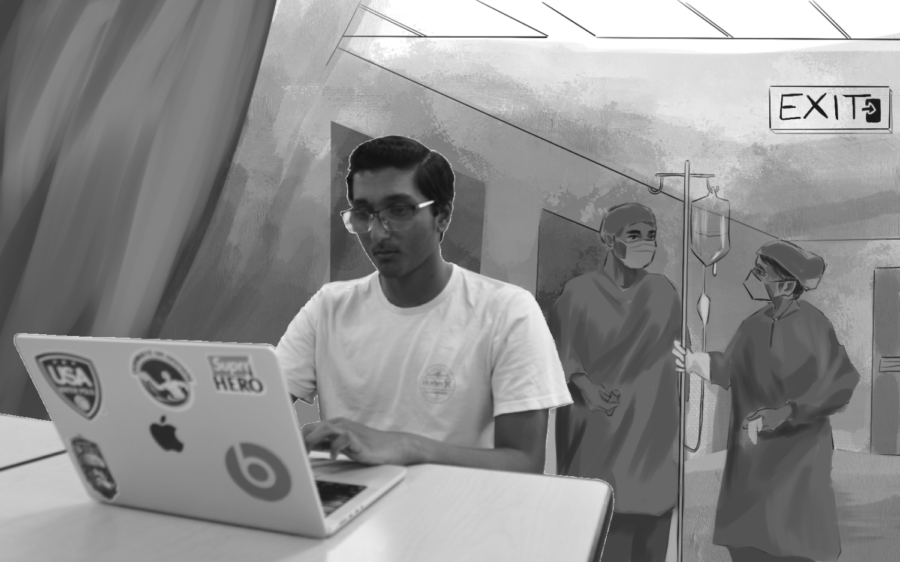

Iyengar interns at hospital in India

September 16, 2022

Rahul Iyengar (12) started his day in the office across the hall from Rangadore Medical Hospital’s dialysis ward in Bangalore, India. In the second out of four rows of tables, Iyengar opened his monitor to research dialysis, a procedure used to remove excess fluid or waste products from the blood of patients with kidney failure/disease. On this particular day, he was researching the varying costs of heparin, a medication used to prevent blood clotting.

This summer, Iyengar interned at the hospital for a month while visiting Bangalore, where his grandfather lives.

“I was looking around and saw on the Bangalore Kidney Foundation [website] that they were looking for volunteers, so I reached out,” Iyengar said. “I wanted to work with a hospital because I’m really interested in the medical field due to the fact that [someone close to me] has a disability. Her suffering has really made me want to go into the medical field and just do something.”

Going into the role, Iyengar learned that the Bangalore Kidney Foundation provides subsidized costs for dialysis.

“India doesn’t provide free dialysis for its patients,” Iyengar said. “Instead, it’s actually pretty expensive. I would say it probably costs around $20 to $30 each day, so for the majority, it’s a very costly thing. With donations, the foundation is able to bring down the cost to approximately $10 a day.”

Through his research, Iyengar was able to find a cheaper alternative to agents like heparin used during dialysis.

“I was mainly looking into the chemistry involved with the dialysis process,” Iyengar said. “There’s a dialysate and blood-thinning agents that are used, and I was looking at alternatives to what the hospital had already. Eventually, I found one that was 40% of the original cost.”

The hospital is now in the process of implementing the alternative Iyengar found by initiating a series of tests on patients and monitoring their reactions.

Wanting to further help the hospital, Iyengar digitized the dialysis patient database in his last two weeks there.

“I was fixing their [patient] charts, and I created a schedule on when exactly the patients came [to the hospital]—from what times they [arrived’ at, what days of the week, how many times,” Iyengar said. “I just tried to get a schedule of definite times that they come.”

He was able to digitize approximately 95% of the schedules for the hospital’s dialysis patients by creating an online spreadsheet including each of the 255 patient’s name, age, ID, payment source, times and dates they visited as well as the corresponding shift number. Iyengar said he hopes that the remainder of the patients will be much easier to implement with the completion of his groundwork.

Alongside the database, Iyengar also shadowed a doctor for approximately two hours each day, noting down the doctors’ diagnoses for patients and the prescribed medication along with details on symptom progression. Being fluent in Kannada, one of Bangalore’s native languages, aided Iyengar while communicating with patients.

“I gave whatever help I could to the nurses and other attendees, whether it was communicating with the patients or giving other aid,” Iyengar said. “One instance, there was a male in his late 60s. He wanted to have his bed raised, but he wasn’t able to communicate that with the attendees because they didn’t really speak Kannada. They spoke Hindi and English. So I was able to help translate.”

At the end of his internship, Iyengar presented a report to the President of the foundation on his work throughout the month and the implementation of the online spreadsheet.

“It was mind-blowing to witness an operation like this that serves about 300 patients a day,” Iyengar said. “There were four different floors that were having dialysis, and the process that it took to serve all these people was the biggest thing I learned.”

Kevin • Sep 18, 2022 at 8:38 pm

Cool internship