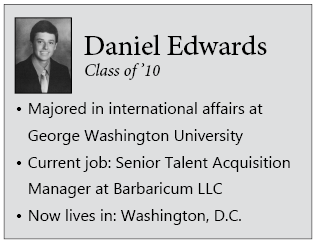

Edwards steps away from Capitol Hill

December 17, 2021

For about as long as he can remember, Daniel Edwards has lived a life surrounded by politics.

Some of the first things he ever read were the words at the bottom of the TV screen while his parents watched the Today show.

“A lot of [my interest in politics] really does come from the Today show, of all things,” he said. “I guess it kind of just happened from osmosis.”

Today, in D.C., Edwards works as the senior talent acquisition manager for Barbaricum, a government contractor that provides support in national security missions, from cybersecurity to communications.

His current position comes across as, in Edwards’ words, “a very D.C. story”—one heavily based on people he met and the connections he made.

When he was a freshman at George Washington University heading home for Spring Break, the then-congressman Brian Bilbray, R-San Diego, was on his flight back. After Edwards introduced himself and inquired about a potential internship, Bilbray told him to call his office.

After spring break, Edwards called the office and secured an interview. In the summer, he learned he would be working in the office in the fall semester of his sophomore year.

In Bilbray’s office, Edwards’s tasks were mostly administrative in nature. He took calls, led tours in the Capitol building, and sorted mail, while occasionally going to congressional hearings and bringing notes back to the office.

Edwards worked there in the fall, and stayed for a second term. During his second semester, the director of communications for Bilbray’s office, who worked for John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign, asked Edwards if he wanted to work in the Senate.

“I was like, ‘oh man, that’s the dream,’” he said. “So he got me set up with an interview in McCain’s office.”

In McCain’s office, Edwards’ work was still sometimes administrative, but was now a lot more regimented.

“I was actually in the correspondence system,” he said. “Sorting mail and attending congressional hearings was certainly still a thing, but part of my job was also some of the more advanced stuff, like greeting dignitaries before they come into the office.”

Being able to see the nitty-gritty of Congress, Edwards said, was an enlightening experience.

“When you’re there, you definitely get a sense of how important staff is,” he said. “You realize that it’s not really just a member or a senator who is running the show, and you get a lot of appreciation for the staff work.”

As an intern, Edwards was part of the political process, where he got to see different aspects of it firsthand.

“There was one time where [McCain] was like, ‘yeah, you want to just go with me [to a meeting?]’” Edwards said. “He was with another high-level foreign ambassador, and we took the subway from the Russell Senate building over to the Capitol. And he let me sit in on this meeting that was all about Russian aggression. It was really cool to be included in that.”

But, while Edwards said that the resources on the Hill, from the Congressional Research Service to the Senate Library made Capitol Hill a great place to be, the institution as a body lost a lot of its luster for him after spending four semesters there.

“It’s obviously really cool to be in the same building that you see reporting on all the time, and it feels like you’re meeting celebrities when you see famous congressmen pass through,” he said. “But you also have to see some really unfortunate decisions. Maybe you’re working with someone who’s trying to get an amendment on a bill you’re really excited about, and it gets crushed.”

One of those decisions, Edwards said, was the result of the Manchin-Toomey Amendment, S. Amdt. 715. The bill was proposed a few months after the Sandy Hook shooting, and would have required background checks on most private party firearm sales.

“The big refrain was that something like 90% of the country agreed that background checks should happen,” he said. “And the bill was filibustered, meaning that it needed 60 votes to pass. A lot of the members of the families of the children who were there were in the chamber. Vice President Biden was presiding—it was a big deal.”

But the bill was defeated. It only gathered 54 votes of the 60 it needed to pass.

“That was a big turning point for me,” Edwards said. “Like, are you kidding me? We couldn’t get this done? I’m sitting just feet away from these parents who are still mourning, who had their heads in their hands, and they’re crying as they’re leaving the gallery. It was awful. You really see the price of inaction.”

Edwards said that watching government unfold before him has made him more pessimistic about politics.

“I enjoyed my time there, but I’m grateful in certain ways that I didn’t end up there,” he said. “Seeing my former coworkers, the people I know and love, kind of vacillate between pride and absolute depression, it’s hard.”

Edwards said that the timing was never right for him to stay on Capitol Hill.

“There was a point at which I wanted to go into politics, or maybe even run a campaign,” Edwards said. “Sometimes the timing has to work out, but generally, I was applying to Democratic offices. And because I had worked for a Republican, even one with good relations like McCain, it’s still an “R” next to your name. That was definitely part of how I stepped away from that.”

Edwards found his current job a few months after he graduated. After a few years in talent and acquisition, his boss at the time found a job in the Trump Administration. As spots continued opening up, he became the Senior Talent Acquisition Manager for the company, a job that requires interpersonal skills, and above all, curiosity.

Edwards said that a lot of his recruiting skills carried over from learning how to ask questions during his time in high school working on The Nexus.

“A big part of my job is interviewing,” he said. “It’s not just about knowing if they fulfill the requirements, it’s also about hearing about their outside interests.”

While he didn’t initially expect to be where he is, Edwards said he’s grateful for how it turned out.

“It definitely feels like, in a way, you’re living the dream,” he said. “You’re in D.C., you’re able to sort of hack it in a city 2,600 miles away from home. There’s pride in that.”

Edwards said that as a senior, both in high school and in college, his life ended up pretty different from how he envisioned it at those times.

“I think there is some utility in having dreams and goals at certain points in your life,” he said. “It is just a matter of reconciling that with reality down the road and not being too hard on yourself for not doing exactly what you thought you wanted to be doing or what you thought you would be doing.”

For Edwards, that reconciliation has sometimes been a challenge.

“[In high school], I applied Early Decision to GW, and I was really decisive,” he said. “I knew I wanted to work on the Hill, and I ended up working there and thought I’d stay forever. I didn’t, and now I’m here, and I’m doing fine. It’s good to have those points of reference to steer you in the right direction. But I think I definitely put too much stock in that at too young of an age and it may have prevented me from considering other avenues that could have been equally enriching.”

Edwards said that he credits a lot of his success to his time at Westview, and on The Nexus. Especially in high school, he said that the things he did were extremely important to getting him where he is now.

Still, it’s not everything.

“It’s extremely important to take care of yourself,” he said. “You’re forced to learn a lot about yourself in those four years of high school. And you should listen to what your body and your heart and your brain is telling you in terms of what you can take on and what you can’t.”

For Edwards, that means being willing to change.

“Even if things don’t pan out the way you want to, you sort of just hope that the skills and knowledge you’ve attained over the years will sustain you going forward,” he said. “You know, your senior year of high school and your freshman year of college is not a life sentence. It is good to have goals, but to not let them define you or your trajectory.”