Crowley studies history of universe

December 17, 2021

Kevin Crowley spends his time trying to solve the unanswered questions of the universe. He works at UC Berkeley as a postdoctoral researcher in cosmology, which is a particular branch of physics that examines the chronological development of the universe.

Kevin Crowley spends his time trying to solve the unanswered questions of the universe. He works at UC Berkeley as a postdoctoral researcher in cosmology, which is a particular branch of physics that examines the chronological development of the universe.

On a day-to-day basis, he works as an experimentalist to obtain data and measurements from waves and certain frequencies of light in space. He specifically researches something called the cosmic microwave background, which consists of remnant radiation from the formation of the universe. Although these waves may seem minor to those not working in cosmology, Crowley said they are incredibly important.

“When we go out to look for [these waves], they’re easy to find,” Crowley said. “But what we’re trying to pull out is a very tiny signal, which will have little variations that can tell us about the early universe and about the universe’s history. It can tell us what happened between the time that light was emitted to today, which is essentially the whole 13-billion-year history of the universe.”

While there are a lot of things that he studies in his work, Crowley’s main focus is analyzing lightwave data. He and his team have taken a special interest in the polarization angle of the light as it has shown to create unique patterns.

“The pattern we are looking for would tell us about the earliest times in the universe,” Crowley said. “We don’t really know anything about that initial state of the universe, other than that we can model it and have some interesting ideas for what might be there. Getting direct proof of it has not yet been possible, but it is possible that this one pattern of that light polarization could tell us better about the universe’s moment when inflation turned on and how energetic it was. It could tell us how space-time expanded.”

According to Crowley, although the answer will have little impact on the general population, the answers about the early universe that this research will provide would be groundbreaking in the physics field.

“[This question] is truly academic as far as everything else is concerned but, to me, this question and the answer is just a momentous idea,” Crowley said. “It’s inspiring trying to do stuff that sounds like it would never be possible.”

Trying to find the answer to these questions has been Crowley’s main research goal since entering his postdoc researcher position in 2018, but he says he won’t stop even after he can find the answer to this question.

“Realistically as an experimentalist, I would just keep going to the next question that has yet to be answered,” Crowley said. “Looking for ways to poke at the model is always what experimentalists are trying to do.”

Currently, Crowley’s days are filled with three different types of responsibilities. He works as a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, as a collaborator on experiments that utilize the Simons Array Telescope, and as someone in research and development for technologies related to similar telescopes.

[metaslider id=”11213″]

“There are projects that are running now and some that have already run but need their data to be analyzed,” Crowley said. “There are also projects that are being built right now. Even beyond that, there are projects that are more about research and development that [are focused] on making a tinier version of something or prototypes to push ahead on a particular technical question. All of these things are happening all the time. The biggest part of my day-to-day life is juggling between all of them.”

With the Simons Array, Crowley collects data to make a better measurement of the microwave background. Simmons Array is a next-generation cosmic microwave background (CMB) polarization experiment that targets obtaining precise measurements of polarization patterns. The experiment is conducted using telescopes at the Simons Observatory in Northern Chile.

According to Crowley, Simons Array is about making three copies of a telescope and operating them simultaneously to triple the data collected. In his role, Crowley works on developing a smaller scaled version of technology found in telescopes to record and detect measurements.

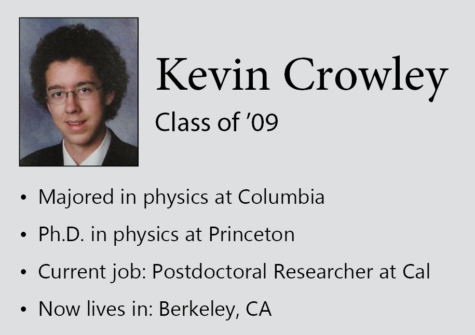

Getting to this point in his career was not without many accomplishments. In order to gain the skills necessary to help with all of these projects, Crowley majored in physics at Columbia University and then earned a Ph.D. in physics from Princeton in 2018. Despite this, Crowley wasn’t always sure about physics as a career.

“When I left for college (in 2009) I was interested in a lot of different things,” Crowley said. “I did physics at Westview and was really interested in it, but I also wrote a lot for the newspaper. I cared a lot about English. I ended up doing English classes at Columbia and Philosophy classes. I tried to keep a broad scope.”

Crowley said that he set his sights on physics halfway through his undergraduate studies after taking a few physics courses with excellent lecturers.

According to Crowley, one of the main reasons he loved the humanities was how there was always more to learn about it and an intense creative aspect associated with it. This was something that Crowley later discovered to also be true about physics.

“[Physics] takes a lot of creative energy and stamina,” Crowley said. “The really excellent experimental physicists have to be creatively thinking about how to solve engineering problems in the design phase, creatively thinking about how to solve just any kind of problem that comes up when you’re actually measuring the data, [and] think[ing] creatively about how some problems come up and you’re analyzing the data.”

When Crowley was a student at Westview, he took AP Physics C with Mrs. Hester. Looking back at that experience now, Crowley said that she also play a large role in his eventual decision to become a physicist.

“Mrs. Hester as an AP physics teacher was sort of the first positive impulse towards [physics],” Crowley said. “For me, the natural inclination when beginning with physics was to get really frustrated when something wasn’t becoming clear immediately, and Mrs. Hester was excellent at just walking everybody through the right way to think through those problems and stuff. She also made it really fun. All the hands-on stuff that we got to do is really, really enjoyable.”

Crowley’s love of learning only grew while studying physics. According to him, it seemed to naturally culminate in a love of research, which is why he decided to become an experimental cosmologist.

“Research is essentially just many [series of] decisions that you make every day,” Crowley said. “Some things are very clear whether they worked or not and it doesn’t take long to find out, but for other things, you might wait months to find out if they’ve worked. You also have to be okay with that uncertainty for those long periods of time. You just learned how not to treat that stuff as if it’s a personal failure, hopefully, then you can treat it as just the price of doing business to some extent.”

In the three years that have passed since earning his Ph.D., Crowley has continued to learn a lot about himself and the world through his career. According to Crowley, physics comes with a constant environment of learning as he can never say he is completely done or that he understands everything. However, accepting that he will never know everything is something that Crowley admits to having struggled with.

“Your training as a scientist is that you come in knowing some stuff to work and then you almost realize daily that you don’t know something that you could know, or that would be beneficial to know, because a new problem has come up,” Crowley said. “Fighting your own ignorance and recognizing that you don’t know everything are definitely cornerstones of the job.”

With all that he has gained from his career so far, Crowley hopes to continue progressing with his work. He is currently applying to various research centers to land a permanent research position in cosmology. According to Crowley, this round of applications and the self-examination that it has forced upon him reminds him of high school and applying for colleges.

Although completely different in circumstances, Crowley said that both periods of his life have allowed him to gain a much better understanding of himself.

One major difference, however, is Crowley’s acceptance of rejections.

“Getting rejected is never fun, but that’s the most personal time for [growth],” Crowley said. “There is not much you can do to sway an organization or college. Self-presentation is important, but I don’t think a rejection necessarily is all on you. Rejection, in a lot of cases, weighs more on their needs and not you personally.”

In the end, after applying to colleges in 2009, graduate schools in 2013, and to research centers in 2021, Crowley said he has learned a lot about himself and what he should focus on in these crucial transitional stages in his life. His biggest take-away has been to stay open to new ideas despite how much experience he has.

“Be honest with yourself,” Crowley said. “If you’re having a hard time with something, acknowledge that. Find some space to think about why that is. If you’re dreading something, remember that the more you can get a clear idea of where you’re at, the better things tend to go.”

Although he has to always adapt to new discoveries in his field, Crowley sees his career not as something unstable, but rather as something full of potential. He is curious to see what is coming next. As he looks forward, he urges students interested in physics to fight fears of uncertainty.

“Physics is not always fun, especially if there are things like time pressure or if things aren’t working right,” Crowley said. “But as long as you can keep that uncertainty about what’s going to happen from being anxiety-producing, it will get easier. If you can fight that initial feeling of being really scary and turn it around to focus on the potential there [is] for amazing things to happen, you will be okay. As long as you can be hopeful and not let that uncertainty rule you, [physics] is a great field and a really cool way to spend your time.”