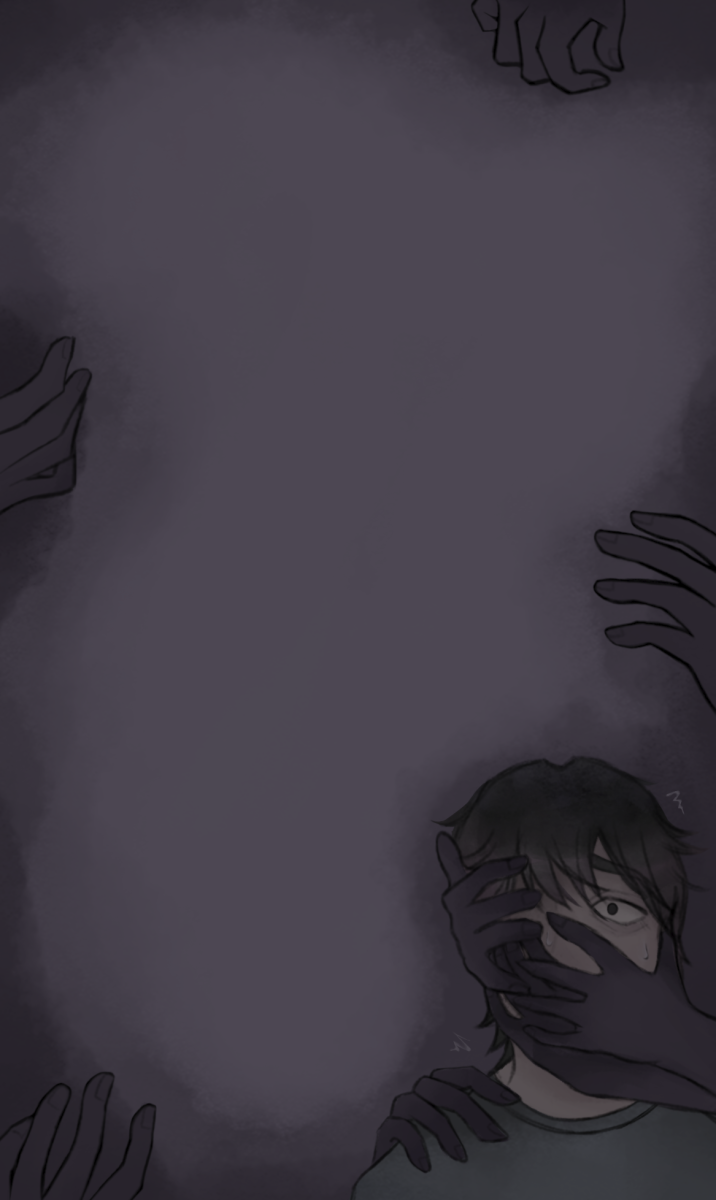

It was Claire Choi’s (11) freshman year, and she was walking through the streets of Seoul, South Korea. Everywhere she went, advertisements for plastic surgery flashed. On the small phone screen she held in her hands, in clothing stores, and on television, she saw them. The advertisements caused Choi-–and people all around the world-–to feel insecure about their bodies.

“I would always see people watching what they eat, hating on their body, using extensive editing on their photos and just not [being in] a good place of body positivity,” Choi said. “It was just a lot of fakeness and hate.”

When Jasmine* was 14, as she watched the Winx Club, she compared herself to the cartoon characters with unachievable animated bodies.

“[The characters on the show] had hourglass bodies and I was like, ‘I want to look like that’ because they were my favorite characters,” Jasmine said.

She also compared herself to “real” girls on social media and seeing someone smaller than her raised questions of her own body at the age of 12 or 13.

“There was this girl [online] and she was super thin,” she said. “I was like, ‘Am I supposed to be that skinny?’ And it really made me feel bad. I was like, ‘Why can’t I have that body?’”

When Jessica Harris (12) played with Barbie dolls and watched princess movies, she would compare her body to those made of plastic and ink.

“I remember playing with Barbies, either in preschool or Kindergarten,” Harris said. “I remember comparing myself to Barbie even though Barbies back then were not realistic to what humans looked like.”

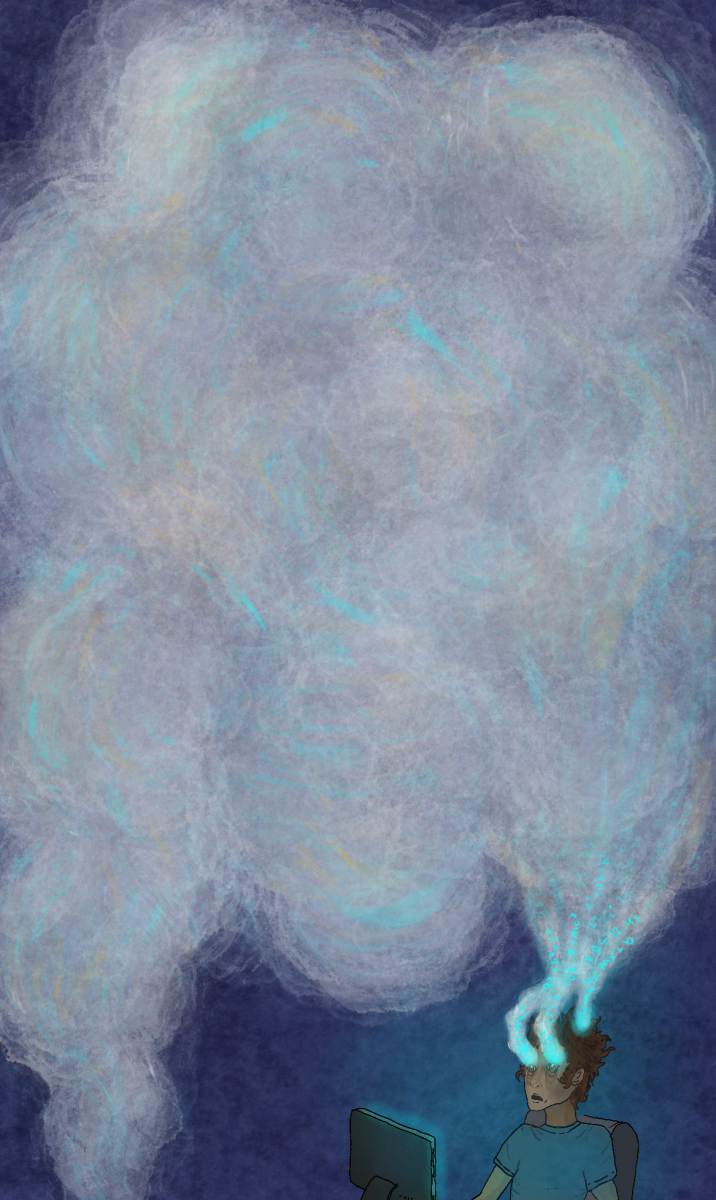

Dr. Sophia Choukas-Bradley, assistant professor of psychology at University of Pittsburgh, is the corresponding author of a theoretical review paper on the role of social media in adolescent girls’ body image. She said that people are naturally drawn to engage in social comparisons, and social media only accentuates that problem.

“The problem with social comparisons on social media is that they tend to be ‘upward social comparisons,’ meaning we compare ourselves to people we perceive to be more attractive than us,” Choukas-Bradley said. “One of the reasons this is so likely to happen online is because the images posted tend to be carefully curated and often edited using filters that enhance attractiveness.”

Scrolling through TikTok, one encounters unrealistic hourglass bodies and idealized figures. Jade Becker (10) remembers looking through videos on social media in the past and feeling inferior to the idealized bodies she observed.

“I’ll see my friends or I’ll see some girl on social media in a really tiny crop top and low-rise jeans just showing her perfect hourglass body with the perfect curvature and everything,” Becker said. “And I’m just like, ‘Wow, how is that even possible?’ It makes me want to immediately do core workouts and immediately restrict my diet. It’s just really upsetting to look at images like that knowing that I can never achieve that or knowing that my body doesn’t look like that.”

Hansen Peterson (10) also finds himself looking at posts with unrealistic standards and feels like he has to change things in his life.

“There’s a lot of fitness influencers who are always posting and are ripped with massive biceps,” he said. “That makes you feel worse about yourself because you feel like you could never get there. [It] sets unrealistic expectations.”

These unrealistic standards make Peterson feel as if he needs to be doing more to achieve the ideal body.

“It makes me feel like I should use my time better,” Peterson said. “It makes you think deeper about what you’re doing in everyday life because you feel like you’re not doing what you should be doing. [I think] ‘I should be working out right now. I should be eating something else.’ Even though you should just be enjoying yourself and doing what you want to do.”

Dr. Marika Tiggeman, a professor in the College of Education, Psychology, and Social Work at Flinders University in Australia, said that celebrities and influencers conform to beauty ideals. Unlike traditional celebrities, influencers come off as more relatable and like one’s friend, making social media feel more personal. As a result, many regular people feel the need to conform to these ideals as well.

“Ordinary people take great pains to only post photos in which they look attractive,” Tiggeman said. “So, although social media should be about everybody, it still ends up presenting idealized bodies and lives.”

Becker said she finds herself comparing her own body even to those of her friends.

“Because I have social media, I’m seeing other people go to the beach in bikinis or other people [wearing] their Homecoming dresses,” Becker said. “And they look so much skinnier or prettier than me and then I get a little bit upset.”

Choukas-Bradley said that a number of psychological and interpersonal factors that occur in teens make the social comparison problem more relevant to them.

“Teens are highly attuned to social norms,” Choukas-Bradley said. “The biological and cognitive changes that happen during puberty make adolescents especially attuned to physical appearance and attractiveness. Even before the advent of modern social media, teens experienced a social-cognitive phenomenon that psychologists call the ‘imaginary audience,’ in which adolescents feel acutely self-conscious and as if they’re living in a spotlight. Social media has created a world in which this audience may no longer be imaginary, as any moment can be captured and broadcast online.”

When Becker sees a picture of herself, she often questions if that is what she really looks like and finds herself nitpicking her body.

“I’ll always zoom into my body when people take pictures of me, always zoom into my face, always zoom into every part of me,” Becker said. “And then I’ll see my friends’ social media or I’ll see an Instagram model, and I’ll be like, ‘Wow, this looks so good.’ I’ll even see people online who look totally different than they do in person. And that’s just kind of a reminder to me that not everything’s the way it appears [online], but in the moment, it’s really hard to see that, especially when everything is perfect and their body is perfect. They seem so toned and like they have the perfect lifestyle. They eat Acai bowls all day and go on hikes and runs and I’m sitting in bed eating chips and watching a murder documentary on Netflix.”

According to Choukas-Bradley, quantifiable feedback on social media posts can reinforce appearance ideals.

“If adolescents witness peers, influencers, and celebrities receiving appearance-focused comments or high numbers of “likes” for photos that highlight physical beauty, they may learn to associate physical attractiveness with approval, validation, and status,” Choukas-Bradley said.

When looking through social media apps in the past, Choi said she has opened the comment section and felt worse about herself afterwards.

“In middle school, I remember I would go on Instagram, and I saw everywhere posted standards on bodies, and I saw a lot of comments on it,” Choi said. “People were commenting, ‘She’s too fat. She’s too skinny. She doesn’t look right,’ and nitpicking everybody, which made me feel self-conscious.”

When Choi had to move to Seoul, South Korea during her freshman year of high school, she said she felt that the beauty standards in America versus Korea were very different and confusing. She felt as if she had to conform to these new body ideals, which included paler skin and a taller height. This changed her expectations of her body and skin color.

“In Korea, the beauty standards are crazy slim—slimmer than here [in America],” she said. “They promote slimmer hands, legs, everything. You’d see advertisements and products and editing everywhere to make themselves as pale as possible, which is very different from here. I grew up in America and I was like, well, what is the sudden change in the standard? It was like a complete 180. It definitely influenced the way I feel. I thought I had to be taller.”

But despite the beauty ideals for women being highly publicized, Peterson says that he feels like there is more talk about body positivity for women.

“There are a lot of accounts that I notice that talk about how [girls] should ‘just be happy with yourself and don’t try to appeal to anyone,’” Peterson said. “But I feel like there’s not really any of that for men. If it does happen then other guys just are like, ’oh, this guy is so weird’. It’s looked down upon to try to be nicer to yourself.”

Harris, who has had a passion for singing and acting in theater since third grade, has observed body stereotypes in men, not only in the theater world, but on television as well.

“I see bigger men getting cast as the funny side character even in TV, shows, and movies,” Harris said. “We always see the ‘not as conventionally attractive man’ who’s also really funny being best friends with the male protagonist.”

To combat the negativity on social media, Harris, Becker, Jasmine, Choi and Peterson have all found ways to deal with what they see on social media.

Becker said that “What I Eat in a Day” videos and posts of people she perceives to have a perfect body on social media pull her into a spiral of negativity around her body and the food she eats. In trying to find a solution to this problem, Becker has taken steps to curate her feed so that she sees less of things on social media apps that make her feel bad about herself.

“Don’t be afraid to press ‘not interested,’ because it really does affect your feed and affect what you look at,” Becker said. “Look at more stuff that makes you happy and less [at] pretty people on social media. If someone makes you feel insecure, don’t be afraid to not look at their Instagram feed.”

Choi has also curated her feed to be more positive.

“I follow a lot of body positivity girls on social media and it definitely changed what I look through on social media,” Choi said. “Sometimes I’ll repost a couple of things and like it, or share it to my friends.”

Besides the guilt and shame that the media can make people feel about their bodies, it can also help them feel represented and that their body is normal and common. Choukas-Bradley said that social media can expose people to a wider range of beauty standards.

“For many years, teen girls were bombarded with images of thin, white women in mass media, whereas now, through social media, teens are exposed to a more diverse range of images in terms of size, shape, and color,” Choukas-Bradley said.

Becker said that seeing her body type in the media puts her in a positive and self-loving mindset, making her feel like her body is loved and normal.

“The first time I saw my body in the media was, surprisingly, the Victoria’s Secret fashion show,” Becker said. “My mom does design and I grew up watching stick-skinny, super-tall models on the runway. So, in a way, seeing someone who had curves and maybe wasn’t as tall, but still elegant and beautiful, made me feel super proud. I know that’s super backward because most people hate Victoria’s Secret fashion shows, but seeing that in the media gave me confidence.”

Harris said that plus-sized actors performing on Broadway give her hope that she will someday play a leading role. She was especially inspired when Bonnie Milligan, a plus-sized performer, won the prestigious Tony Award in June.

“She is one of the only people who has won a Tony for a role on Broadway and who is plus-size, and it was so empowering,” Harris said. “In her speech, she said something along the lines of, ‘If you don’t think that you can earn anything because of how you look or your race, your ethnicity, et cetera, look at this.’ It was just such an amazing night for people who aren’t represented enough in the industry.”