Sitting in her first period class running on four hours of sleep, Sophia Liu (12) felt the room spinning around her as she began to doze off. Even though her teacher was talking, his voice was drowned out by the throbbing in her head. She felt her heavy eyelids drooping as she struggled to stay awake. This isn’t a rare occurrence for Liu. Almost every night, she goes to bed at 4 a.m. and wakes up for school at 8.

“I’ve noticed that my head hurts a lot, especially in first period, and also in classes where there’s a really long lecture, I have a hard time focusing or staying awake,” Liu said. “I feel like the biggest impact [my lack of sleep] has had on me is that I’m always late to things in the morning because it’s really hard to get up, and every day is a struggle.”

Similarly, Lindsay He (12) struggles with going to sleep, in part, due to her challenging classes and putting off her homework until later. However, more than anything, she has a hard time breaking her sleep cycle.

“It’s a mix of procrastination, homework, and bad habits from previous years,” He said. “[I’ve been] able to get away with procrastinating later and later, until it [feels] like I have to finish [my work] very late at night.”

Working with many high-schoolers similar to Liu and He, Dr. Amanda Ji, a pediatrician at Family Health Centers of San Diego, said she has witnessed an increase in sleep deprivation cases among teenagers.

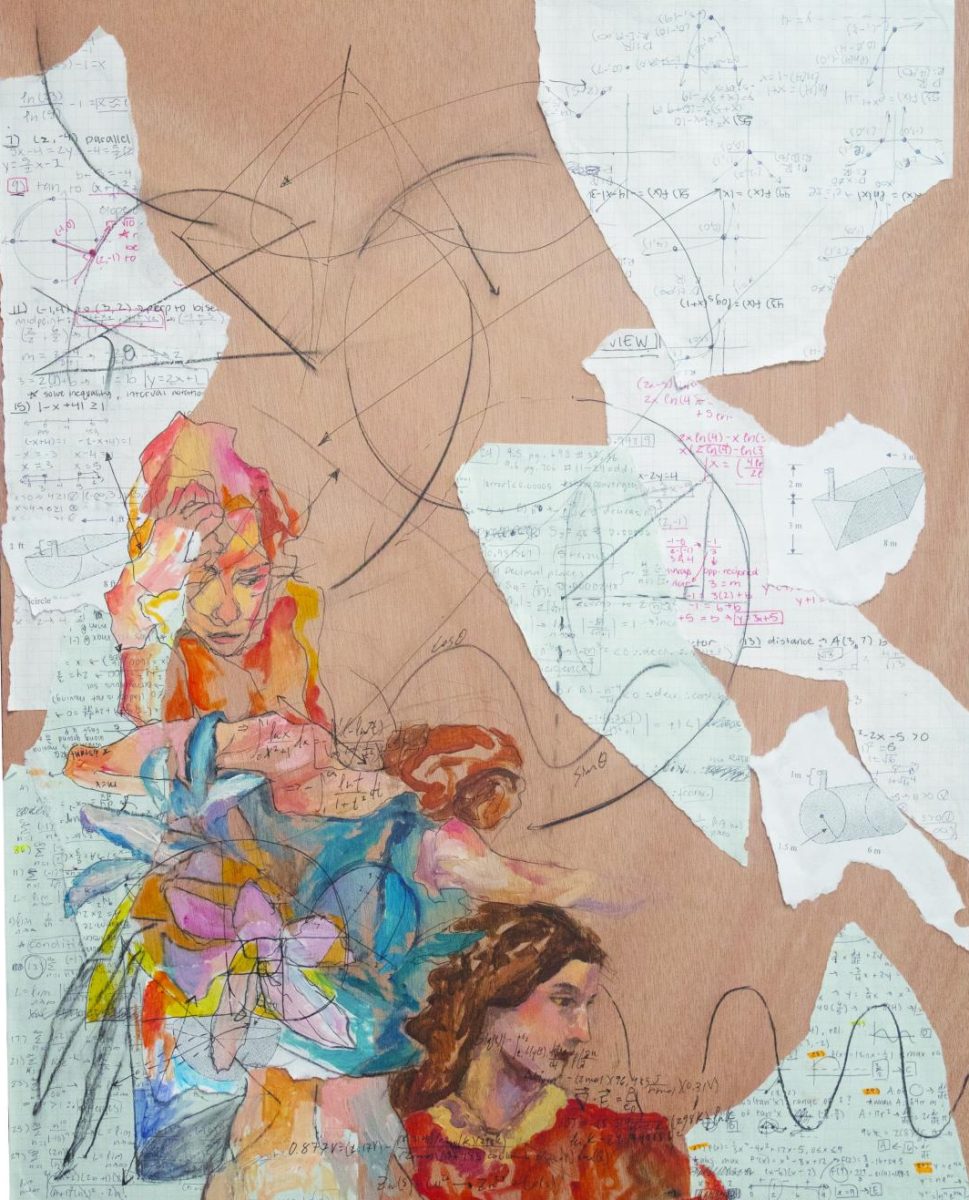

“I have seen a vast increase in sleep concerns in all ages, starting at 2 years [old], but especially in teens,” Ji said. “I think screen time has been a big factor in this across all ages. So many things that we do during the day can affect our sleep: how active we are, our stress levels, and what we are eating. Teens are also under more stress and academic pressure, [which] may also be playing a role in sleep deprivation.”

Like many Westview students, Liu is not a stranger to academic pressure. As her coursework accumulates, her average amount of sleep per night decreases.

“My classes are the main factor [in losing sleep], more so than procrastination,” Liu said. “I’m a slow worker in general, and as the year goes on, everything just piles up and makes it really hard to get things done.”

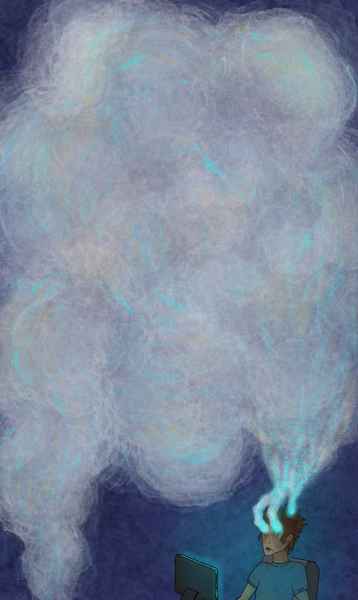

Liu’s bedtime is pushed further and further back to keep up with each class’s curriculum, leaving her stuck in a negative feedback loop. According to AP Psychology teacher Laura Cox, the best thing to do when dealing with homework build-up is to sleep and continue the next day, since students who get less sleep are not fully cognitively conscious.

“The longer you stay up, [the more you create] a vicious cycle,” Cox said. “You have to go to bed even if you don’t get your work done because the next day you can learn better in class. You need to get more sleep because it’ll change everything. It’s a different level of consciousness to be sleep-deprived. If you get adequate sleep, you will need to study less because you can function as your brain is designed.”

Ji attributed teenagers’ tendency to prioritize schoolwork over sleep to a core ideal of American culture.

“I think we place a larger value on productivity than other countries do, and therefore, the value of sleep gets pushed to the sidelines,” Ji said. “I think the biggest [misconception] is that sleep isn’t important.

This misconception is one that He said she has maintained throughout high school, and she said it has caused a lot of personal strife.

“I always treated [sleep] as something that wasn’t that important to me, because unlike homework, it’s not due the next day,” He said. “No one’s going to know if you got less sleep, but you’ll know if you didn’t finish your homework. I think it’s the feeling of security. [Knowing] that you already know the content before you go to sleep is a lot more comforting than if you were to go into the day without knowing anything. I’m constantly fighting between the two sides.”

However, not meeting the recommended amount of sleep per night is usually very obvious. Cox said that she can spot when her students haven’t been sleeping enough.

“I can tell when kids are not retaining [the lesson],” Cox said. “They’re distracted by things. A kid [could have] been in regular attendance and will still say, ‘When did you say that?’ Or ‘I don’t remember this.’ They’re telling the truth that they don’t recall it, [because] they were there in body, but just not in any level of consciousness to learn it.”

Despite admitting to being tired and dizzy during school hours, Liu said that the fear of not getting into a good college and having a successful job is what keeps influencing her to continue sacrificing her sleep.

“I feel like if I put in this work, I’ll probably get further or do better [in my life], and I guess that’s a huge motivator for me to keep staying up late as opposed to going to bed early,” Liu said.

Cox said this mentality backfires and that going to bed earlier is also highly important to one’s education, as the brain doesn’t remember what it’s learned until the body undergoes deep sleep.

“You need to go to bed in order to allow what you’ve learned that day to consolidate into long-term memories,” Cox said. “We have the hippocampus, which is like a video recorder; it’s a loading dock for memories. If you don’t sleep, [the memories] never go to long-term potentiation. That’s what’s making the working memory. It sends it into these long-term areas, and there are only certain times it can do that, and one of them is during sleep. So if I study and do all this homework, and I only sleep a few hours, there’s not even an opportunity for that to go into my long-term memory.”

Cox said that she’s observed many of her students being frustrated over not remembering what they’ve studied, most likely due to a constant lack of sleep.

“[Kids say], ‘I spent so long on it, I studied so much,’ and then they start to feel like they’re dumb or not good enough, but they didn’t even give their brain a chance to save their memories,” Cox said. “It only does it during these windows of time. Your body is designed to send those things that you’ve studied and you spent time on [to long-term potentiation], but it’s doing it during sleep. It has no time to put it away into long-term memories, so they just bounce out.”

In an attempt to change her sleeping habits, Liu said she has tried to shift her bedtime to an earlier hour; however, it has been a challenge breaking out of the cycle.

“I’ve definitely tried to [go to sleep earlier], but I feel like once you get in that habit, it’s really hard to get out, so the most I’ve been able to change [my sleep schedule] is probably half an hour at most,” Liu said.

Cox said that even if people get one less hour of sleep, it makes a big difference.

“REM sleep, which is our dream state, is when we’re consolidating memories,” she said. “That one less hour [of sleep] is not just one less hour. In a 90-minute cycle, you go through REM, non-REM 1, non-REM 2, non-REM 3, action on REM 2, and then REM sleep, and then you start the cycle over. But throughout the night, the REM gets longer and longer, and you need that. One less hour actually is exponentially less because at that hour, the REM would have been longer than it was all previous times. So it’s worse than just one hour and what you think you’re losing is a bigger deal than you think.”

He said she compensates for missed sleep by napping after school, giving her the energy to finish everything she has to do.

“I take a really extended nap,” He said. “It helps because otherwise I get really tired early on. I feel like I can’t finish all of my homework without getting extremely tired to the point where I just naturally fall asleep.”

However, Cox said that taking long naps is not a good solution because it disrupts REM sleep and makes it harder to fall asleep at night.

“The problem with [naps] is that they are going to keep you up later, and they’re not enough,” Cox said. “It’s more sleep, but if that’s keeping me up until 2:00 or 3:00, then that is not a functional system because you need to loop the sleep together. It needs to be together to get the maximum benefit in the important stages that benefit us and consolidate our memories. If you’re creating a system where you have two different sets of sleeping, you have to break it. You have to just make yourself stay up. Get your work done and go to bed earlier. It’s so hard the first day, but that’s that vicious cycle that you have to get out of.”

In addition, Cox said that trying to change your body’s circadian clock to sleep later doesn’t just give you worse sleep; it’s cancer-causing.

“It’s creating a cycle that your body is not meant to be in,” Cox said. “One of the things [scientists] labeled as a carcinogen is working during night shifts. People used to think you could just train your body to be a day sleeper, but we can’t. Our body is not designed for that. And so, it drastically changes the quality of your sleep.”

To fix an unhealthy sleep schedule, Ji recommends creating a consistent sleep routine, which allows the brain to unwind and prepare for sleep.

“Our bodies thrive on routine and schedule,” Ji said. “Having a set bedtime is important for all kids, teens, and adults. I typically recommend the sleep routine starting around one hour prior to bedtime and eliminating screen time two hours prior to bed. An example sleep routine would be turning off TV/laptops, taking a shower, brushing teeth, and reading a novel. Once your body starts to recognize the sleep routine, it will ultimately be conditioned to get “sleepy” at the start of this routine. Also, the state of the room matters. Keeping your room tidy is very important to optimize relaxation and minimize stress.”

Cox explained that if electronics aren’t turned off about two hours before bed, the blue light emitted from screens keeps people awake.

“When it’s dark, your brain lets melatonin secrete,” Cox said. “When you’re staring at your phone, the whole message system that goes to your hypothalamus and all the things that release melatonin to make me sleepy naturally are like, ‘Oh, stop guys.’ If it’s [bluelight], my body’s like, ‘I need to pay attention.’ But if I’m just staring at my phone, my body is putting [melatonin production] on a pause.”

According to Cox, this is a big problem because if teenagers are still on their phones late into the night, it reduces their lifespan significantly.

“Being chronically sleep-deprived shortens your lifespan,” Cox said. “It actually exacerbates and accelerates the deterioration of my telomeres, [which are] the ends of chromosomes, the tips. They are indicative of our life span and how we age. Not getting enough sleep is shortening those at a faster rate. I tell my students that when they’re scrolling on their phone at night saying, ‘I’ll go to bed when I’m sleepy,’ they have to say, ‘I’m killing myself. I’m killing myself. I’m killing myself.’”

Although Liu knows how important sleep is, she said she often struggles with fitting it into her life.

“For me, [sleep] has always been like a privilege because I have to get all of these things done first in order to actually rest and heal,” Liu said.

However, Ji emphasized the importance of creating a healthy schedule that prioritizes sleep.

“It’s all about balance,” Ji said. “The main part of being a teenager is gaining independence and responsibility. Shaping your own sleep routine is one of the biggest tasks and responsibilities through high school and into college. I think viewing sleep as an integral part of well-being will help us value it more and ‘schedule’ it into our daily lives. It first starts with prioritizing sleep. Time management is critical to work efficiently and achieve balance. Being intentional and efficient with your work time is also important — you can spend two hours working on an assignment while also browsing your phone or complete it in 30 minutes if focused without any distractions.”

Ji also emphasized the importance of getting enough sleep to improve overall bodily health and functions.

“Nightly rest is crucial for all organs, specifically the brain,” she said. “Overall performance will suffer with diminished sleep. Efficiency, information retention, critical thinking, and general mood will be compromised with ineffective sleep. Having a nightly sleep routine, getting daily exercise and sunlight, and eating three nutrient-dense meals a day [with] at least five fruits and vegetables and limiting processed foods [is important].”

Cox said that instead of thinking that they aren’t good enough after studying for so long, students should see how getting more sleep affects their performance.

“When kids feel inadequate, they think that they can’t do it,” she said. “It is hard for them, but I think that before they start writing themselves off as bad test-takers, or not smart enough, or not good enough, they need to actually give their body the opportunity to do what it needs to actually learn. Let’s say that they start trying to sleep regularly and see how it goes. I guarantee that’s going to change their outcome in all their classes much more easily. It’s going to be easier and they’re going to do better.”

![Jolie Baylon (12), Stella Phelan (12), Danica Reed (11), and Julianne Diaz (11) [left to right] stunt with clinic participants at halftime, Sept. 5. Sixty elementary- and middle-schoolers performed.](https://wvnexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_1948-800x1200.png)