Stepping Outside of Isolation: Overcoming Monotony in the Pandemic

In appreciating the little things, Nguyen, Neuhaus work to find positivity within repetitive pandemic lifestyle.

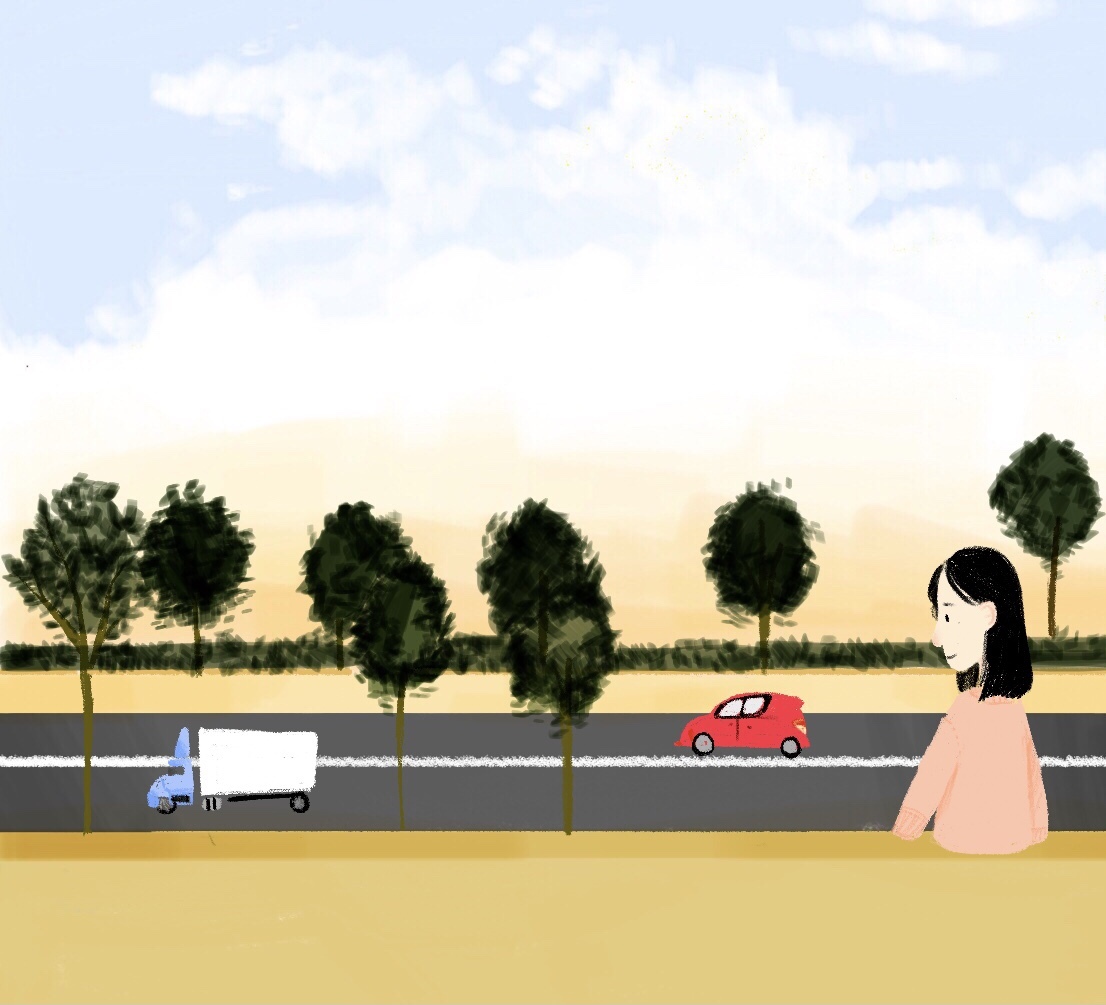

Emilie Nguyen (12) sat upon a wall just down the street of her house, watching cars fly down Carmel Valley road. With each car that passed, Nguyen was reminded that—despite her life feeling so stagnant—the world was carrying on, getting through the stress of the pandemic.

“Sitting on the wall brings me a sense of comfort,” Nguyen said. “The world feels so strangling right now, but watching the cars offers me a way to get a breath of fresh air.”

From waking up, to working out, to eating dinner, Nguyen’s daily routine became restricted to her room early on in the pandemic. Whereas other families were able to see and socialize with one another, Nguyen quarantined in her room for four weeks straight out of concern for her high-risk family. She felt suffocated.

However, as she quarantined, taking a step outside offered an escape from the four walls she felt confined to.

With her communication being limited to online, Nguyen said she got used to being her own company—an environment that allowed her to reflect on her mental health.

“The longer I sat by myself in my room, listening to the same thoughts go through my head, the more I realized [isolation] was taking a large toll on my mental health,” Nguyen said. “I didn’t understand how mentally draining [being alone] was.”

Trudging through Monotony

Nguyen’s experience in isolation is not an uncommon one. After a year in lockdown, many students continue to be stuck in the same routine which has created a mentally exhausting environment.

“I didn’t know what to do with myself,” Nguyen said. “I couldn’t see my friends, talk to teachers, or go into a new environment. It was the loneliest I’ve ever felt.”

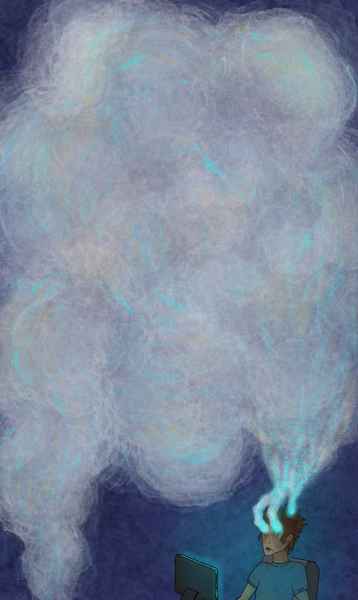

With online learning especially, Nguyen was stuck in a rut—there was no structure in her life, and she found herself losing motivation to complete what felt like the same day over and over again. Simple tasks like getting out of bed, Nguyen said, became increasingly difficult.

“Every day was pretty much the same,” Nguyen said. “In-person school offered different experiences almost every day, like talking with new people or having random things happen throughout the seven hours. But with online school, where I can keep my camera off and tune out the class, there is no real reason for me to get out of bed.”

This, according to clinical psychologist Reid Kessler, is indicative of the negative impacts that social isolation has on the development of students.

“The pandemic has been particularly hard for high school students because of the developmental needs they have,” Kessler said. “High school is a time of developing an identity and closer relationships with peers, and there needs to be [in-person] social contact for that to happen.”

Finding Motivation

The in-person schooling that students had grown accustomed to allowed them to thrive from the positive pressure that school provided. Psychotherapist and ecotherapist Amy Lajiness analogizes this idea to working out in a gym—showing that students work better when there is a sense of healthy competition.

“One of the things that is motivating is seeing other people working, accomplishing things,” Lajiness said. “When people go into a gym and see others doing workouts, people tend to work harder because you can see other people working and other people are seeing you working. So there’s this healthy sense of competition. In the context of the pandemic, [students] don’t have the same sort of examples from other students or the sense of working together where they are getting social interaction. [Students are] missing out on that component, which [can be a source of energy for many].”

For Nguyen, social contact was something that encouraged her to apply herself in school. Working alongside her peers in an academic environment strengthened her work ethic. Without this motivating factor, she began to lose her drive to succeed.

It is a common feeling, according to Kessler, to have phases of lower motivation. However, when this impedes a students’ ability to succeed in school, it can be difficult to overcome, and the pandemic has only exacerbated this. Missing out on an in-person school experience is not only impacting students’ ability to excel in school, but also their developmental needs.

Kessler said that for adolescents, this is an integral time for development due to the impressionable nature of their maturing brains. Without the stimulation one would receive from the typical high school experience, teenagers, especially those with pre-existing conditions, are left with one less way to deal with their emotions.

“My sense is that the effects of social distancing and online school have functioned as an amplifier of psychological distress for many students,” Kessler said. “Those at-risk or already experiencing elevated levels of psychological distress are likely experiencing an increased amount or severity of their symptoms.”

Kessler said the full range of effects from the pandemic are still unknown, but research predicts that isolation will cause detrimental ramifications on the adolescent brain.

“As much as we would all like to be finished with the pandemic, it is still ongoing, which impacts our ability to understand what has happened and how it will affect students long-term,” Kessler said. “It is predicted that it may function as an Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), a [common] category of traumatic experiences in recent psychological literature. The risks range from a higher chance of depression in adulthood, poorer cardiovascular health and shorter life expectancy.”

The stress caused by this traumatic experience puts students in a position where their main goal is simply to get through life, rather than truly living or experiencing it.

For Ruby Neuhaus (11), the monotonous structure of her life due to quarantine has put a strain on her ability to find joy.

“Isolation is really hard for me because a part of me is already struggling with mental health issues,” Neuhaus said. “In order to succeed, I need to have something to look forward to or have that celebratory feeling of accomplishing something. But being virtual, it’s hard trying to figure out something new to do, something to be excited for. [I think to myself]: How much of this stuff is really going to matter? I’ve honestly just started doing the bare minimum.”

This mindset is something that clinical psychologist John Rettger refers to as the “autopilot mentality.”

“The adverse impacts of being on autopilot extend across varying domains of functioning, including one’s thinking, one’s emotions, and one’s behaviors,” Rettger said. “One’s thoughts can become more negative [and] one may experience more negative or challenging mood states. One may also behaviorally withdraw—meaning, one may stop engaging in activities that bring joy, satisfaction, and happiness. This can lead to a vicious spiral toward things like depression and anxiety. Our view on life can also become more negative, pessimistic and hopeless.”

Neuhaus finds herself part of this vicious spiral where things that used to bring her happiness now just add more stress to her life.

“I used to love talking to people at school and it was so easy for me,” Neuhaus said. “Now, my social battery runs out, and talking to people I’m not close with feels like a chore. ”

Recognizing that Feelings are Valid

Many students, like Neuhaus, find themselves going through the repetitive motions to complete this school year. Rettger said that it is important to recognize this as valid because it is one of the many responses to the pandemic.

“[Simply getting through life] is a kind of emotional numbing and an attempt to cope with the adversities that are occurring,” Rettger said. “It can rob us of experiencing joy, happiness, creativity and vitality. There is no reason to ever judge anyone for feeling these emotions, as I think that they are natural responses to experiencing a pandemic and adversity. It is important, however, to still live through the high school experience and take steps towards transcending ‘just getting by.’”

For Nguyen and Neuhaus, staring at the faces of their classmates on their laptop screens allows them to acknowledge that this experience isn’t singular, making it easier to bear.

“Knowing that I’m not the only one going through this helps me feel less alone,” Nguyen said. “While there are times where I feel like I can’t get anything done, or I’m just overwhelmed with all that’s going on, I know other people are feeling the exact same way. In a way, we are all struggling together.”

While students may feel connected through this common struggle, many have not fully processed the trauma accompanying the pandemic. Kessler said it’s important for students to acknowledge this trauma and find ways to cope with it, despite it being natural for people to hold onto what they expected, planned for, or wanted in life.

“Wishing for a typical, in-person high school experience is what most high school students are wanting right now,” Kessler said. “This happens because it is painful to grieve what is lost and that pain is real. It can feel scary to feel the emotions of grief and yet avoiding comes with a different type of pain. It is a severe type of kindness and care you give yourself when you can release your grip on what you wanted to have happened and open to the reality of what is happening. It may feel like things are falling apart, but it gives you the opportunity to respond to what has remained.”

Reframing Negative Mindsets

To Neuhaus, planning out her week and writing down things to look forward to help her feel organized and prepared in a time where everything seems to be falling apart. While this approach works for Neuhaus, Lajiness said that there are many ways to cope with something as traumatic as a pandemic.

“The way that everyone reacts is not a one-size-fits-all,” Lajiness said. “The thing that I think is most important, though, is instead of wearing a pair of dark-tinted sunglasses and just seeing everything as gray and dull and sad, we can change our perspectives by putting on clear sunglasses with a rose-colored tint. We can ask ourselves, am I able to see things differently? [We can] think about things in a different way, feel things in a different way, which [can] lead to a new way of reacting to the situation.”

To do this, Lajiness described a tangible ecotherapy practice called Five Senses Grounding that can be done to ease stress or change one’s perspective on their current situation. Whether it be on the sidewalk outside your house, or on a nature trail, Lajiness said that practicing gratitude for one’s environment can help them feel more connected to reality.

“The way that I do it is by taking deep breaths and then finding five things to look at,” Lajiness said. “What can make this especially powerful is going beyond the surface level stuff. So [looking at] textures and movements and colors and shades and that kind of thing. [You can focus on] different colors of the leaves, how they’re fluttering in the wind, even light coming through them. I think a lot of people sometimes need help connecting with [their environment], finding the things they’re grateful for. To get outside, to do a couple of deep breaths helps activate the parasympathetic nervous system and calm the body down from anxiety or overwhelming feelings.”

Nguyen said that by going outside and looking at the cars passing by, she realized that the pandemic is a collective experience. In understanding this, Nguyen found gratitude in the fact that she isn’t alone during this time. Now, instead of moving along from day to day, Nguyen decided that she had the power to actively change her negative experience in quarantine.

“I decided to start doing things that made me feel better,” Nguyen said. “When I find myself losing motivation or hope, I take a step outside, see the cars driving by and remind myself that I have the power to turn this negative experience into a positive one.”

![Jolie Baylon (12), Stella Phelan (12), Danica Reed (11), and Julianne Diaz (11) [left to right] stunt with clinic participants at halftime, Sept. 5. Sixty elementary- and middle-schoolers performed.](https://wvnexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_1948-400x600.png)