I had a plan for my last summer before stepping into the grueling, horrific cloud of stress that I’d been forewarned is high school: I was going to get back into sports. It hadn’t been a priority for me previously, as I was perfectly satisfied with my 11-year-long tradition of Friday taekwondo lessons, but suddenly, the three letters CIF—or the absence of them—stripped my precious martial arts of its place in the conversation of bona fide sports.

In the very beginnings of my athletic career, I participated in volleyball, soccer, and tennis in several different sports camps and on teams. But, what about trying something new? Should I partake in my friend’s new favorite game of golf? Or, should I don a new pair of skates in a roller hockey arena?

Despite the novelty of golf or roller hockey, it felt like there was no world in which I could try out for a team without experience; my only options were what I had previously excelled in and could now cram to remaster.

After a long inner monologue that stretched from March to June, I decided to take up volleyball once more. I signed up for the same camps I’d taken in middle school, where I’d made wonderful friends I still adore today. I found myself excited … until I was placed on a court. Of the 14 teenage girls I was grouped with, less than half were there to have fun. The intensity of the others’ dog-eat-dog mentality weighed me down; I have always been a competitive player, of course, but it was only then that I began to see the game as a competition in which my performance had to be unprecedented.

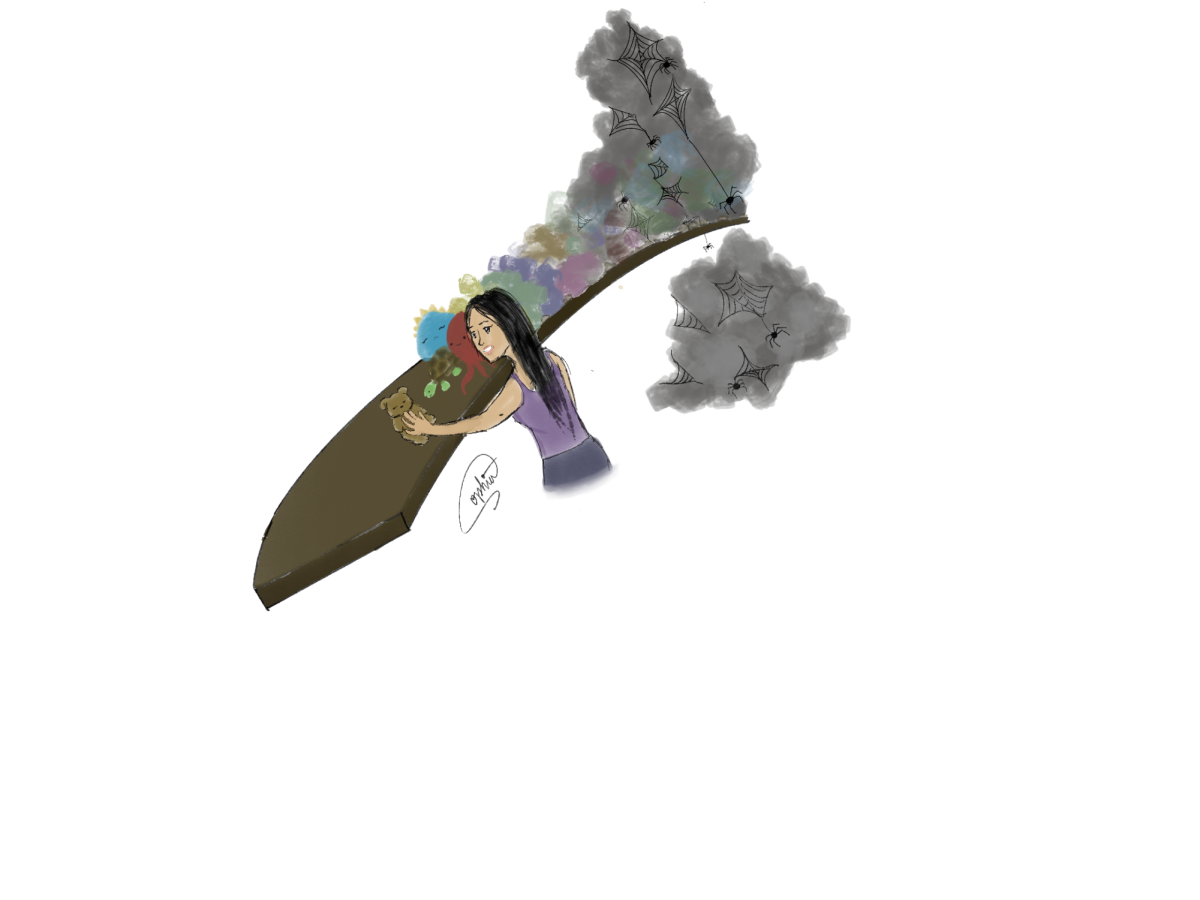

My frustration and accumulated stress from each minuscule mistake I made was rooted in the looming threat of high school tryouts. I’d chosen this sport—it was my sport and if I wasn’t flawless, it wouldn’t be mine any longer.

When I was a child, I’d enjoyed being on teams of most every sport known to man the way people enjoyed casual crochet club or art classes, and now I was dreading practice, horrified by the very thought of imperfection.

During one of these harrowing practices, I realized that my new affliction was not just a passing worry that a spot on the team would resolve: plainly, I didn’t like volleyball anymore. I didn’t like any of the other sports I’d considered either.

I wanted to be a part of any and every team; I wanted the glory of a place on one, the pride of a letterman jacket, a photo in the office, or so I thought. In reality, I didn’t really want any of it.

Sports, whether they are classified as CIF or club, are extracurriculars, and therefore voluntary by definition. However, it had been instilled in me by coaches and teammates that high school sport careers affect social status, both on-campus and off. Even in the atmosphere of middle-school teams, any mention of a sport was followed by You’re going to try out for varsity? For me, this cast a shadow on sports, painting varsity as an indomitable, daunting new world while failing to note that at its core, a high school sport is just a sport, and a high school team is just a team.

This is not to say that student-athletes should not be recognized for their work, but simply that this mindset framed sports to be work, the opposite of what I was looking for. The competition fostered by high-stakes tryouts is the spirit of all athletics, but I was allowing it to mold sports into a chore, rather than a passion.

Through my summer endeavors, I have found that, as with anything, it is important to put my goals and fears into perspective. We freshmen can get caught in whirlpools easily because we haven’t yet learned to swim. This tunnel vision is precarious—I want my high-school experience to be about trying new things, discovering new facets of myself, and having fun.

Therefore, through this venture, I have chosen to reframe my mindset and continue to broaden my horizons in sports to better myself, and for no other reason.