If you’re an integrated member of modern society, you’ve likely seen Mean Girls. You may also recall one of its most famous scenes, in which protagonist Cady Heron declares that “In girl world, Halloween is the one night a year when you can dress like a slut and no other girls can say anything about it” before showing up to a Halloween party dressed as an “ex-wife.” Despite her macabre garb being perfectly on theme, her entrance is met with disdain, if not outright repugnance, from her peers-–girls and boys alike. Although the movie is a well-known satire, the sentiments expressed in that scene are largely reflective of how society views Halloween costumes, particularly those for women: meant to be sexual.

The characters and occupations that these costumes portray aren’t inherently sexual. Often, there’s nothing sexual about them whatsoever. Take Freddy Krueger costumes, for instance. Freddy Krueger kills people while they’re dreaming and looks horrific while doing it. Naturally, he makes for a fantastic Halloween costume composed of his iconic features: a brown fedora, metal-clawed hand, striped shirt, and blistered skin covering his face. Men’s Krueger costumes reflect that: the clothing is as it appears in the films and uses a mask to recreate his deformities.

Women’s Freddy Kueger costumes are a different story. The search results yield costumes that are a far cry from the movie: striped minidresses with low necklines and dangerously placed rips, fishnet stockings, high heeled boots, and, most notably, little to no scarring. Instead, the models have full faces of makeup.

This pattern pervades nearly every other costume: cops, superheroes, zombies, and everything in between. In a study published by Erin Hipple, a social worker who spoke about Halloween sexism on ABC’s Nightline, approximately one third of costumes marketed to girls were sexualized to a degree. Less than one percent of boy’s costumes were, 11% of men’s costumes marketed to adults were sexualized, and for women, more than 90% of them were. Furthermore, while more than 33% of men’s costumes had masks that covered their faces, only 1% of women’s costumes included them.

The sexism isn’t only present in the costumes women and girls are offered. It’s also glaring in the costumes that they aren’t. Go to any storefront or website selling Halloween costumes and find the men’s or boy’s costume section. Some of the easiest costumes to find are job-based costumes, superhero costumes, and gory, monster-based costumes. Enter the women’s or girl’s section and finding those costumes becomes much harder. Instead, princesses, animals, and perhaps a sequined witch comprise much of the shelves. For girls’ costumes, occupational jobs are mostly restricted to historically female-held positions, like waitresses and nurses. Not only do these reinforce stereotypical gender roles for women, they also discourage men from entering “effeminate” fields or having “girly” interests.

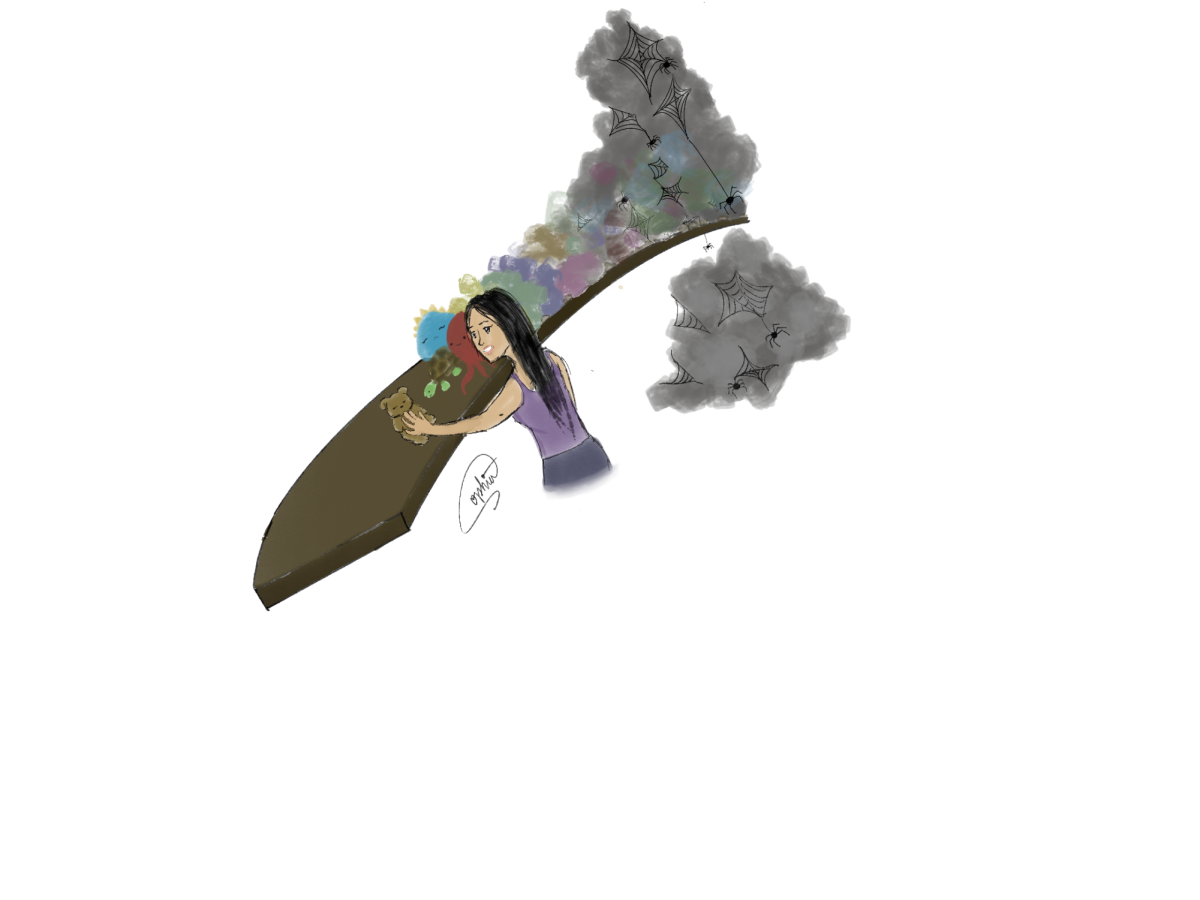

None of this is to say that women, or men, shouldn’t be allowed to wear sexual Halloween costumes if they choose. Part of Halloween’s peculiar, bewitching charm is that, through costumes, people can express themselves in any way they please. But when women and girls are denied the opportunity to express themselves in any manner except a sexual one, and all they see other women wearing sexual costumes, it’s a limit they internalize, and it boxes most of them in without them even realizing it. Women are more than their bodies, and to reduce them to benign, physically pleasing objects is to invalidate their depth. We deserve the same diversity of costuming as men, and the costume industry has a lot of redesigning to do.

Fake blood, prop weapons, and a zombie football player might get some shrieks, but a girl convinced that she needs to wear a miniskirt and a plunging v-neck to be a killer clown? Now that’s scary.