Curiosity has long been a driver of progress for the benefit of humanity. It significantly enhances a person’s ability to learn, acting as a catalyst for discovery and innovation. However, studies show that students experience a steep decline in curiosity and exploratory behaviors as they age, which has been correlated to changes in the way students are taught as they enter middle and high school.

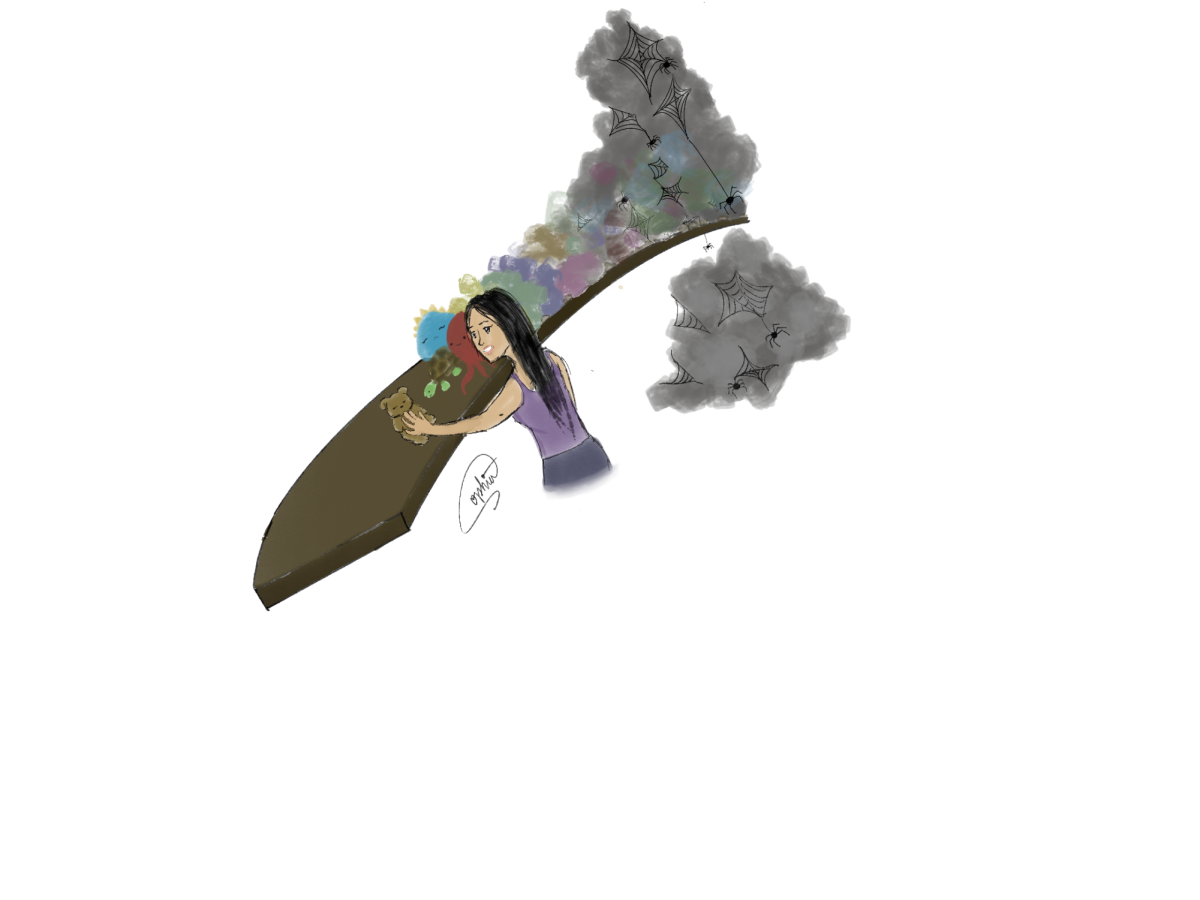

As they age, students adopt a culture of complacency, cultivated by the standard A-F grading system. This system unintentionally imposes ceilings on curiosity, and therefore, on learning. As Chester Finn Jr., former United States Assistant Secretary of Education says, “The traditional grading system is not aligned to learning outcomes.”

Children in preschool have unmatched learning abilities, which is partially attributed to their innate tendency to ask an exorbitant amount of questions. According to Paul Harris, a Harvard child psychologist, children ask about 40,000 questions between the ages of 2 and 5. A study by the University of Washington also states that kids’ brains are constantly connecting stimuli or thoughts. And as they’re making these mental connections, they’re seeking more information and clarification by way of questioning. In short, they are constantly improving their ability to think critically and perform complex mental maneuvers by asking questions, because their brains are in an expansive, highly connective mode. To them, there is no ceiling to knowledge.

However, as time goes on, this questioning behavior decreases significantly. A Newsweek report on the creativity crisis notes that by the time they reach middle school, children “more or less stop asking questions,” making them engage much less in school

Hebrew University suggests that the A–F grading system and high-stakes testing culture dominating most schools is largely to blame for this drop in questioning. As students start middle school, they grow accustomed to doing what it takes to get the grade, and nothing more, often losing the zest and curiosity that initially drove real learning.

Studies by Butler, Crooks, and Pulfrey have found that rather than stimulating an interest in learning, grades primarily enhance students’ motivation to avoid receiving bad grades, depleting their intrinsic motivation – their natural desire to learn for its own sake – and replacing it with extrinsic motivators like fear of failure or desire for rewards. Additionally, studies have found that, when in between grades like a C or a D, students are no more motivated to study for an exam than a student in the middle of the C range, invalidating a major argument proposed by proponents of the A-F grading policy.

This is by no means to say that evaluation in the classroom is wrong. Assessment, in fact, is key to learning. As Dr. Denise Pope, cofounder of Challenge Success and senior lecturer at Stanford said, “Assessment is feedback so that students can learn. It’s helping them see where they are and helping them move toward a point of greater understanding or mastery.” A B on a report card, by contrast, represents a stopping point; it is the end result, not a measure of lifelong progress.

A learning system where students pursue a constantly moving target rather than a stagnant letter grade incentivizes students to continuously strive for improvement, thereby asking more questions and developing more curiosity to reach that changing standard. There is no longer the imposed “ceiling” of an A, nor the rock bottom of getting a bad grade and giving up.

These organic teaching methods are already implicitly employed in classes such as Journalism 2, where students feel as if their writing capabilities have improved significantly more compared to a standard, structured writing class. In this class, students turn in their writing to be edited. After going through an initial round of edits, they make corrections and the article is passed on to more editors to receive further constructive feedback. This corrective system where papers are not given a letter grade, paired with a classroom culture that makes students want to improve themselves and ask questions rather than feeling forced to, is what allows learning to breach shallow understanding.

A learning system where students pursue a constantly moving target rather than a stagnant letter grade incentivizes students to continuously strive for improvement, thereby asking more questions to achieve that. There is no longer the imposed “ceiling” of reaching an A and feeling complacent with results, or getting a bad score and giving up.

At the end of the day, students will get what they put into their education. It is the job of the learning system to continuously push students to develop long-term curiosity, initiative, and joy in learning – traits that mark a truly educated mind.