On April 10, 1989, President George H.W. Bush signed the Whistleblower Protection Act into law. Effective immediately, government employees who made allegations regarding legal violations, misconduct, misuse of funds, public safety crises, and abuses of authority could not be fired or otherwise retaliated against by the agency for which they worked. Even threats of such retaliation were strictly forbidden. The act was heralded as one of the most influential pieces of legislation for governmental accountability and the well-being of the nation.

Rightfully so. Whistleblowers are heroes, willing to do the right thing even if it means placing themselves in danger or subjecting themselves to social ostracization. But the fact that this act had to be passed in the first place reflects a societal sentiment that I’ve always despised, one that has persisted throughout the ensuing decades. It’s all around us, although usually “whistleblower” is replaced by a more derogatory term: snitch.

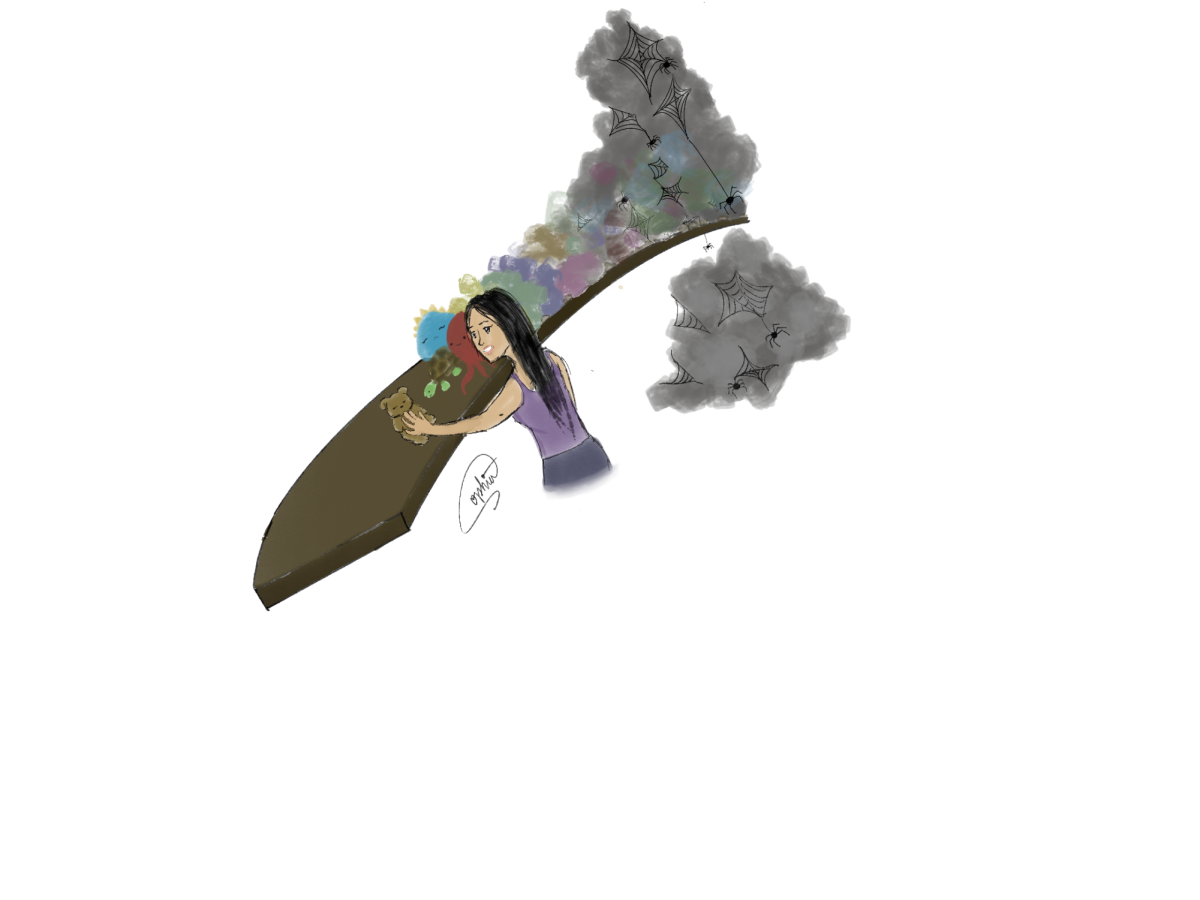

I’ve seen “snitches get stitches” play out all my life. I’ve been the snitch before, and felt the warmth in my stomach for reporting wrongdoing turn into a knot when people say I’m “innocent” “nosy” or “no fun.” Over the years, such labels wear down even those with the strongest resolve, until they start shrugging things off in favor of being socially palatable. It’s disheartening to see. I’ve made my peace with not being viewed as “cool” by everybody, but many people haven’t. For the most part, people raise as they are raised, and “snitches get stitches” has plagued social norms since long before any current teenagers, or even adults, were around. If silence equates to survival, no one is going to endorse the snitch lifestyle, and it’s difficult to blame them. We as a society have ourselves to blame for not doing our part to recognize the harm that sentiment has inflicted upon us.

Within adolescence and high school contexts, “snitches get stitches” is usually evoked in regards to “victimless crimes”, like substance abuse, academic dishonesty, traffic violations, etc.. The most common excuse given by defenders of the “snitches get stitches” mentality is “Well, it’s not hurting anybody else. They’re just doing it to themselves.” To which I say two things: 1) Who are we to determine that? 2) Even if that is the case, so what?

There is no such thing as a truly victimless crime. The idea that one person’s lifestyle choices affect them and them alone is simply wrong. Each and every one of us exerts influence on the people in our environments. When it is clear that wrongdoers aren’t going to be punished or corrected for their behavior, more and more people are inspired to take after them. Drinkers, drug abusers, and cheaters unchecked set a precedent, a very influential one. There are more tangible effects to wrongdoing as well. Drinkers start fights and crash cars. Smokers and vapers leave secondhand toxins everywhere they go. Reckless, helmetless e-bikers jeopardize drivers and pedestrians, as well as destroying public trails and green spaces with their tires. The academically dishonest ruin curves and push themselves ahead of honest, hardworking students. No one should be so presumptuous as to assume that bad things will self-contain themselves.

Let’s now operate under the assumption that someone is, in fact, hurting only themselves with their actions. Are we, as a society, really so apathetic towards others that we will let them self-destruct when we aren’t within the blast radius? Just because somebody is their own victim still makes them a victim, and it is our duty as moral human beings not to be bystanders enabling self-harm. Mature, socially-responsible individuals don’t break the law or commit serious transgressions. Mature, socially-responsible individuals think about the consequences of their actions in the present and down the road. If someone is compromising their own well-being and doesn’t bring it upon themselves to change their ways, others are not only justified in but morally obligated to say something. Just as it is presumptuous to assume that bad decisions are self-contained, it is presumptuous that the person somebody snitches on isn’t in need of outside intervention and won’t some day be grateful that someone had the courage to make them face the music.

We are not entirely without “snitch” role models. In school, all of us had “see something, say something” practically tattooed onto our gyri. In fact, when catastrophes are averted thanks to individuals who speak up, they are –– as they should be — celebrated, and labeled as “upstanders.”

On Jan. 27, a Rancho Bernardo High School student and his father were arrested after police searched their homes and found a stash of ghost guns, RPGs, and other weapons. It wasn’t an operation long in the works or connected to a large crime ring like one might expect from such a search. Student reports of concerning behavior and social media posts tipped police off. In this case, snitching saved lives.

What atrocities and tragedy their reporting prevented, we will thankfully never know. They’re not going to be called “traitors” or “stick-in-the-mud” for doing what they did. They won’t be told they should’ve “minded their own business.” But other kids, who speak up about wrongs they see, will. Snitches are only acquitted, if they ever are, after they’ve prevented something drastic and far-reaching from happening.

Let’s reflect upon the demonization of those who speak up. Snitches are the best and the bravest of us, and it’s about time they stopped living in fear of getting stitches.