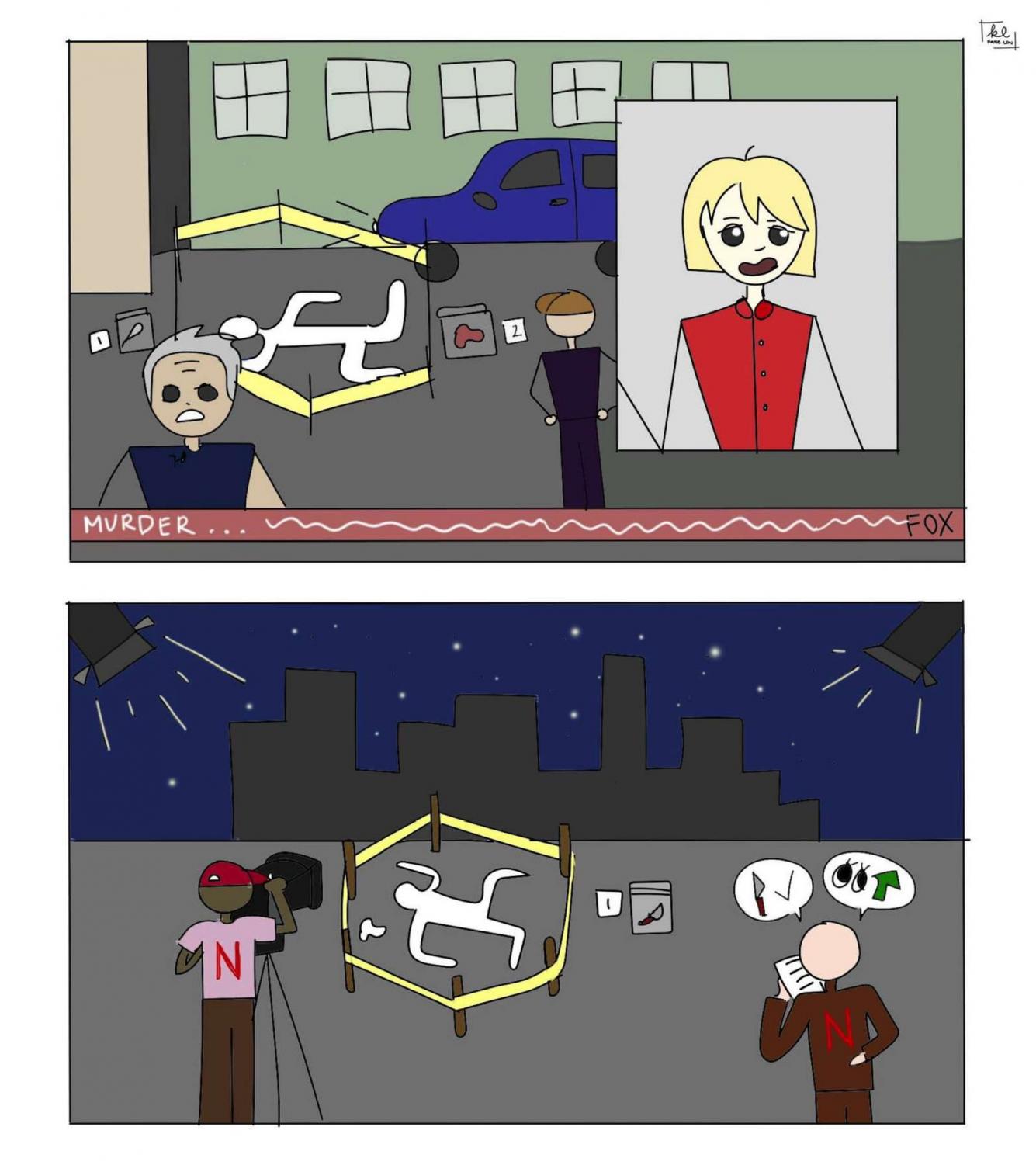

Opinion: The Problem with True Crime

March 11, 2021

Driving home from dinner, I mindlessly listened to a true crime podcast—like I so often do. It was the standard podcast format: as the hosts revealed details about an investigation into the disappearance of a mother of three, they engaged in speculation, made jokes, and advertised online goods and services. Out of nowhere I stopped and asked myself why I was consuming this deeply upsetting piece of media—and more importantly—why couldn’t I stop? The question nagged at me the rest of the way home.

Like so many of my peers, I’ve long harbored a somewhat morbid interest in true crime stories, but in order to enjoy them, I’ve had to completely divorce them from reality. These cases, even when portrayed through firsthand accounts and video clips, start to feel like fiction. And the more of them I hear, the more desensitized to them I have become.

For a long time, people have been fascinated with exploring the darker sides of humanity through true crime with shows like 20/20 and Dateline, but the genre really shot to popularity with the podcast “Serial” in 2014, which explored the disappearance and death of high school student Hae Min Lee. Since then, true crime media has been a staple in American culture. Society and Culture is the most listened to genre on Spotify, which includes true crime.

My introduction to true crime was through YouTube. Big names in the “True Crime Community” like Shane Dawson, Kendall Rae and Bella Fiori would tell stories of murder and disappearance—and my 12-year-old brain couldn’t get enough.

Because of my familiarity with many famous cases, Netflix’s recent influx of true crime content caught my eye. Netflix hosts more than 100 true crime documentaries and docuseries, more than a dozen having come out within the last year.

Most recently, American Murder: The Family Nextdoor, Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer, and Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel have been released as Netflix Original Series with great success. American Murder was especially troubling, as it revealed the personal text messages of the victim in the weeks leading up to her death, and showed video clips of her two daughters—ages 3 and 4—while describing how their father killed them. These murders took place in 2018. Documentaries like this are meant to captivate audiences, keep them on the edge of their seats wondering what will happen next with creative use of narration and home-video clips, or security camera footage, but what we consume for entertainment was someone’s real life and real pain.

In a 2018 Netflix original series (which is still running) called I am a Killer, producers did not get full consent from one victim’s family to share his story. Mindy Pendleton, along with most of her family, openly objected to Netflix sharing the story of her stepson’s murder in the season two premiere, but Netflix continued with the project, having gotten consent from a few of the victims family members. Even if families consent, the victim has no say how they are portrayed—and most people would not appreciate their death being used for entertainment. Victims cannot vouch for themselves after death, leaving private details to speculation, many of which victims would not want to be made public debates.

Along with true crime series exploiting victims, they sensationalize criminals in a way that people who are seeking attention—negative or positive— may find attractive. The prospect of being the main focus of a widely popular show or movie, and the publicity that comes along with that, may inspire future criminals. Especially seeing as heinous criminals like Jeffery Dahmer, Richard Rameriz, and Ted Bundy have amassed fan-bases of people who are particularly infatuated with them, or even find them attractive. Some of these “fans” romanticize the idea of being murdered so their death can be made into a documentary, invalidating the experiences of victims.

Worse than just giving killers attention, some shows glorify them, or make them sympathetic figures. Although it is interesting to understand the external and internal conditions that breed murderers, some shows paint cases in a light where viewers come away feeling worse for the killer than the one killed. An egregious example of this is a 2018 Netflix original series (which is still running), called I am a Killer. In the docuseries, Netflix interviews people put on death row about their crimes. The main voice being heard is that of the killer, humanizing them to audiences, whereas the victim seems like a far-removed—and therefore less sympathetic—character in their story.

True crime media can also harm suspects in unsolved cases by being selective with information in order to spin a captivating narrative. In the 2020 hit show Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness, production implies that Carol Baskin, a prominent figure and opponent to the star—proven criminal—Joe Exotic, killed her husband. Although a possibility, this is not proven, and since the airing of the show, Baskin has received hate mail and death threats as a result of this allegation.

So if this content is unethical, why do we eat it up? It’s natural for humans to be fascinated by things we can’t understand, and the fact that these stories are about real people brings on another layer of morbid excitement—“What if that were me? What would I have done?” The shock value of fictional crime shows like Criminal Minds is high enough to get millions tuned in, so when content is made with true stories, it’s even more personal and has higher emotional stakes, making it much more compelling.

Now, all of this isn’t meant to insinuate that if you enjoy true crime, you’re a bad person, or that the genre should be eliminated completely, but it is important to take a step back and examine the ethicacy of the content that we consume. Large media companies are only interested in making money, so it’s our job as viewers to hold ourselves accountable for what shows, movies, and podcasts we allow to gain popularity.