Opinion: Education on media literacy necessary to combat extremism, violence

January 21, 2021

We learn, early in elementary school, to tell the difference between fact and opinion. We are taught that the assertion, “Apples are fruit” is a fact and “Apples are the tastiest fruit” is an opinion. However, many Americans seem to have forgotten this simple lesson, leaving them unable to distinguish between the fact that the votes of November’s election have been counted (and recounted) to prove Joe Biden’s win and the fiction that seems to exist only on Donald Trump’s now-extinct Twitter page, that the election was fraudulent, that he is the rightful winner. Inexplicably, millions of Americans bought into Trump’s fiction.

The events at the Capitol building on Jan. 6 show the consequences of this inability to distinguish between fact and fiction.

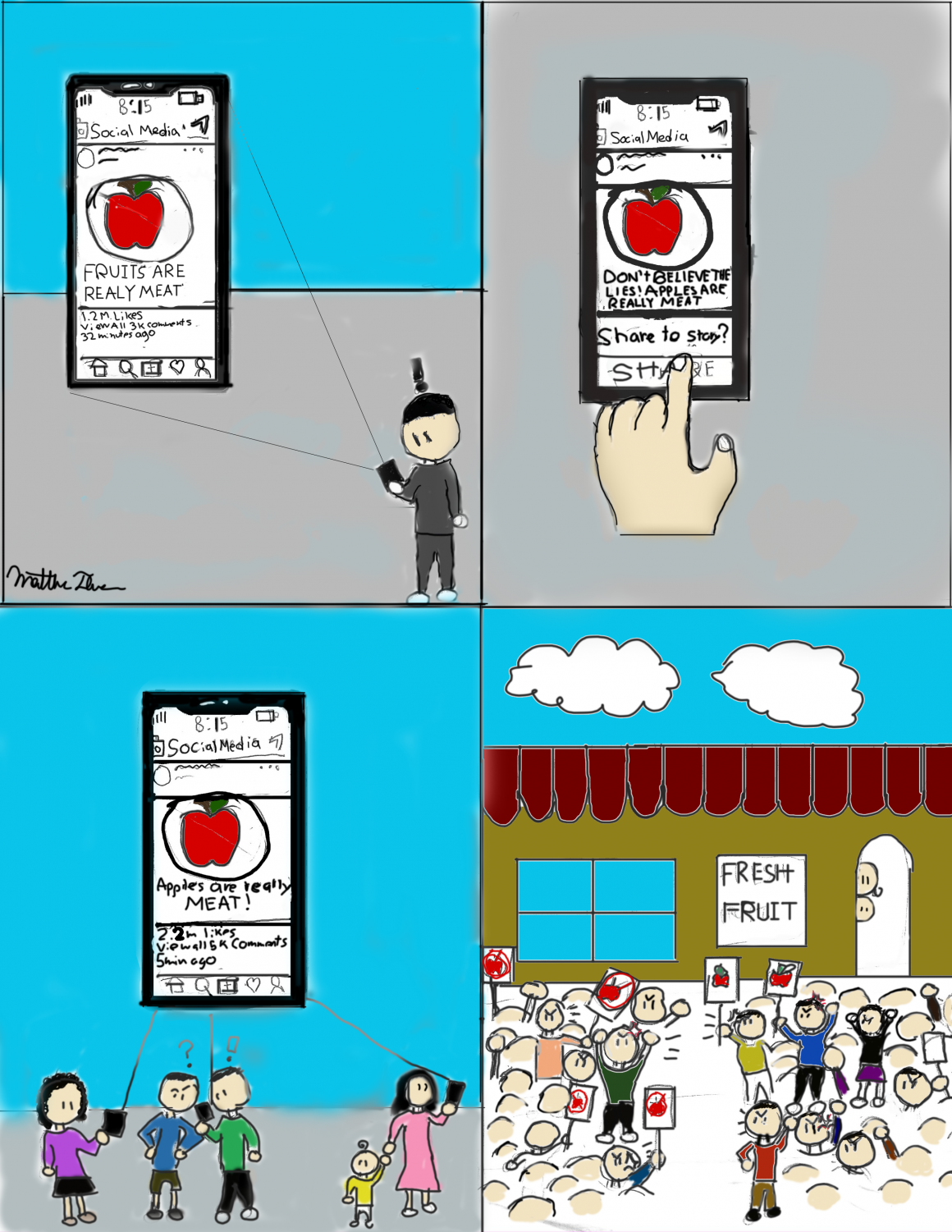

Those at the Capitol building were rioting on the basis of fictions propagated by social media. Yes, undoubtedly Donald Trump holds the most responsibility for the violence on Jan. 6—he was the one who tweeted ambiguously about a “BIG protest rally” to “Stop the Steal” on that date. Still, every user who liked or retweeted this, who allowed this tweet to gain even more popularity, holds a degree of responsibility. The riots made clear the immense power social media users—which is 70% of America—hold. Without the knowledge and resources to distinguish between fact and fiction on social media, Americans are making decisions that are feeding into violence, extremism, and a complete distrust in democracy.

This issue isn’t Democrat or Republican. It’s an issue of understanding lies for what they are, even when they’re coming from a news source believed to be trustworthy or an Instagram story that all of your friends have reposted or even the President himself. Until very recently, no social media users were responsible for the truthfulness of what they post. (And, now, even though Twitter and Facebook are taking steps to remove misinformation, some will inevitably slip through the cracks.) So it’s up to us, the consumers of information—the people who, though it may seem like we have only a small impact, decide what information rises to popularity on social media—to know the difference between information that is factual and information that is biased or, simply, incorrect.

Social media is not likely to go away any time soon, so it is up to my generation to improve it—because how Americans are currently using social media, clearly, is not working. I’m not saying, by any means, that every Twitter user is responsible for the events at the Capitol. But still, every Twitter user—or Instagram user or Facebook user or Snapchat user—holds something that can be a tool or, based on the riots, a weapon. It’s about time we start incorporating lessons into our high school curricula on safe ways to wield this weapon—teaching, again, the difference between factual and fictitious information.

Many argue that the purpose of teaching history, one of the core subjects in school, is to help students better understand and contextualize current events—but we can’t expect students to be able to do this if they never learn to understand what current events are real and which ones are fabrications. With extremist groups like Proud Boys and QAnon gaining more influence in America, students must learn how to separate the propaganda from objective truth. If schools want to counter this extremism, if they want to protect democracy, they must increase funding for news literacy programs.

The News Literacy Project (NLP), an organization that provides resources for schools to help educate on news literacy, defines the concept as: “The ability to determine the credibility of news and other content, to identify different types of information, and to use the standards of authoritative, fact-based journalism to determine what to trust, share and act on.”

According to NLP, 26% of U.S. adults surveyed could correctly classify all five factual statements presented to them, 35% of U.S. adults surveyed could correctly classify all five opinion statements presented to them, and 96% of U.S. high school students surveyed failed to challenge the credibility of an unreliable source.

These numbers are alarming, especially when according to an MIT study, misinformation spreads “farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly” than truthful information. In fact, in that study, the truth took six times longer than falsehood to reach 1,500 people. The main issue here is not that Americans are believing fictions they read online, it’s that they are sharing it too. And when shared with enough people, as we saw leading to Jan 6, misinformation becomes a rallying call for violence and extremism.

We need to educate the next generations of Americans in a way that can break these vicious cycles of misinformation and extremism. And the best way to do this is through news literacy programs, in whatever way we can implement them.

NLP provides resources for educators to teach lessons on topics like avoiding confirmation bias and categorizing online information based on its purpose. These are the sorts of lessons that need to be taught in our classrooms so students know how to intelligently navigate the ever-expanding world of online media. As Stanford History Education Group put it in their “Students’ Civic Online Reasoning” survey, “Education moves slowly. Technology doesn’t. If we don’t act with urgency, our students’ ability to engage in civic life will be the casualty.”