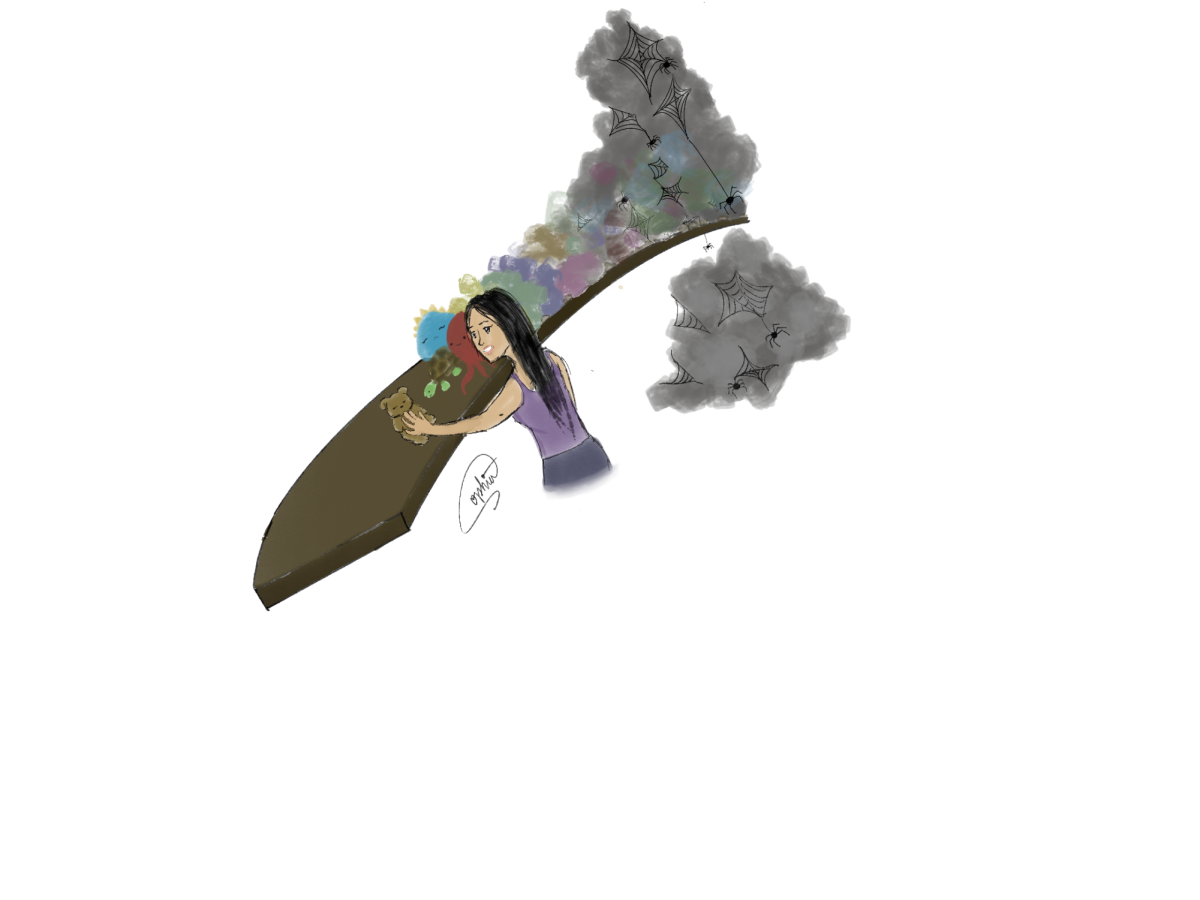

Today is finally the day. I know I can do it. A foe that has so long evaded me will finally meet its end. Its very existence has taunted me so, pervading my life, a constant in my thoughts and dreams. My enemy, the 766-page nightmarish novel, The Brothers Karamazov, torments me with its concentrated, convoluted text. I feel a slight tremble in my hand as I arm myself both mentally and physically. But, I feel confident in what I’ve chosen for the attack.

My weaponry of choice?

An expertly-crafted black 0.38 Muji pen, prepared to strike each and every page, till the very last.

I don’t know when I first began to wield this glorious writing instrument to ground me in the printed word, but for as long as I can remember, annotating books has always served as a way for me to better engage with the content I am reading. Especially in confusing 19th-century Russian texts, adding underlines and brief notes — some in the form of intellectual analysis, the majority in the form of raw, expressive reactions (curse words, a slurry of exclamation points and question marks, or even cursorily drawn shocked, happy, or crying faces) — has always allowed me to comprehend a text more deeply due to the constant attention I am forced to give it. Of course, it slows me down, but I don’t mind at all. The story feels more immersive this way, as the words seem to come to life, the rest of the world fading away, as I get caught up in its wondrous narrative. And, compared to laying in my bed and holding the book in front of me, getting lost in an ocean of complicated vocabulary, I am required to sit up and pick apart the novel word by word. It may seem less appealing to read this way, but the book is so much more enjoyable through my annotations, as it feels like I am having my own conversation with the author (that can sometimes get extremely heated and involve fully capitalized sentences).

In an experiment conducted in the “Journal of Research and Innovative Teaching and Learning,” scientists tested the learning comprehension of students who annotated history books compared to students who simply read the same content without making any notes. Their results found that annotating increased student comprehension of complex text, aiding them to visualize key points and slowing down their reading. Annotating truly makes me process and react to every individual choice that the author makes, giving each minor character, vocabulary choice, or even comma my full focus. Even in Crime and Punishment, when Fyodor Dostoevsky refers to the main character’s name with countless spellings, I can easily identify him because I am fully engrossed in his narrative. Through my margin notes, I am able to separate his distinctive personality and actions from the rest, allowing the book to flow better and my understanding of the novel to be much more satisfying.

Not only has annotating served to help me better understand the books I read, but it’s helped others as well. I recently started to mail my decorated books to my friend, as an appeal to try to get him into literature. He has said that my reactions and comments on the side have helped entertain him while reading, pushing him through the 496-page novel, A Gentleman in Moscow, a feat that he never thought he’d be able to accomplish (not that Amor Towles’ writing needs “pushing through,” it’s an absolute delight).

Therefore, I urge you to arm yourself with your favorite writing instrument and face a book that you have been scared to start. You’ll find it much more enjoyable and engaging, I promise!