The Hawaiian islands are known for their touristic draws: the clear turquoise waters of their beaches, the dense foliage of the jungle, and for the ubiquitous palm tree, swaying in the breeze.

The Hawaiian islands are known for their touristic draws: the clear turquoise waters of their beaches, the dense foliage of the jungle, and for the ubiquitous palm tree, swaying in the breeze.

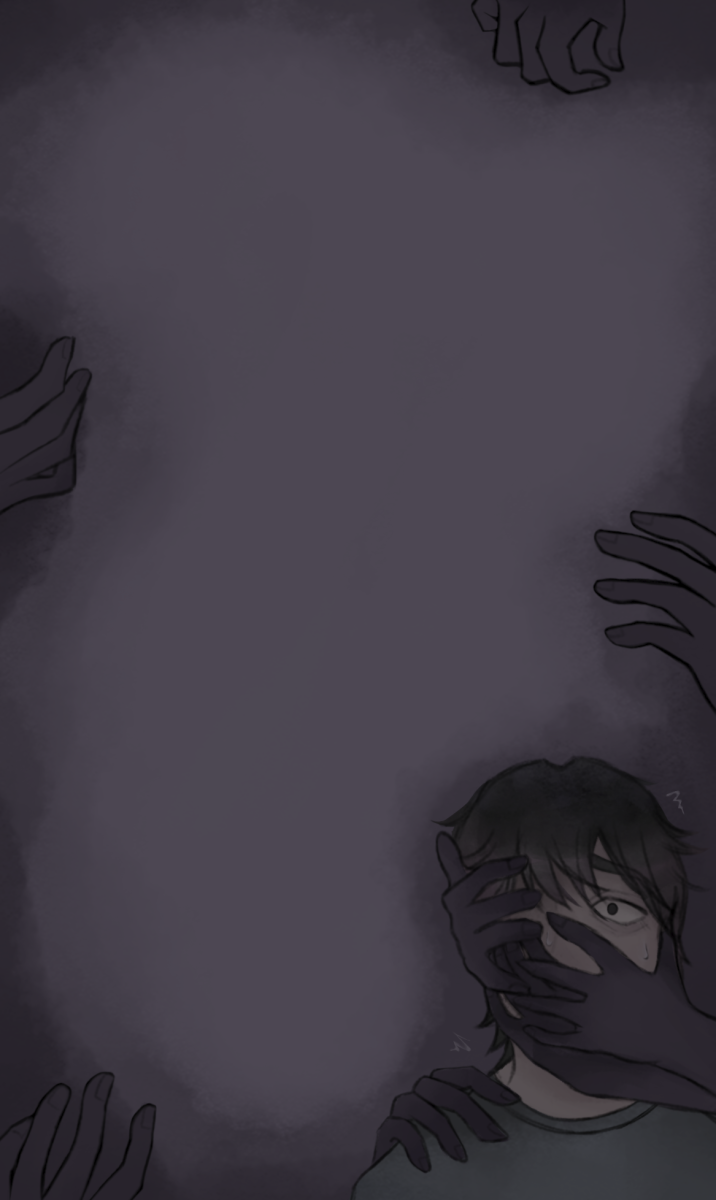

The truth, however, that Hawaii and its people have been exploited since the very beginning, is anything but picturesque.

Since the beginning, the United States government has been subversive with its intentions toward Hawaii. The overthrow of the queen by a group of mostly white men and plantation owners was done without the consent of the Native people, as was conceded in the 1933 Apology Resolution issued by the U.S. Congress.

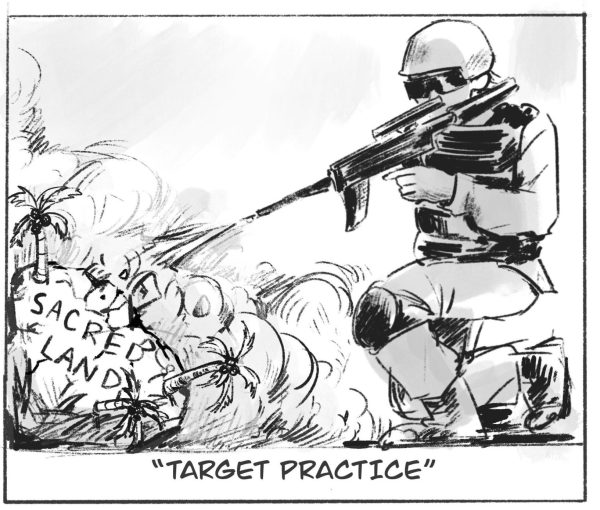

In its early days and still today, Hawaii was seen as a strategic outpost by the military. Most notably, the Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA), a 135,000-acre swath of land on the big island, is made up of mostly confiscated lands from the annexation of Hawaii. Of those acres, 30,000 were leased by the military in 1964 for a single dollar, to be used for the next 65 years.

This land, some of it sacred to Natives, has large tracts dedicated to target practice, being bombed repeatedly with little care for its cultural significance or the environmental harm that is done.

The PTA is not the only instance of this. On Kaho’olawe — a small island near Maui that was confiscated after the attack on Pearl Harbor — bombs and unexploded ammo can still be found even though it has been nearly 35 years since the military abandoned the installation in 1990. Despite a nearly $3 billion clean-up project by the state, 25% of the island is still not cleared of unexploded ordnance.

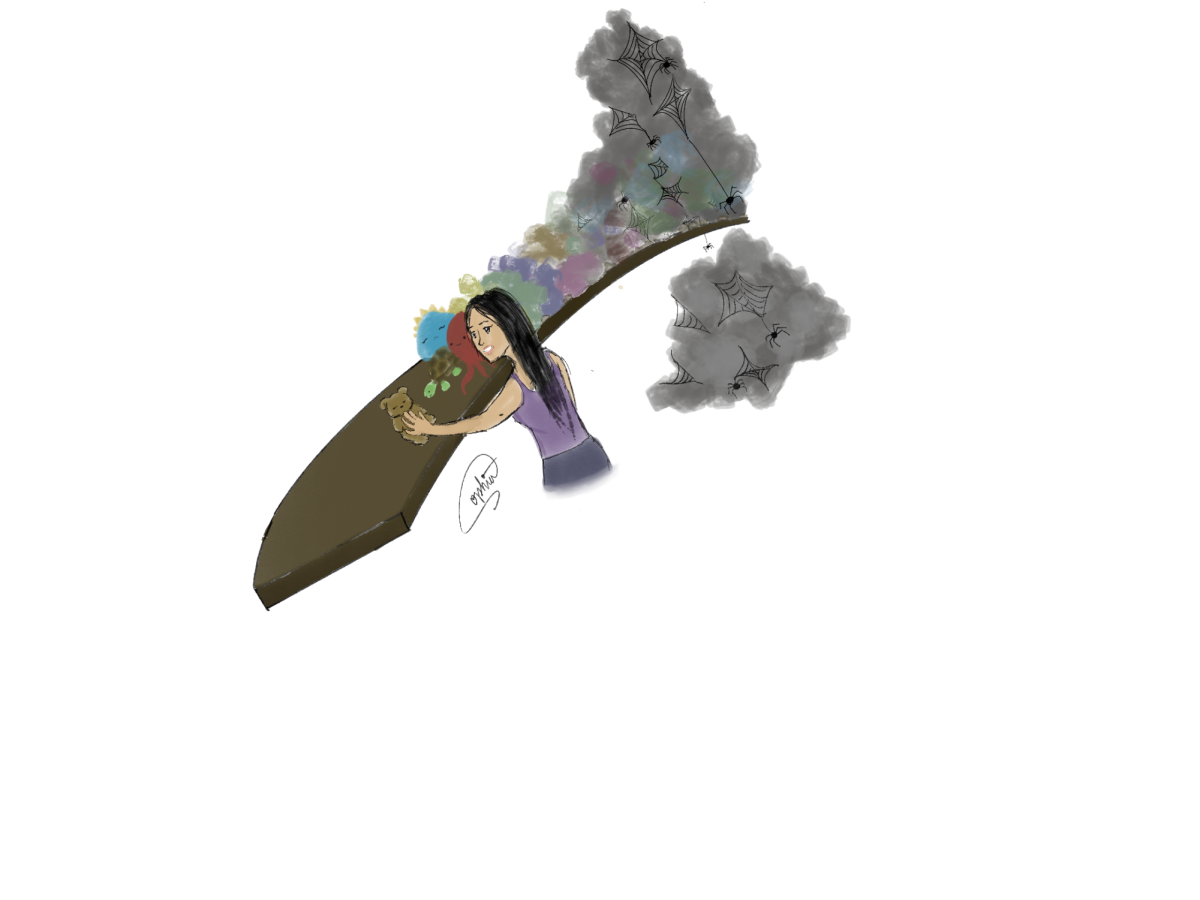

It’s not just the military that exploits the islands: the very systems of tourism that Hawaii depends on simultaneously strangles it.

The majority of tourism jobs are low-paying, which combined with the state having the highest cost of housing in the nation (149% above the national average), creates a large homelessness problem. Hawaii consistently lags just behind California, the nationwide leader, in rates of homelessness.

The Vacation Rental Unit (VRU) industry specifically is a damaging sector of the tourism system. These short-term rentals, which make up one out of every 18 housing units in Hawaii, take badly needed properties out of the housing market, while they often sit empty for a majority of the year. These rentals are usually owned by out-of-state residents, meaning that revenue from these properties generally isn’t funneling back into the state economy.

Food supply is another issue that the past colonization and current systems have put in jeopardy. Before the rise of sugar plantations and, later, pineapple farms created by white settlers, the islands grew the majority of their own food. Now, about 85%-90% of food is imported, contributing to a very high cost.

Combining this with the high cost of housing, and low-paying jobs, it’s no wonder that ⅔ of Hawaii’s population is struggling financially.

Now, I truly am not trying to make vacationers feel guilty about visiting the beautiful islands, as in reality, there is very little one tourist can do or not do to tip the scales either way. What is needed is reform at the government level, and a society-wide willingness to listen to the voices of those who have been silenced.

Some Native Hawaiians say to just not visit the island at all, and this is a good point, as it would drastically reduce those industries that have been systematically harming the state. However, given the fact that 21% of the GDP in an already struggling statewide economy comes from tourism, a dramatic change like this could do incredible harm.

Many propose that cutting down VRUs could help, and a recent law has been passed in the state that allows counties to create restrictions in this sector.

Aside from housing, the military’s 65-year leasing of land expires in 2029, and while they are trying to renew it, many activist groups oppose them, and if successfully blocked, could give land back to the natives who have lived there for generations.

In agriculture, promoting a diversity in produce grown on the island could help make food more affordable. Currently, the majority of produce grown on the islands is monocultural — the widespread sugar and coffee plantations are designed primarily to export foods for profit, not to provide for the locals. The state has laid out plans to encourage diversifying their crop makeup, but the goal’s end date is decades away.

Nothing about these issues are easy, their topics or their solutions, yet it’s necessary to notice and attempt to reverse this system of colonization and oppression that has spanned centuries.

![Jolie Baylon (12), Stella Phelan (12), Danica Reed (11), and Julianne Diaz (11) [left to right] stunt with clinic participants at halftime, Sept. 5. Sixty elementary- and middle-schoolers performed.](https://wvnexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_1948-800x1200.png)