By 2050, the world’s oceans will contain more plastic than fish. But I’m sure you know that already, or have heard something similar before. This fish statement, in particular, continues to circulate widely in media, social networks, and even among sources with high authority such as policymakers or renowned environmental organizations like the WWF (World Wildlife Federation). The reality is, though, that no research has ever reached this conclusion. No amount of statistics or mathematical predictions can estimate plastics up to 2050. We don’t even know how much plastic is in our ocean today.

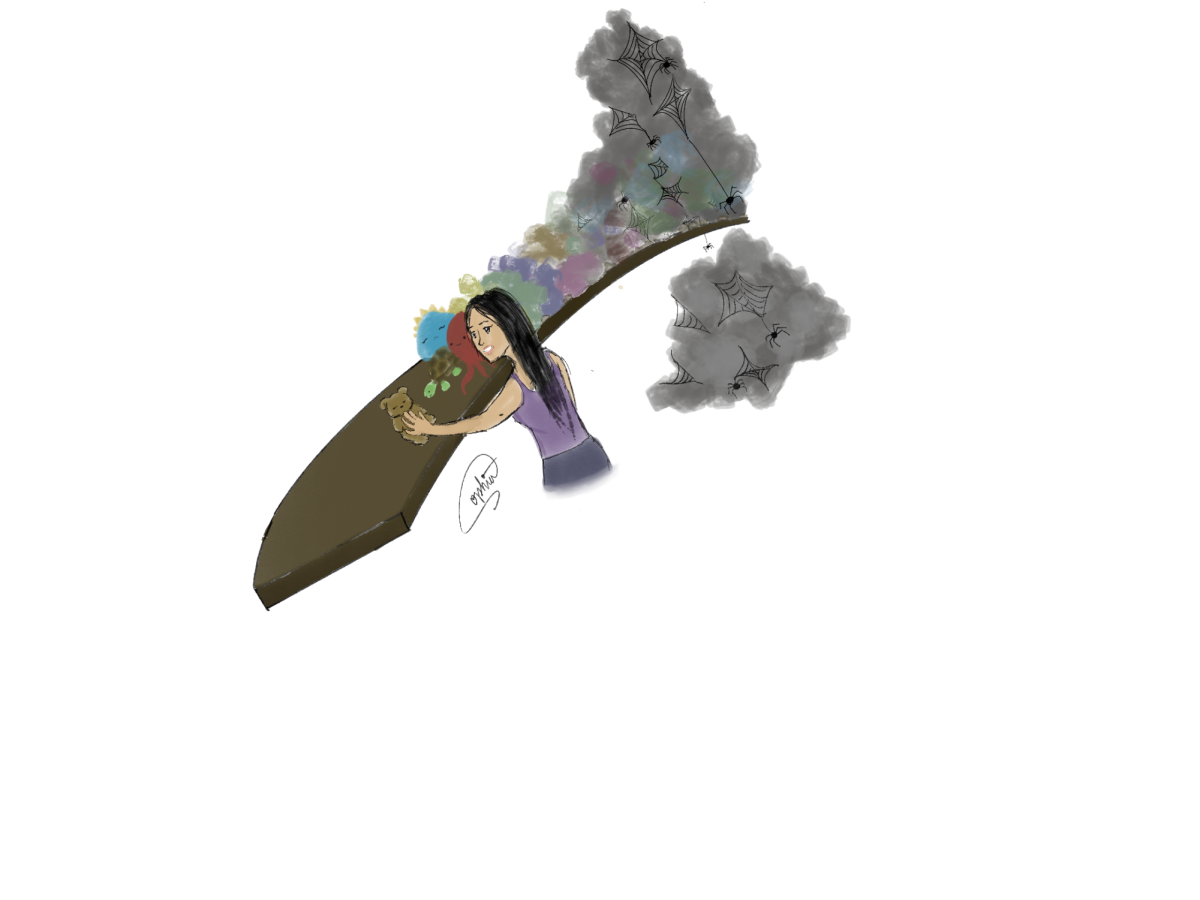

Environmentalists invoke similarly dramatic and overblown declarations for other problems as well: “There are only 60 years of farming left if soil degradation continues,”(Scientific American) or “We will see virtually empty oceans by 2048”(Science). No matter where we look, the sky seems to be falling. These statements reveal an ongoing trend in how we receive climate-related information — Cataclysmic messaging, big bold letters, and no source or academic article citation in sight. These motifs simply aren’t reality, and, rather than inspiring action, they inspire fear, hopelessness, and disregard for the very real problems at hand. Even worse, they incorrectly use words like “will” and “are,” denying the ability of humanity to take charge and create a better future.

For example, according to the media, since I’m younger than 60, I have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth — apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, catastrophic flooding, massive crop failures, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought. While these things could very well happen, saying it in such a definite way only makes these problems seem hopelessly inevitable when they aren’t, in fact, inevitable at all.

A PBS poll from 2022 found a 9% decrease in the number of Americans concerned about climate change’s impacts, a number that doesn’t align with the 299% increase in climate-related media coverage from 2011 to 2022. Even in my own life, I’ve observed an attitude of hopelessness from those around me, which is unavoidable considering the distressing information we are fed on an almost daily basis.

And, as an average person who has enough going on in their life, the hellish encroaching idea of climate change painted by media just gets pushed off to future me, or handed off as a job that only politicians or world leaders could solve. After all, if this is an inevitable event, then why even try to change it?

This is the problem with the way the climate crisis is presented to us. There is no thorough explanation or analysis or background given, just these flashy, apocalyptic, often misleading one-liners meant to garner attention or more interactions on social media. How did this problem start? How do we prevent this in the future? What can we do now to mitigate the issue? Answers to these questions are nowhere in sight. Instead of developing climate literacy, these statements just fuel climate denialism. As a result, we too often just accept the doom and gloom soundbites we encounter and just give up. If humanity is perceived as doomed, then the motivation to address climate change diminishes.

I used to experience this same existential hopelessness whenever thinking about climate change and thus opted to avoid thinking about it altogether. I believed that I could do nothing and that the future of the planet lay in the hands of world leaders. This changed when I attended COP29, the annual UN climate conference based around the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global warming below 1.5 ℃ by 2050. In recent years, COPs have been regarded as COP-outs, due to the disappointing amount of action being done policy-wise and the disregard of set goals. This aligned with what I saw at the conference in Azerbaijan last month. The global north listened and nodded enthusiastically while the global south begged for aid. Aged policymakers placed responsibilities and hopes on youth. Youth placed blame and expectation on policymakers. The funds raised were a trillion dollars short of the target. Nothing really got done.

What did amaze me, though, were the technologies being developed in various industries to reduce energy usage, water consumption, carbon emissions, toxic waste, and more. While governments dawdled, these engineers, scientists, and companies took it upon themselves to reduce their environmental impact, even if it was at the expense of their profit. Notably, Delta, a Taiwanese data center company, started a program to farm coral, restoring numerous reefs and ecosystems on their shoreline. Japanese companies worked on building carbon-zero buildings, implementing a circular economy in supply chains, and installing clear solar panels to maximize the surface area on skyscrapers. Researchers developed lab-grown meat to reduce the need for livestock and lower methane emissions

Hope lies in these industries. A common misconception is that individual actions, such as taking shorter showers or eating less meat are the best thing someone can do for the planet. Although those are steps in the right direction, the majority of global greenhouse gas emissions are generated by industries and large-scale commercial activities. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), around 70% of carbon dioxide emissions stem from just 100 companies worldwide. Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should all take hour-long showers and leave the lights on at all times, however, this knowledge enables us to shift our efforts to something that will result in an industry impact, something that will kill the problem where it originated.

That is our solution: to promote climate literacy from early on. Mandate at least a baseline of climate knowledge to be taught at schools. Make sure that everyone cares about our planet and is aware of the state it is in and the state it will be in without immediate attention. After all, these children are the entrepreneurs, scientists, policymakers, and leaders of the future.

The IPCC, tells us that, to limit the rise to less than two degrees (often referred to as the point of no return), we not only need to reverse the trend of the past three decades, but we also need to approach zero net emissions, globally, in the next three decades. By providing a plausible and easily actionable goal instead of scaring people with apocalyptic visions, we can make real strides where policymakers refuse to.