Yes

Zeina Nicolas

I couldn’t tell you the number of times I’ve been in class and could see someone near me on their phone playing a video game or scrolling on social media. Whether during a lecture, lab, or solo work time, the draw of digital distraction frequently succeeds in di- verting adolescent attention away from the schoolwork at hand. Now, enter a solution several teachers have

begun to implement to remedy this crisis of active presence: the phone jail.

Granted, some students probably look with horror upon this contraption de- signed to keep them from their beloved devices for an hour and a half.

However, this agent of control is a necessary evil and

should be adopted more widely.

Research shows that smartphones decrease students’

capacity for learning. In a 2023 study conducted at Pa- derborn University in Germany, researchers found that the mere presence of a smartphone decreased people’s working memory capacity and fluid intelligence (abili- ty to solve novel reasoning problems), leading to lower attention.

This is only one of many studies that support this phenomenon. In classrooms, teachers should not be battling smartphones for their students’ attention — that battle will usually end with a victory for the phone and a loss for both teacher and student.

In cases where the teacher is not actively lecturing, the use of smartphones in class decreases the amount of effort students put into talking with their peers and forming connections. Although I make this claim based on my own observations, this phenomenon is also em- pirically supported: a 2012 experiment conducted at the University of Essex in the UK found that when strangers were put in a room together and had a con- versation, subjects reported feeling less close to their new acquaintances and having lower relationship qual- ity when there was a smartphone present in the room.

If people fail to connect when phones are close to them, removing the presence of those phones would do wonders to foster the social connections that benefit us all.

A hanging phone holder with numbered pockets 1-36 sells for $14 on Amazon. This is a small invest- mentforaschoollikeWestviewtomake,butthere- turn on that minor investment could do so much to im- prove the quality of life in us students as our attention is not constantly drawn, at least in part, to our phones.

No

Phoebe Vo

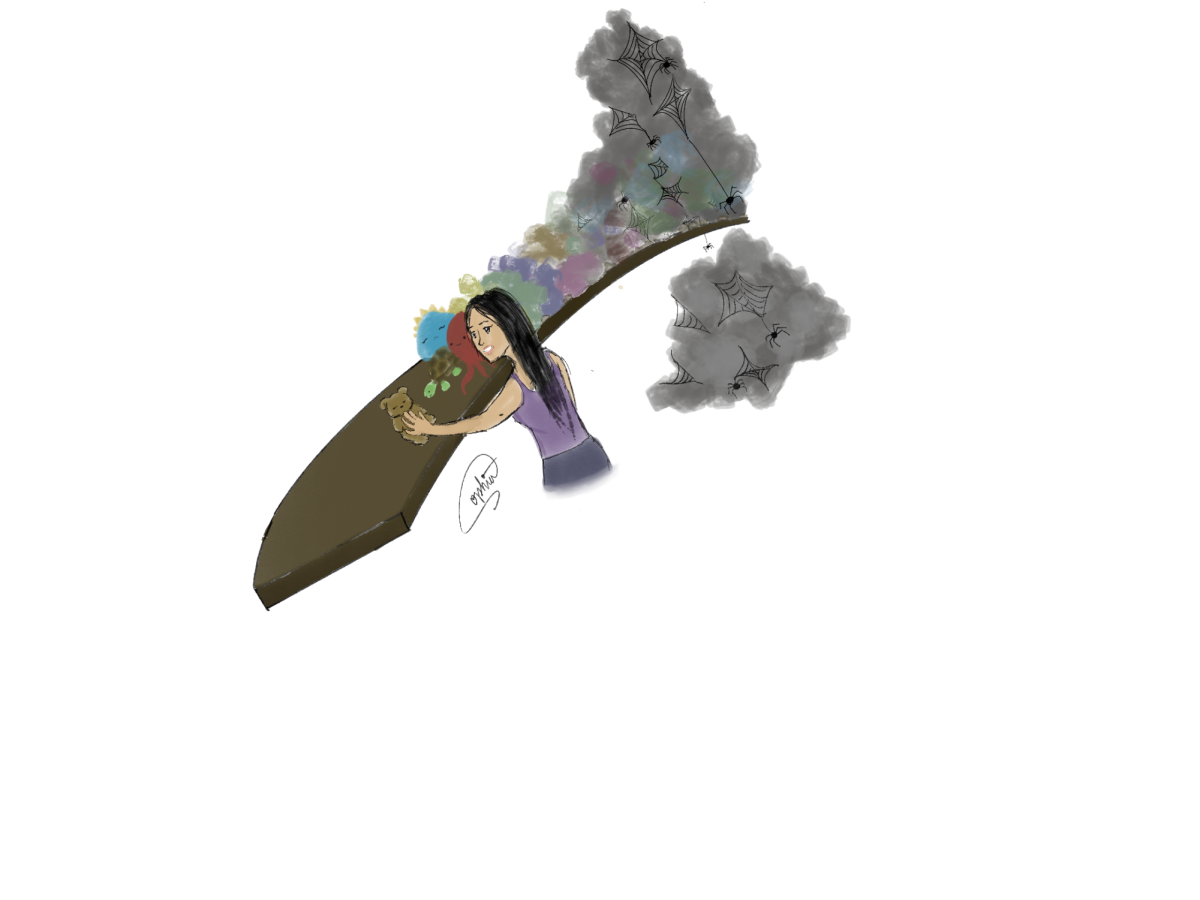

Waltzing through the door of APEL one day in ear- ly January, I caught my friend shaking tremendously, their eyes wide with unspeakable horror, as a singular finger motioned towards a new addition to the classroom.

As I turned to the object of their dread and fear, my face immediately went grim. Paralyzed in a state of shock, the most vile of evils stood before me: a phone jail.

I had heard rumors of its ghastly appearance before, but never did I think it would worm its way into my classes. And ever since that fateful day, the phone jail has been on full display in L-104.

My vexation with the phone jail isn’t its purpose. I understand the need for it: students are distracted by the allure of their glowing phones. I’ve witnessed it firsthand and I feel great sympathy for teachers who have dealt with such behavior as well as students who are held captive in their screens.

But, a phone jail? It’s archaic, to say the least. This beastly thing, with its patronizing numbers and individual phone slots, looks down on me as if I was just some common elementary school child. Is this really the best solution for this age group? No, it isn’t. High school acts as a transition into adulthood, where we teach students responsibility and how to set their priorities straight. Being able to make those decisions themselves is a skill that our classes and our community should teach. A phone jail may have worked in middle school, but we are far past that now.

In fact, an extensive study in 2003 by John Marshall Reeve, Glen Nix, and Dianae Hamm, titled Testing

Models of the Experience of Self-determination in Intrinsic Motivation and the Conundrum of Choice, dis- played the importance of a student’s internal locus, volition, and perceived choice in a classroom.

Their study revealed that these three aspects are deeply correlated with one another and that environments that facilitated a student’s autonomy and individual choice increased their motivation and self-determination.

We need to foster this kind of mindset in our class- rooms to truly solve the phone problem, rather than having a solution in the phone jail that isn’t sustainable for the future. I’m aware that there might be short-term value of the phone jail to limit distractions, but it could come at the cost of creating responsible members of society that will soon exist outside of just the classroom.

We, at one point, will have to stop treating high-schoolers like children. In college or future workplaces, there won’t always be a phone jail to help you control the urge to play on your phone. Stu- dents will have to owe up to their actions and allow their self-control to come from an internal place.