PUSD effort to combat chronic absenteeism brings improvement

June 2, 2023

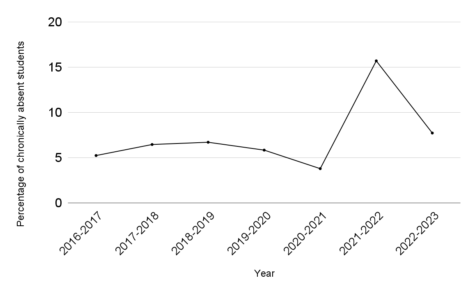

Since the return of in-person schooling in a post-COVID era, chronic absences have risen dramatically in Poway Unified School District (PUSD), more than doubling to a rate 15.69% for the student body in 2021-2022 districtwide. Prior to COVID, the district average fell around 6%. This data was reported at a PUSD Board of Education meeting, April 6.

Since the return of in-person schooling in a post-COVID era, chronic absences have risen dramatically in Poway Unified School District (PUSD), more than doubling to a rate 15.69% for the student body in 2021-2022 districtwide. Prior to COVID, the district average fell around 6%. This data was reported at a PUSD Board of Education meeting, April 6.

In response to this rise in chronic absences, PUSD’s Director of Student Attendance and Discipline Jamie Dayhoff and Administrator of Student Attendance and Discipline Priscella Sanchez worked to reinforce the Chronic Absentee Intervention Plan (CAIP) throughout the past two years. Since then, chronic absenteeism rates have dropped to 7.71% in the 2022-2023 school year.

“The big change that PUSD has done so far is to move away from more punitive measures, such as automatically sending a student to the School Attendance Review Board (SARB), and instead to use the CAIP, which is a lofty, four-page list of interventions,” Sanchez said. “With that, it really tries to address four different barriers for chronic absenteeism through the [student’s] social-emotional need. The [CAIP] tries to identify what specific challenge or social-emotional behaviors each kid has, and it’s different for everybody.”

Although the CAIP had always been an existing course of action, Sanchez said staff has worked to make it more accessible to all students and not just those with Individual Education Plans (IEPs) and 504 plans, which are typically exclusive to students with special needs or learning accommodations.

“We’ve opened up [intervention plans] for the past several years to everybody, so they don’t necessarily have to qualify for special education or have a document of disability and a 504 plan,” Sanchez said. “Oftentimes, as we know, our kids, who are not yet identified as having a social or emotional need, need those resources.”

Through the CAIP, staff on campus and from the district can help pinpoint what struggles are keeping a student from attending school.

“In years past, what may have happened is the student gets a referral to the county but doesn’t really get their social-emotional needs met,” Sanchez said. “Now, we’re looking to identify four different avoidant behaviors [ to] determine a student’s function of behavior. Do they need extra attention? Are they avoiding something at school specifically? [There] could be avoidance specifically just to academics. Is it also school avoidance because of social reasons?”

On top of an augmentation of the CAIP, Sanchez and Dayhoff have trained principals to properly communicate with staff members at schools in order to support students who exhibit chronic absenteeism.

“Sometimes, a conversation happens with a counselor, sometimes it’ll happen with the assistant principal, sometimes it’ll happen with teachers, school psychologists, and the Mending Matters therapist,” Sanchez said. “Consistently since September, Dayhoff and I have been training all the groups just mentioned and we’re saying the same things on repeat: it’s all hands on deck; everybody needs to be a part of making sure this student feels connected back on campus.”

In certain cases, Sanchez said students who are unavailable due to being out of town or going through a traumatic event can be offered an Off-Campus Independent Study (OCIS) contract, which typically lasts for 14 days. In an OCIS contract, teachers will have agreed to put together a packet of work for the absent student with the necessities.

“What we’re doing differently to help mitigate chronic absenteeism is using OCIS contracts more,” Sanchez said. “It doesn’t have to [just] be because the student is out of town or they’re leaving for something they have to attend. If they’re chronically absent and we know [the] specific reason why—maybe they’re depressed and anxious, maybe there is a recent divorce—oftentimes we’ll [say], ‘You’re human. You’re normal. You need to feel okay first before you can focus on calculus and chemistry.’ [The contract] is just to keep their grades on track so it’s not so overwhelming and you’re not dug in this big hole that you can’t get out of.”

According to Sanchez, when addressing Youth in Transition (YIT), which focuses on students and families who don’t have a stable home, administrators, school psychologists and counselors take a very trauma-informed approach to carefully handle families who may feel shame about their situation.

“Sometimes they’re living in their cars, sometimes they’re living on somebody’s couch for a little bit, and oftentimes, they don’t know about the services,” Sanchez said. “Every student has a story and we want to make sure that they feel okay. There’s no black and white. [Rather,] we’re going to bend as long as it takes for us to meet you where you’re at.”

Over time, Sanchez said she’s seen a priority of more sensitive approaches specialized to each situation of chronic absenteeism over broad, correctional procedures that expand beyond just PUSD.

“There’s definitely a shift countywide,” Sanchez said. “Through the County Office of Education, I’ve personally been witness to the shift to addressing social and emotional needs first. I think we’ve all learned from pre-, during, and post-COVID that if a student is not ready to learn because they’re impacted either with housing, or with a specific need cognitively, they won’t be [able to] focus on their academics. The county has been very supportive of that, and I appreciate that shift because it’s more solution-oriented to each individual student.”