Alex Kun (9) doesn’t know exactly when he stopped reading books. With childlike excitement, he used to derive wondrous enjoyment from skimming his hands over the spine of a book, flipping its pages, and immersing himself in its printed words. He could think of nothing more fulfilling than the notion of continuing to the next chapter or picking up another novel, ready to engage himself in an entirely new world with endless possibilities.

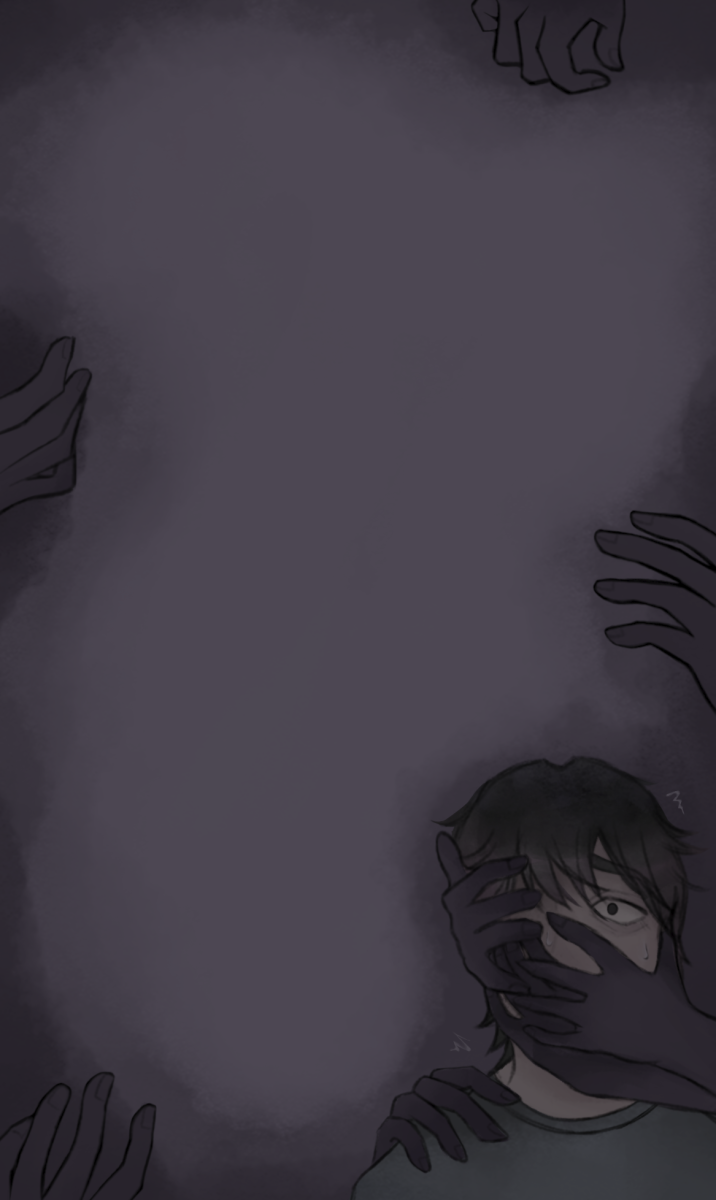

But, those days of fervor now feel foreign. At the present, Kun said the sight of a book seems simply uncompelling, nothing more than needless ink bound on paper.

“I just don’t feel drawn to books anymore,” Kun said. “I used to read upwards of three hours a day, and I’d read several books in the span of one sitting. It used to feel so entertaining. In the past, I [struggled] to find more to read, going to the bookstore every week to find something new. But now, it’s a completely different problem. I have 20 books on a list I want to read, but the moment I pick [a book] up and get like five pages in, I’m immediately bored.”

Kun attributes this apathy to his lack of motivation to read as well as how easily distracted he is. Dr. Polly Chen, an assistant professor at the University of Nottingham in Malaysia, trained in Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology, said that this century has seen decreasing attention spans. In fact, in a study performed at her university, they found that a large majority of young students performed poorly focusing on a singular activity.

“In a very recent cognitive test, we measured how good [college] students are able to inhibit irrelevant information while attending to an assigned task on a computer,” Chen said. “We used eye tracking to follow people’s eye movements to see if they were paying attention while sudden stimuli appeared. They were supposed to voluntarily look away from that distracting stimuli, but interestingly, we found that students are actually not good at filtering out irrelevant information. The students found it quite difficult.”

One possible explanation of this, Chen said, was due how students are becoming accustomed to shorter duration media. Kun agrees with this, crediting his abrupt transition in reading habits from when he was first introduced to the world of social media.

“When I first started using Instagram and other [apps] in the seventh grade, it was [overwhelming],” Kun said. “Watching reels, scrolling on TikTok, and being on YouTube feel so much more attractive and enjoyable now.”

Dr. Karen Lafferty is a professor in the School of Teacher Education at San Diego State University and National Board Certified English/Language Arts teacher. She teaches adolescent psychology in order to further engagement from students in the classroom and said that social media is purposefully curated to be extremely appealing to teenagers.

“Social media and our phones in particular are engineered by people who studied psychology,” Lafferty said. “The creators of all these apps know that the adolescent brain is uniquely wired to respond to social feedback, and they stimulate that by using the algorithms that are designed to give you a little hit of dopamine each time you interact with them or get a notification. Essentially, social media is designed to be addictive. So, in the competition for attention, reading doesn’t compete very well.”

Therefore, instead of reaching for a book and engaging himself for a long period of time, Kun reaches for his cell phone for short-term entertainment.

“It’s also less time-consuming and more interesting when it’s in that format,” Kun said. “The content of a book may be interesting too, but I don’t feel that into it. It’s literally just words on paper. Why would you want to do that when you have action-filled, rapid, comedic [media]?”

Sora Page (11) said she feels the same way. During the hectic transition between middle and high school, she found herself pushing aside the books she used to unwind with.

“I literally [used to] read every day,” Page said. “I would always have a book in my bag and when I’d go home, I’d read a book to relax. It’s how I went to sleep most days. But now, I’m just so busy. I go to school, do extracurriculars, go to practice, go home, and do homework for hours. After spending 90% of my time doing these tedious, tiring tasks, at the end of the day, I just want something quick and mind-numbing. So, instead of reading, turning to social media for a boost of dopamine and just rotting in bed on my phone feels better.”

Page said reading takes immense concentration and attention, while her phone allows her to mindlessly scroll. Since books no longer serve the purpose of entertainment for her, she said they feel useless.

“Reading forces you to sit down and take your time,” Page said. “I don’t want to go through the effort of reading after a long day, so unless it’s for a class, I just don’t find reading to be a priority anymore, and I don’t make time for it. I feel like I could be doing other things, and it doesn’t feel productive. I know reading is helpful in general, but those positives are easily ignored with everything else going on in life.”

The allure of easy entertainment is obvious, but Lafferty said overlooking the value of reading can be detrimental to the development of necessary critical thinking skills.

“Reading is a uniquely human capacity,” she said. “You are doing really high-powered mental work to recognize different symbols and connect them in the context of words and sentences, and that requires–and builds–deep knowledge and understanding. In doing so, reading builds stamina and your ability to focus for long periods of time as well, while social media does the opposite. So, by choosing not to read and go on social media instead, you are trading off long-term benefits for short-term enjoyment.”

Kun and Page have witnessed firsthand the drastic effects of their exchange for fast-paced pleasure when it comes to focusing and providing insightful discussion. Kun said the majority of his classmates and peers are having similar experiences.

“I feel like, not only mine, but everyone’s attention span is shrinking so much,” Kun said. “I can barely sit through an hour of lecture and I can’t actively listen the entire time. I see kids playing video games on their phones during class and zoning out a lot. I’ve also seen changes in how difficult analyzing texts is for me because when you read more, you are just exposed to so many more writing styles, ideas, and other symbols — you pick up on those patterns and better understand how authors use them when they write their books. When you stop reading, it’s much harder to pick up those same patterns.”

Lafferty said that without the foundation of literary knowledge, it’s difficult to achieve in-depth analysis and develop the ability to connect complex ideas to previously learned ones.

“One of the things that reading grants us is a wider perspective of the world,” Lafferty said. “If you think about psychology, you are essentially schema-building through reading and constructing an understanding of the content. [Schema-building] describes the process of how you sort information into categories of topics you’ve already learned and connect them together. Not being able to deeply read deprives you of the diversity needed for true comprehension.”

Page said when she finds herself challenged by trying to analyze a text, it’s much too easy to resort to technology.

“I’d be lying if I said I’m always able to understand what [I’m reading],” Page said. “Sometimes, even if I go over a text multiple times, I still don’t know what’s going on. Defaulting to searching up analysis from sites like SparkNotes happens way more frequently than I’d like to admit, and I find myself thinking about things less because of how easy it is to find analysis about a book. Of course, from then on, I try to formulate my own opinions, but I tend to rely on [the Internet] to point out things I don’t notice.”

Lafferty said she has too often witnessed this phenomenon in her own students throughout her years of teaching and how relying on the Internet prohibits the process of individual, original thinking.

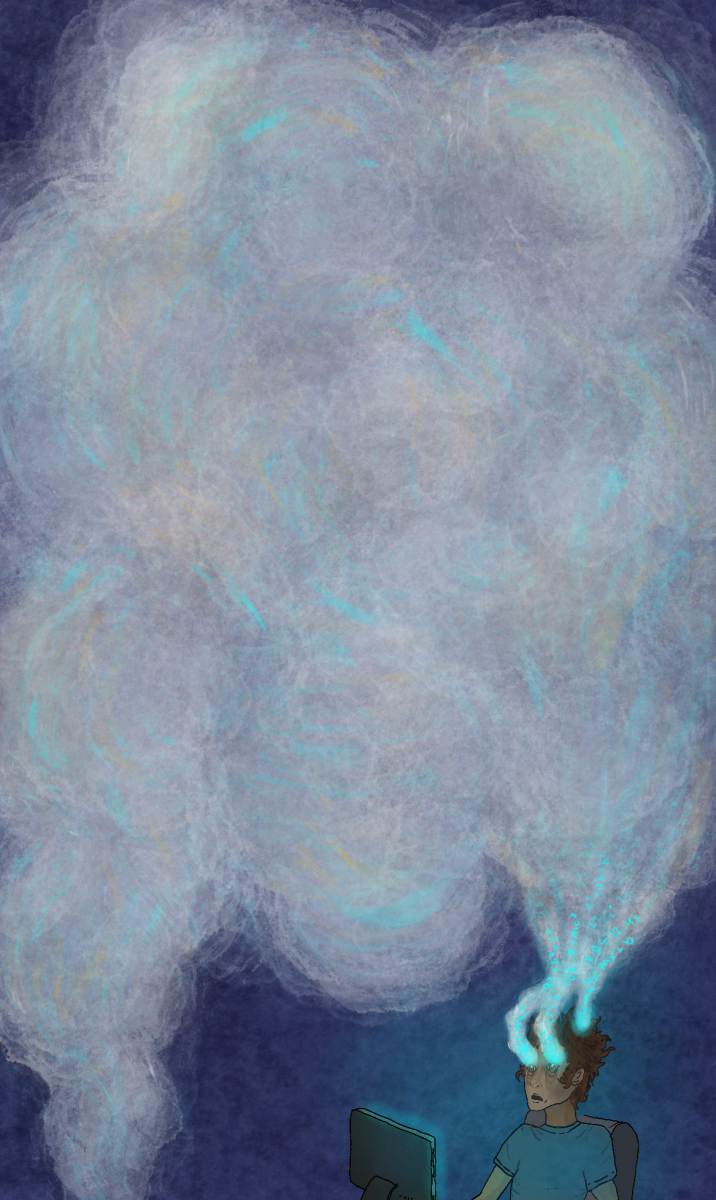

“What you’re giving up is your independence,” Lafferty said. “If you’re saying, ‘This is too hard for me to figure out, I’m just going to go look up the answer,’ you aren’t growing your brain and your ability to be a good reader. You’ve also become dependent on someone else doing your thinking for you, which is especially harmful because a lot of what’s happening with the teenage brain is laying down neural pathways that will carry people into adulthood. And, so, if you aren’t doing difficult things or challenging yourself to think, those pathways aren’t being established.”

Claire Choi (11) didn’t grow up reading much. Facing similar problems to Kun and Page, she finds herself tremendously reliant on technology, rather than her own mind.

“When I was younger, I didn’t have much of an interest in reading and thought it was boring,” Choi said. “I think that had an effect on how much longer it took me to read and process everything [as well as] be engaged in the material. I think we, as a generation, are so used to doing all our work online and getting all our information from [technology]. ”

This dependency has a possibility of turning into a dangerous reality if we continue to rely on technology to provide answers for us, Lafferty said. If the general population keeps surrendering control over their own thinking, power will be concentrated in those who are able to process information for themselves or are arranging the algorithms on which we so rely.

“When you’re reading, you’re the one in control,” Lafferty said. “You are making the choices on what information you are consuming, instead of having an algorithm serving it up to you. Then, when we are talking about democracy and you end up not being able to read and sift through the information on your own, you will become really dependent on someone else or technology to do that for you, which affects your ability to vote for yourself. So, if the majority of people don’t have that ability to deeply process things, we better hope that people who can have good intentions.”

Kun shares this grim outlook on the future but said he feels helpless to stop it.

“[I’m fully aware] that my choice to be on my phone rather than read is harmful,” Kun said. “Everyone I know is making the same choice and it’s going to have negative effects. I just haven’t been able to make myself do it.”

Lafferty suggests that those who want to read more should start off small in order to slowly combat the effects of technology on our ability to focus continuously.

“I would say just start for 10 minutes a day,” Lafferty said. “Set a timer for 10 minutes and move your phone to another room. What’s realistic for students is to build up the stamina and focus to read little by little, and eventually, 10 minutes will feel short and you’ll keep adding more time. This will make you a better reader and you’ll begin to rebuild the neural pathways in your brain.”

Despite her previous unwillingness and reservations, Choi has promised herself that she will make an effort to read more.

“It’s been really hard for me to start,” Choi said. “I had to get rid of the idea that reading a book was ‘work’ and too much effort. Changing my viewpoint on reading and shifting it to see it as educating myself and learning more about the things I enjoy turned it into a hobby. I began to see a new side of books that would [appeal] to my curiosities and used them to inform myself on topics like psychology, current events, and literature. I go to Barnes and Noble and [get] books maybe twice a week.”

Though it’s still tempting for her to entertain herself through social media, Choi said that when she does read, she feels all the better for it.

“It does take motivation, desire, and discipline to actively stay engaged in reading,” she said. “Sometimes I’d just rather watch Netflix or go on Instagram. But, I’ve found that reading gives me so much more fulfillment. Rather than being on your phone, it’s more satisfying to finish a book.”