Reflecting on their journeys: families help students embrace their cultures

Ethnic studies courses present the opportunity for students to challenge their worldview, empathize with those different from them.

When Armita Fazel (11) was in sixth grade, a boy asked her a seemingly innocent question, “Are you Iranian?” As she responded yes, the boy proclaimed that all Iranians were terrorists, then asked if she was one herself. After that day, Fazel began to view Iran as radically different from the place that she visited each year with her family. The image she had formed of her parents’ home country became a muddled collage of America’s perception of Iran and her own.

Before this, on her annual trips to Iran, she described herself as being able to explore a bubble that lacked exposure to the outside world and preserved the rich culture and traditions of the Iranian people within. Each year she traveled to a different state of Iran with her family and visited the landmarks of each one.

“The people there are very polite—not just to people they know but they’re very welcoming to everybody,” Fazel said. “If you meet a stranger in the street, they’re willing to do anything [for you].”

In America, her parents hoped to keep her connected to her roots, so she attended Persian school, where at first she learned to read, write, and speak in Farsi. Then, as she grew older she was introduced to a more interactive, engaging curriculum in which she learned about Persia’s many dynasties, as well as how to cook traditional meals with her family.

Despite having this first-hand perception of her country, she still believed the many misconceptions surrounding Iran. American media detailed only the atrocities and faults of Iran, often excluding America’s hand in them, she said. As the media and people surrounding her villainized her country, she began to feel as if it were her against Iran.

“I started looking at and hating my country, and realized that people are right, [that what Iran is doing is] not good,” Fazel said. “People tend to view Iran as what they see in the media, but that is all the government. It’s hard to separate the government from the people.”

She began questioning why her family in Iran did not stand up to a government that suppressed them. When she visited, she began arguing with close relatives about the lack of freedoms she had there as a woman. At this time, her faith in Iran wavered.

“When I go there, as a female, I need to wear long sleeves and long pants, cover my hair, and I’m not allowed to go to any sports games because it’s seen as a ‘male thing,’” Fazel said. “I would constantly argue with them, and they had to help me see that that’s how their culture is, and it’s not their choice.”

Seeing the Bigger Picture

The more she stepped back and viewed the country holistically, she realized the country hadn’t drastically changed from being the second home that was once so familiar to her, but instead her own views had been reshaped by a Eurocentric narrative that left her country’s viewpoint out of the picture. She had to make a conscious effort to challenge her own biases by conducting her own research. Attending Persian school, which was once a burden on her and her brother, became something to look forward to that connected her to her culture.

“As a kid, I would hate [my culture],” said Fazel. “I would say I don’t want to be anything like [my parents]. Growing up, especially with Persian school, my brother and I would cry and scream whenever we had to go because it was such a hassle, but now, I’m a TA and the kids that I work with do the same. I tell them you’re going to like it when you’re older. When I’m older, I’m going to be teaching [farsi] to my kids and I’m going to be visiting Iran every few years so they have that influence from their culture. ”

Despite reaffirming her pride in her country, she still, at times, hides the fact she is Iranian from others.

When President Donald Trump authorized a U.S. drone strike that killed Iranian General Qassem Soleimani on Jan. 3 of this year, some people believed this would be the start of World War III. Many Americans laughed at this threat—they posted memes and videos poking fun at what a war with Iran would look like. Meanwhile, Fazel and her Persian friends feared that going to school would result in verbal attacks from their peers and ridicule about their country.

Fazel and her friends’ feared their peers lacked empathy and understanding at this time. Fazel said she believes the racial intolerance prevalent in schools today can only be solved by a curriculum that considers and teaches all racial perspectives. Her trips to Iran gave her a perspective of her country that was far different from the one she encountered in America, but most students don’t get the opportunity to immerse themselves in their own or others’ cultures. She said, because of this, it’s even more imperative that history and other social science courses reflect an objective viewpoint in which students can decide who the heroes and the villains of the stories they’re being told are.

The field of ethnic studies was designed for this; it gave a voice to those in America who were silenced and gave them the opportunity to tell their side of history, said Professor May Fu, an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of San Diego. The field was born in 1968 when multiracial student groups from San Francisco State University led a five-month strike on their campus, she said.

“Black, Asian American, Latinx, American Indian, and white students could no longer accept a Eurocentric education that failed to address the salience of race and racism in U.S. society,” Fu said. “These student activists insisted on a ‘relevant education’ that analyzed how race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and other social categories structure society and determine life chances and opportunities.”

Intertwining Narratives

During the 1960s, as the fight for ethnic studies was gaining traction, the civil rights movement was at its peak. Amaya Bryant’s (9) grandfather often detailed the hardships of segregation during the civil rights movement to her—an account of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death and its rippling effects on America. Learning about Black history helped her accept and foster pride in her race and ethnicity. While she took pride in her identity, she had to develop thick skin to guard against the racism and intolerance of others.

“When I was in sixth grade, and it was around the beginning of the school year, some little school boys started calling me the n-word,” Bryant said. “I think they genuinely didn’t understand how bad it was to say because they thought that they were just messing around. Some people just don’t understand the gravity of what they’re saying, and it really affects other people.”

Although topics such as slavery and segregation are often covered in school curriculums, Bryant said it only scratches the surface of the complexities of the institutions themselves. Bryant’s great great grandmother was a slave, and one of her ancestors was a soldier in the Civil War. Having already been taught about the Civil War and slavery in school, she was able to intertwine the narratives of her relatives with what she was taught in school to create a multidimensional understanding of Black American history.

With the prevalence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Bryant said she feels the events of today are making history, and this must be reflected in the history books taught to students.

“The ongoing Black Lives Matter movement is the most significant global grassroots movement in over 50 years,” Fu said. “It spotlights the ongoing legacy of anti-Blackness, the failure of institutions to protect and empower aggrieved communities, and calls us to participatory democratic action. Ethnic studies curricula answers that call for all communities to come together, listen to the voices of those who are most impacted, and dismantle systems of white supremacy and discrimination that continue to harm our communities.”

Amplifying the Voices of the Silenced

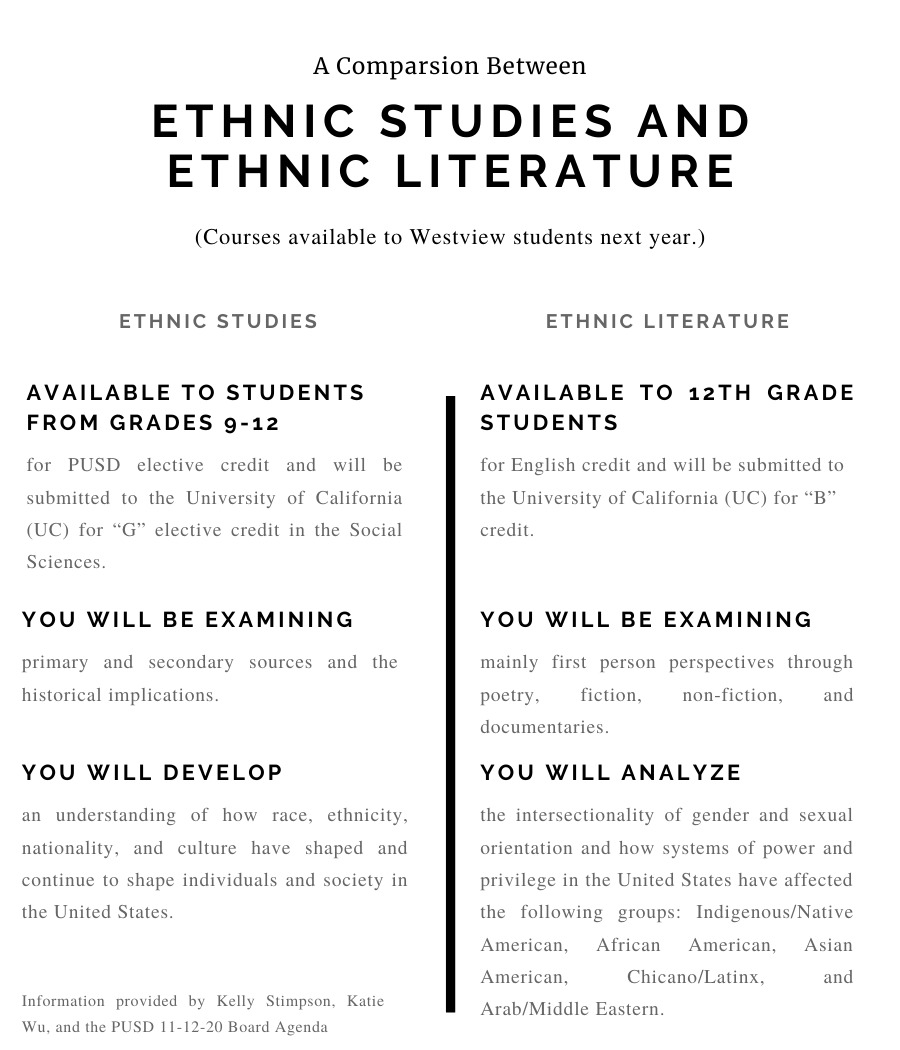

The voices at Westview are not going unheard by Westview English teacher Katie Wu, who is working on creating a senior-level English ethnic studies course for students at Westview. The course has already received district approval and will be offered the next school year.

“Ethnic Literature is a senior-level course that promotes cultural understanding and empathy through a deep analysis and examination of how systems of power and privilege in the United States have affected the following groups: Indigenous/Native American, African American, Asian American, Chicano/Latinx, and Arab/Middle Eastern,” Wu said. “In addition, the course will examine how power and privilege is a complex framework that affects one’s race, class, gender, and sexual orientation.”

The Ethnic Literature course was introduced by Wu this year in response to the hundreds of posts uploaded by Instagram account @BlackInPUSD detailing accounts of racism within the district.

“Reading the @BlackInPUSD posts and seeing the racial inequities erupt over the summer really lit a fire within me,” Wu said. “It pushed me to be more introspective by examining my own educational experiences in mainly white schools as a first-generation immigrant.”

Social science and English teacher Kelly Stimpson has also been developing a social science elective course called Ethnic Studies that she hopes will capture the role that communities of color have had on American history and culture.

“This course is designed to develop an understanding of how race, ethnicity, nationality, and culture have shaped and continue to shape individuals and society in the United States,” Stimpson said. “One of the purposes of the courses is to learn about the perspectives of various cultures in our community while allowing students from all backgrounds to better understand and appreciate how race, culture, ethnicity, and identity contribute to their experiences.”

According to data compiled by the Voice of San Diego, Poway Unified School District (PUSD) is ranked 43rd of 45 districts in San Diego county in terms of the ratio of teacher-to-student diversity. With PUSD’s newly approved Racial Equity and Inclusion plan, 12 new black teachers and one black assistant principal have been hired in the district.

Wu said she hopes her class finally empowers students of color to believe they have a place in history and the classroom. To ensure students have a say in the process of creating the course she encourages those who are interested in helping her develop this course to reach out to her.

Fu emphasized the important role a diverse education can have in a student’s life.

“Schools are hubs of knowledge, and knowledge is power,” Fu said. “Ethnic studies utilizes a transformative pedagogy that empowers all students with the information they need to know their history so they can know themselves.”

As Bryant and Fazel are at a time in their lives in which they are learning to accept and take pride in their culture and ethnicity, it’s important they are taught ethnic studies to learn to contextualize their identities and backgrounds, they said. With these new courses proposed by Wu and Stimpson, there’s hope that all students at Westview will have the opportunity to understand their role, whether that be as a person of color in America or as an ally, that supports these marginalized groups.

“I may not have a great mass of power, but I have the power to write a course that would hopefully engender social justice at our school site and in our greater district,” said Wu. “It really becomes imperative for leaders to be willing to go against the dominant culture. Ally is a verb; it is not just a hashtag.”