Picking up the Pieces: Processing Grief

Caught between remembrance and moving on, students navigate the grief of losing a loved one

In Amy Nguyen’s (12) previous home in Linda Vista, carefully arranged incense, fake gold coins and a framed photo of her grandfather stood in the living room. The incense was to be lit on Lunar New Year, the anniversary of her grandfather’s death, and any time they gave her grandfather offerings of food throughout the year. The coins were to extend wealth into heaven. The photo was to remember him by, and all were to remain on display every day of the year.

Together, the objects made up the shrine her family erected for her grandfather after he passed away when Nguyen was in third grade.

Nguyen grew up with her grandfather constantly present. He was the one who took care of Nguyen and her younger sister when their father went to work and their mother was busy around the house.

“He constantly showed me affection and attention, and he supported my dreams when I was younger,” Nguyen said. “I used to want to be a doctor, and he would help me organize his medications and feed him his medication [as a way to encourage me].”

Nguyen looks back on her memories with her grandfather fondly, but for a long time, she had trouble coming to terms with the death as a child.

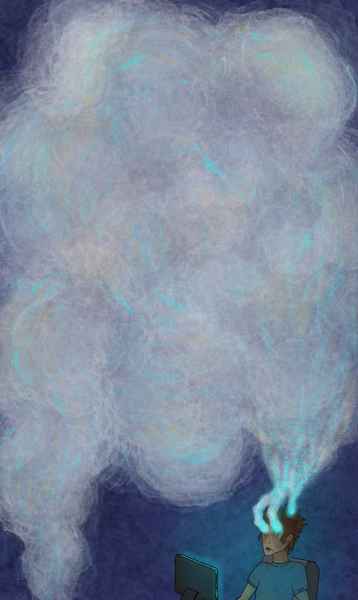

“I grew up with him my entire life, and then I was expected to continue without him, and I couldn’t process that thought [as a child],” Nguyen said.

Holding on to What’s Left

The shrine her family had set up in her previous home in Linda Vista was one way Nguyen said she felt she could remain connected to her grandfather, but when her family moved, the shrine was left disassembled in a cardboard box in a corner of Nguyen’s living room, only to be taken out for the Lunar New Year.

The incense, which is supposed to be lit to remember one sole family member who has passed on, is now instead used to remember her grandfather on her dad’s side, her grandmother on her dad’s side, and her grandfather on her mom’s side all at once. Before the move, her family would give offerings to Nguyen’s grandfather at the foot of his shrine regardless of whether the day was a special occasion, as a way to acknowledge the memories and presence of her grandfather. This included offering her grandfather food, such as fresh fruit, before eating it themselves.

Her family used to give offerings year-round, but now only do so on holidays like Lunar New Year, taking out the shrine from its box in the living room only to return it there when the day is over.

Nguyen said she sometimes feels that with the loss of these offerings, her grandfather, too, is being forgotten.

“We used to constantly give [our lost family members] offerings,” Nguyen said. “Every time we got a large meal, we would present it to them and give them the offering of the great meal before we ate. We used to celebrate [my grandfather’s] memory on his death day as well as his birthday, and when we moved, all that was kind of left behind.”

These outward acts of remembering her grandfather are one example of how someone can mourn a loved one. But mourning a loved one and grieving for them isn’t one and the same, said Certified Clinical Trauma Professional Christine McWilliams. McWilliams holds a Masters of Science in Professional Counseling from Grand Canyon University and specializes in grief counseling.

“Mourning is the open expression of sorrow and other feelings and is often associated with an event such as a wake or funeral or spreading of ashes as you intentionally make the time to honor the loss,” McWilliams said. “Grieving is a lengthier process that happens over time as you process the internal thoughts, feelings and meaning of the loss as you move forward into the next phases of your life without the loved one.”

Nguyen said she feels that acts of mourning have been a powerful tool to help her navigate her grief, but since her family’s move to Rancho Penasquitos, she has largely had to mourn on her own.

“I felt like I was the only one who remembered [the days we would mourn him] and what we used to do,” Nguyen said. “I feel like leaving somebody’s memory in the past and not continuing to remember them is more of an injustice [to them] than moving on, but still accepting what happened.”

Prior to his passing, her grandfather’s health had slowly been declining due to a combination of health issues. Nguyen remembers that her parents became increasingly concerned as he would do things that didn’t seem right to them, such as going for walks when it was pouring outside, or forgetting to turn the lights on when going to the bathroom.

When Nguyen was in first grade, he was hospitalized for months, and when he came home, he was situated in a hospice bed, where he was attached to an IV and given a strict diet with food provided by the hospital. One day, Nguyen found her grandfather hunched over the railings of his hospice bed, not moving, not breathing. Her parents had to call 911, but he was able to be resuscitated and then stay in the hospital for the next few months.

As the weeks went on, Nguyen’s parents visited the hospital less and less until only her father visited. Then, eventually, he stopped visiting too.

“[My sister and I] didn’t actually get told what happened,” Nguyen said. “We asked [our father], ‘Why aren’t you at the hospital, why aren’t you with Grandpa?’ I think because [our parents] didn’t tell us right away, our questions bore them down to the point where they had to give us news about what really happened.”

Even in the days leading up to her grandfather’s death, Nguyen said she felt that her family was trying to move away from the topic, as death was already a taboo subject in their home. To a young child who hadn’t had any experiences with death before, the silence surrounding her grandfather was confusing, Nguyen said.

“Nobody really explains how death happens,” Nguyen said. “And for my grandfather, I couldn’t comprehend that he was gone from my life.”

As Worlds, Memories Shatter

Though she wasn’t given many answers, Nguyen was given time as her grandfather’s health deteriorated over months.

Esteban Marin (11), however, had much less warning.

Though Marin’s mother was often in and out of the hospital for most of his life, the hospital visits had become routine by the time he was 8, and Marin didn’t remember his mother feeling particularly in pain the night before she passed away.

The summer before sixth grade, Marin was encouraged by his mother to attend a paintball camp. He didn’t want to go initially, but she was convinced he would have fun, and he did.

When camp ended, he wanted to tell her she was right. However, when camp ended, she wasn’t waiting outside to pick him up. His father and older sister were waiting instead.

“The way my dad told me what was happening was like, ‘She’s in the hospital, but things are looking really good, she’s good, but she might die,’” Marin said. “And the night before, she was literally in perfect health. It felt like a joke. Like a mean joke. I was kind of just in denial, like, ‘It’s not happening—they’re gonna find a way to save her. It’ll be fine.’”

McWilliams said that although the linear pathway of the popular theory of seven stages of grief (shock, denial, anger, etc.) isn’t a completely accurate model, those grieving may naturally experience denial as a first reaction to losing a loved one.

“Denial can be a first response someone may experience as for some it may help them manage the intensity of the emotions and loss,” McWilliams said.

However, Marin’s initial denial quickly subsided when he arrived at the hospital and his uncle, grandfather and cousins were all in the waiting room.

“I sort of knew as soon as my dad told me we were going to the hospital and things didn’t look good that she was going to die,” Marin said. “Like, something about the day screamed, ‘today’s the day,’ which was pretty depressing but at least it gave me time to brace myself for it.”

After around two hours of waiting at the hospital, Marin’s uncle drove him and his sister to their cousins’ home, where they watched Rad and waited for the news.

“We just waited for my dad to come to the house to tell us that she had died,” Marin said. “I remember that moment really clearly, because we were about three quarters of the way through the movie and we were just hugging in the backyard.”

Marin said that these connections with his extended family during and after his mother’s death are what kept him sane. Although the pain from his mother’s loss could be overwhelming at times, Marin said that occasional moments of healthy distraction from his family helped him to remember to live while carrying his grief.

“My cousins lived in the same neighborhood as me, so they had us over a lot because we didn’t want to be in our house,” he said. “Because it [helps to have] somebody to go over to and just like, watch movies, do whatever, go to the beach. And it was honestly that whole dynamic of people supporting us that helped me through a time like that.”

Having an external support system, Neimeyer said, can often lessen the pain one feels when they experience a loss.

“[Friends and family] can give us a welcome ‘time out’ from grief through simply taking in a movie, working out with us, or joining us for lunch, he said. “And they can often help us patiently sift through the experience of the loss, and make sense of the death and of our lives in its wake. However, without the special support that others can give, we can feel deeply alone in our grief, living in a silent story of loss that yearns for an audience beyond the echo of our own heart and mind.”

Nguyen said she didn’t feel she had a support system for her grandfather’s death, leaving her unequipped to understand her own feelings at the time.

“My parents were so overwhelmed and stressed about my grandfather’s health at the time and his passing after it that I didn’t want to add any more stress with my own feelings and problems,” Nguyen said. “I was more focused on not making my parents’ lives any harder than they were at the time, so I didn’t really get to fully process and understand what was going on at the time.”

Repairing the Image, Remembering the Lost

Though Nguyen had a difficult time processing the death of her grandfather as a child, she has since sought ways through which she can continue to process her grief today and honor her grandfather.

“[I would look] back on the memories I had of him and the memories we had together,” Nguyen said, “and I would keep in mind the things he liked and didn’t like and carry them in my life. I [often] eat his favorite meals and drink herbal tea when given the choice because it reminds me of all the times he had shared his tea with me when I was younger and introduced it into my life. By drinking the same tea it’s not only carrying on and reminding me of the memories I had of him but also carrying on habits that he would still have to this day if he was still alive.”

However, Nguyen acknowledged that she still isn’t fully done processing her grief. Indeed, grief doesn’t end a short while after a loved one’s death, McWilliams said.

“Grief changes over time,” she said. “It may not be as intense or life-stopping, but birthdays, anniversaries or special days can be a reminder of the person. A feeling of sadness and loss may arise for a moment as we miss our loved one.”

Marin said that he experiences unexpected moments of grief to this day.

“On Mother’s Day, I had nothing else to think about except for [my mom] and her memory and all the things she did for me and our family, and I’d cry because I couldn’t appreciate her in person,” Marin said. “I think a lot of people see grief is sort of like a bell curve, like you’re just up at the beginning and then you just sort of fall down and you eventually get over it, but it’s honestly not true. Because in the end, you did love the person who died. And no matter what, you’re going to miss that person.”

Marin has found that when grief inevitably flares up in his life, it helps him to process it by remembering the positive ideals his mother held—ideals which he strives to embody in his life.

“To me, the grieving process includes remembering the person and all that they did for you and others,” he said.

Marin remembers, for example, that his mother—a high school Spanish teacher—would sign each email sent to her students with “practice makes perfect.” He remembers that she would always open her classroom for lunch. He remembers that even in the midst of painful periods spent in the hospital, she would spend the hours playing games with him on websites like coolmathgames.com, making routine hospital visits a bit more fun.

“She always was that person who was motivating people to try their best and letting them know that their best is enough,” Marin said. “I think that teaching those lessons and keeping those lessons alive are really important to me because not only are they good lessons, but they mean something personal to me because they’re the lessons my mom taught me from a young age. But a lot of it is just not forgetting that they are still a person. They’re still a person in my life. They’re a figure I think about and talk about regularly.”

Dr. Robert A. Neimeyer, the director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition and a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Memphis, said that maintaining a healthy bond with someone you’ve lost can be an important way of processing grief long-term.

“[Someone who is grieving] can try new things, and perhaps things that are even a little weird, like writing letters of love or appreciation to the person we have lost in our journal or on their memorial Facebook page,” Neimeyer said. “We can even imagine their advice for us as we move forward with our lives, and it can be an interesting process to write that down too, in the form of a letter from them to us. Be creative and attempt to maintain a healthy bond with those we have loved.”

However, it’s important not to let the bond with our lost friends and family consume us, Neimeyer said.

“A healthy bond of any kind does not mean that we spend all our time or energy only with one person,” he said. “A healthy relationship—whether with the living or the dead, is a safe harbor to return to to feel cared for, and a launch pad to take off from to explore other worlds. Coming and going and then coming again, easily and without drama, is optimal in both cases.”

Processing Through Time

For Nguyen, maintaining a healthy bond with her grandfather has taken more intention on her part, she said. With the slow loss of her family’s traditional mourning practices, Nguyen has had to find ways to grieve and mourn on her own.

“When I was younger, when I first started out trying to honor my grandfather [on my own], it was hard because I didn’t really remember the day of my grandfather’s death and I couldn’t really ask my parents for the day, because that would be more of a tense, awkward situation that I didn’t want to put them through,” Nguyen said.

To remember her grandfather’s death day, Nguyen would look through her journals and calendars she wrote in daily as a child and count back the days to the death day. Putting in the effort to remember her grandfather, Nguyen said, is how she feels she can honor him and what he meant to her.

“I feel like everyone deserves to be remembered as much as they can [be], so I try to carry out habits to remember [my grandfather],” she said.

From lighting incense on someone’s death day, to reflecting on a lost figure’s values, grieving can take many forms. But whatever form it does take, it is entirely possible for it to evolve and shift over time, Neimeyer said.

“In a sense, grief does not end, but it can and usually does change,” he said. “So a heavy sense of despair and depression in the early weeks or months of grief may mellow into a sweet nostalgia or feeling of gratitude as months turn into years.”

Marin says that his grief has shifted from when he was a rising sixth-grader, coming home from paintball camp.

“My feelings about my mother’s death as I’ve gotten older evolved to where they’ve gotten more peaceful since then,” Marin said. “I’ve gone from being sad for myself for losing a mom to being happy she doesn’t have to suffer. I’ve accepted it a lot more, but it’s weird because it’s still something I’m processing, and that’s the thing: I don’t think you ever stop processing grief.”

However, that doesn’t mean that someone who loses a loved one will grieve all the time, Neimeyer said, nor should they feel obligated to dwell on their loved one. Yes, grief shows great care and love toward the person who has been lost, but grieving them does not have to be life-limiting, he said.

“Make a date with your grief as frequently as you need to, whether that takes the form of 30 minutes of reflection, journaling or listening to music that reminds you of your loved one,” Neimeyer said. “However, also give yourself permission to have fun, hang out with friends, engage in a creative project, or give time to your studies or work. Don’t simply flee into ‘keeping busy,’ but instead choose people and projects that have real meaning for you. This will help you grow through grief, rather than simply running from it.”

At the end of the day, a shrine is still packed up in a box in Nguyen’s living room. The incense remains unlit, and the photo tucked away. But Nguyen said she still takes the time to mourn her grandfather as much as she feels she needs to, welcoming her grief as a natural part of her life.

She remembers her grandfather. Marin remembers his mother. They carry these memories into their lives, but do not forget to live themselves.

“After the initial shock and grieving, I knew I had to keep going through life and not let the death take over my life, or else I wouldn’t enjoy anything,” Marin said. “I still remember [my mom] every day, but I’m in a place now where I’m okay without her existence, which I think is what she would have wanted for us.”