I’m standing in your corridor, I wonder what I’m waiting for, the leaves are drifting out to sea…

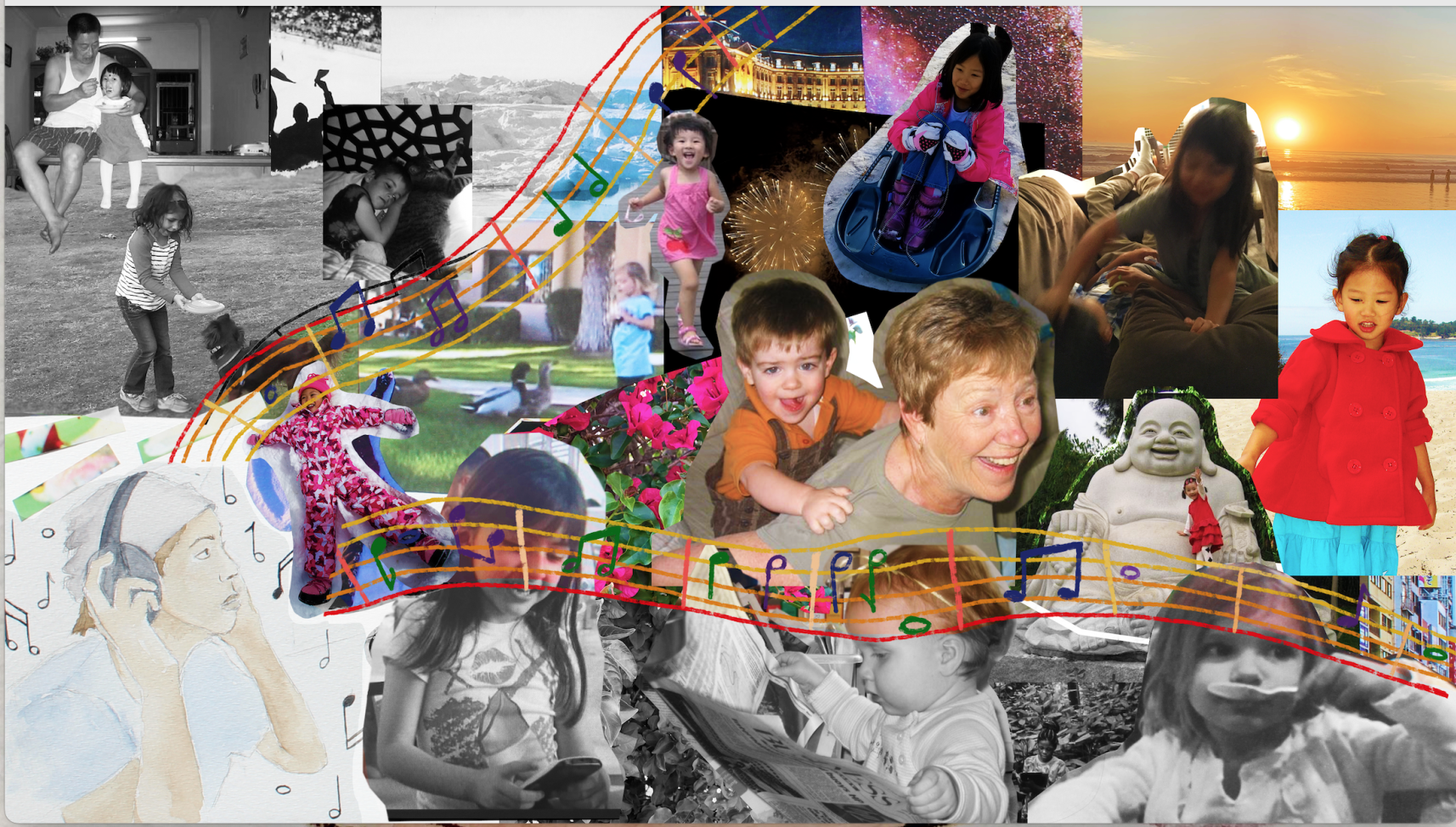

Every road trip started just like this: “I Want Everything” by Cracker thrumming through the car speakers. It started when Max Graham (12) was 3 years old, buckled in a car seat, his parents in the front as they coasted through Quesnel, British Columbia, great pines towering over them. Summer was brimming, its trees, its skies, its fleeting brilliance darting past each window. Graham shut his eyes, and when he did, he’d sometimes catch his dad unabashedly singing along, convinced that everyone in the car was sound asleep.

From this moment forward, in the back of his mind, Graham unknowingly began building his own musical time machine for the future.

“[My dad] would always play [the song] when I was younger anytime we were driving and it feels like a shot to the heart everytime I hear it because that’s not something I’d hear [anywhere else],” Graham said. “It’s painful in the nostalgic way because my dad and I used to be really close. It always just makes me think of how different things were.”

According to Dr. Ljubica Damjanovic, a researcher and experimental psychologist at Lund University, music is a powerful trigger for our memories and aids in shaping our sense of self.

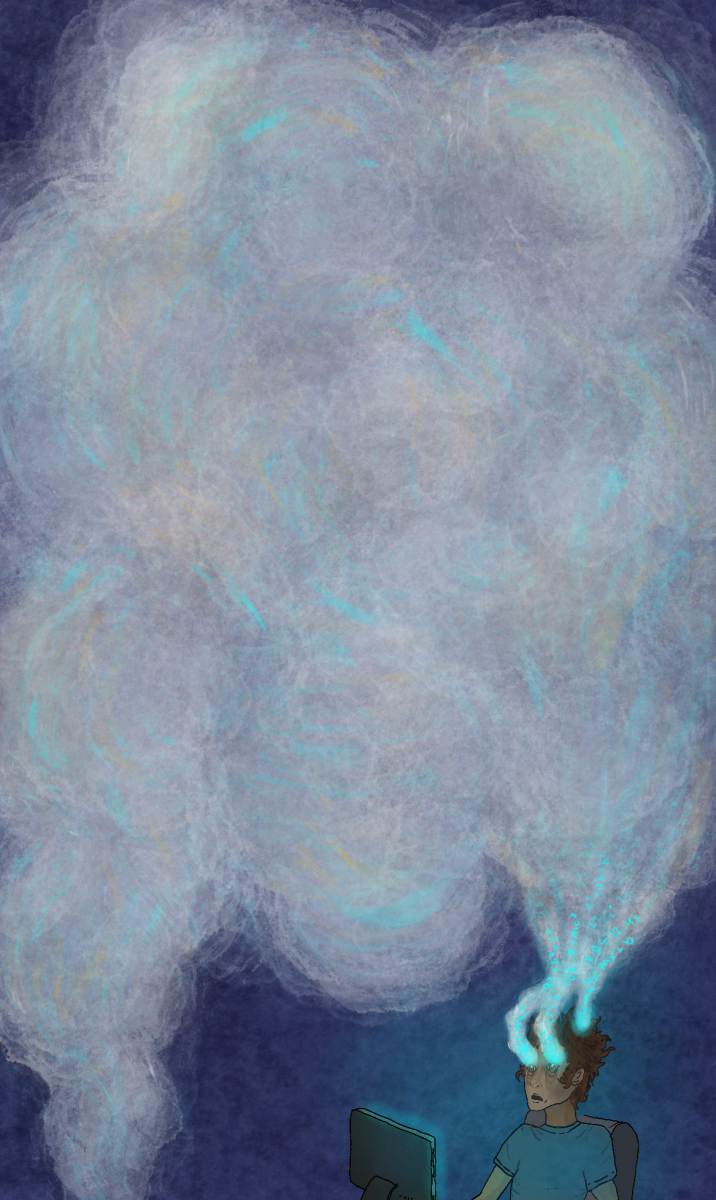

“[Music] can take us back to a specific time, bringing up feelings, people, and places linked to that moment,” she said. “It’s almost like music unlocks our memories instantly, making us relive those emotions. Neuroimaging studies have found that a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which is key for memory, lights up when we listen to music, linking it to past experiences. Our brains are constantly creating and reshaping memories, which is why music is often called the ‘soundtrack to your life’—it captures moments that define who you are.”

These defining moments marked by music for Graham helped navigate his emotions in retrospect. Lorde’s “Ribs,” for instance, known for its nostalgia-ridden sound, played this role in bridging Graham’s past and present self.

“I’m 17-and-a-half now,” Graham said. “[‘Ribs’] always makes me feel like when I was 13. I thought the world was ending and I was like, ‘I’m not going to make it until I’m that old’ and now I am that old. Sometimes I won’t realize that that’s what’s in my mind and then that [song will] evoke a reaction. I’m like, ‘Oh, so that actually was what I was harboring in there.’”

Among adolescents, Dr. Damjanovic said that research by professor Dr. Reed Larson at the University of Illinois concluded listening to music we enjoy during formative years of life encourages a sporadic, experimental exploration of identity.

“When we use music to manage emotions, random images might pop into our minds unexpectedly,” she said. “Sometimes, our brain goes into ‘movie-making’ mode, letting us create, change, or dismiss these images however we like. [Dr.] Larson, almost 30 years ago, suggested that music gives adolescents a way to imagine powerful emotional scenes, helping them form a temporary sense of self. It’s like a ‘fantasy ground’ where they can explore different identities while figuring out who they are.”

Growing up, Andre Oliver (12) was surrounded by music; his dad was a folk singer, he sang in bands, and played various instruments. Between listening to rock music in fourth grade, then R&B artists like Brent Faiyaz in middle school, Oliver was keen on expanding his musical knowledge. Even now, Oliver performs in bands with his friends and constantly indulges in music. Upon revisiting certain songs, Oliver said that feelings of nostalgia grounded him to his passion for performance.

“When I was younger, I was kind of a wild child,” Oliver said. “When I performed ‘Sweet Child of Mine’ on stage, I really just went all out. It was always with those really heavy and intense rock songs like ‘Highway Star’ by Deep Purple, ‘Welcome to the Jungle.’ I went all out, moving around, and looking back at it, I’m like, ‘What was I doing on stage?’ But in the moment, that’s what made me have fun and that’s what made me enjoy everything about performing.”

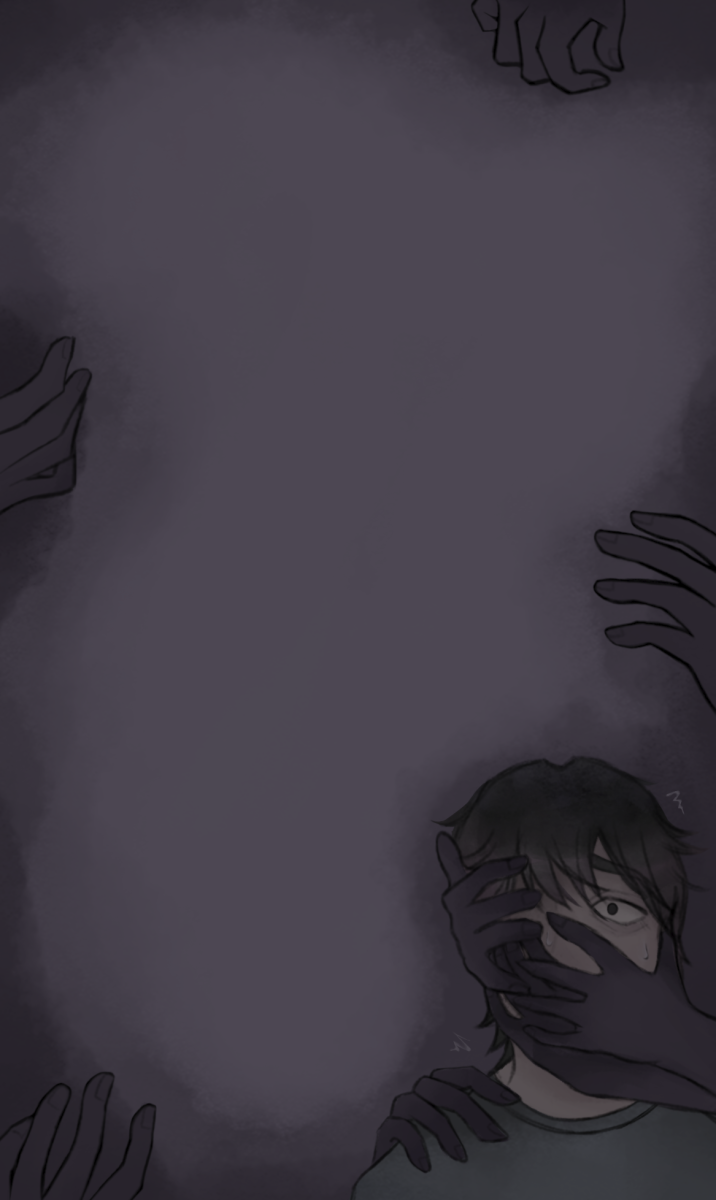

Eventually, soundtracking his life doubled as a defense mechanism. Exiting middle school, Oliver used music as a way to escape. Oliver was not a very socially interactive person and entering high school, he struggled to find connection. But consistently, music remained a friend he could always interact with.

“I didn’t know anybody, I was all by myself,” Oliver said. “The only way I could escape from this feeling of loneliness and not feeling too sad about it was just listening to music, mainly R&B and hip-hop, walking around the quad. How you interpret music and how you treat it, you [can] use it as a coping mechanism, as something that brings you away from reality. You kind of want to live in that sound, you want to live in that field of synthesizers and strings. You kind of forget yourself in the moment.”

Cognitive neuroscientist Sarah Hennessy, a 5th year Ph.D. candidate at USC’s Brain and Creativity Institute, said that music can be used as a coping mechanism, more often for adolescents, due to the greater need for emotional balance.

“There’s a bunch of research showing that adolescents in general are using music more to help emotionally regulate than like adults are,” Hennessy said. “There’s different types of ways that people use music to cope, especially in adolescence. Some people use music just to relax, to tone down their nervous system to put them in a slower, calmer mood while other people might use music to bring their energy up. Some people use music to sit more in the feeling that they’re already feeling. You can explore that emotion within the safe space of a song.”

Although Oliver used music as a tool to shake those times of isolation, Dr. Damjanovic said that much of the time, moments are more vivid in recall when the music associated contrasts from whatever emotion was being felt.

“In one of my studies, I found that when music’s emotional tone doesn’t match a visual scene, such as watching a brief clip of a wedding party set against a backdrop of slow-paced, sad music, people tend to form stronger memories than when there is a match,” Dr. Damjanovic said. “This was especially true with music people associate with sadness. Other studies show that music helps us manage emotions, creating a sense of balance. How we choose to balance our emotions depends on the situation and the personality of the listener.”

Being grounded back to a sense of self is a common thread in learning to balance emotions, according to Hennessy. Many studies have concluded that music preference formed in adolescence is also tied to forming a part of one’s core identity.

“Music that you listen to between the ages of 9 and 18 is probably going to be the type of music that you continue to prefer for the rest of your life,” she said. “We tend to solidify our preferences and one of the reasons for why is that adolescence is a big period of hormone change and developing your sense of identity. A lot of ways in which people do that in adolescence is by making choices where they can and music is a really easy way to do that. You end up developing your sense of self while listening to all this music and then that gets tied up in your preferences for music.”

Graham said that much of his music taste was owed to his dad; many of the artists Graham listens to now, such as Green Day, The Smashing Pumpkins, and The Cranberries, are artists of songs played for him when he was little. For Graham, music became a common ground for him and his dad.

“I got word of the Green Day and The Smashing Pumpkins concert and I [brought it up] to him,” Graham said. “He didn’t want to show it but he was so giddy. He was like, ‘I haven’t been to a stadium show since I saw the Rolling Stones in ‘96!’ When we went to the concert, it was probably the one night we’ve gotten along without beefing in a long time.”

Dr. Damjanovic said intergenerational connection is a special benefit of music, due to how universal the feelings they invoke are.

“It’s motivating to see how music connects communities and generations, showing that it truly is a universal language.” she said. “Nostalgia has a powerful social side. When people talk about nostalgic moments, they often mention sharing them with loved ones — family, friends, or partners. But it’s not just about relationships; big life events like anniversaries, births, or even the memories tied to your hometown can spark those warm, nostalgic feelings too. Music, in particular, has a unique ability to bring out these emotions, often making us long for the past. It’s no wonder that we turn to music as our personal time machine, helping us relive those rich, meaningful memories.”

Hennessy’s studies have largely focused on ways music can trigger memories for those who suffer from neurodegenerative diseases. In comparing older and younger adults, Hennessy found that our relationship with music stays relatively the same and can even grow stronger. Through autobiographical memory, a kind of episodic memory, Hennessy said we are able to view our lives as a narrative and story of its own, but even when it deteriorates, music memory remains due to how widely associated it is with different facets of our lives.

“We used functional magnetic resonance imaging [on] a group of young and older adults and we looked at how their brains were responding to music they knew were nostalgic or memorable for them,” Hennessy said. “They actually didn’t look very different, which is surprising and hopeful to me. Both younger and older adults showed activation of those memory regions that [connect] to our sense of self. How that looks in folks with neurodegenerative disease is a different question. There are a lot of anecdotes about folks with late stage Alzheimer’s and dementia still responding emotionally to music. One of the theories behind why that happens is because the networks that support music memory as opposed to autobiographical memory are more distributed in the brain. As you lose access to these memory regions, you still have access to the others and that’s the type of memory that’s a bit more resilient.”

According to Hennessy, music listening itself incorporates numerous parts of the brain. Processing music becomes more than just recognizing the notes, rhythms, or melodies being played

“The other aspect of listening to music is the contextual and personal connection to it,” Hennessy said. “If you listen to a piece of music that you’ve heard before, your auditory cortex is going to be active, but also parts of your brain that relate to who you are as a person and autobiographical memory are also going to be active. The whole brain is lit up when you’re listening to music. Music can activate parts of the visual cortex too, but we find that even when you’re listening to music with your eyes closed, both parts of the brain are active, which says something about what we visualize when we’re listening to songs that are important to us.”

When looking back on a certain moment, music reflexively pulls back layers of information, subtle reminders, and comparisons built up over time.

“If you think about these pivotal moments of your life, like maybe a high school graduation or a wedding, there’s always music involved,” Hennessy said. “You end up tying this emotional stimulus to the music. It unfolds over the course of several minutes, so your brain has a lot of time to take in all of that sound and connect it to whatever is happening around you. Music has this unfolding aspect.”

For Jude Sermona (10) music is a constant; his playlist is on shuffle while he’s walking through the halls, while he’s studying — music is even intertwined with his name, “Hey Jude,” by The Beatles, courtesy of his parents.

“I sometimes listen to music during math,” Sermona said. “It kind of gets me going. It makes me feel better and I’ve noticed that some of the tests where I listen to music, I’ve done better on than that I haven’t, which I think is because I also listen to music while studying. The memories that I have from studying are also embedded within the music I listen to. I think that it helps me get better grades on tests and that’s really interesting.”

Sermona often finds solace in music though emotional relatability.

“Music has helped me process emotions,” Sermona said. “One example is ‘Sympathy is a Knife’ [by Charli XCX]. It really encapsulates the feeling of jealousy. When I have been a jealous person, it really helped me process that and to get through it in a better way.”

Sermona said that above all else, finding familiarity in music, whether the reminders are positive or negative, is an invaluable method of self-comfort.

“Music is always present in my life,” Sermona said. “Usually, even when something’s really bad happening to me or I feel really terrible, I will alway listen to music. It’s just a comfort. It’s comforting to listen to music, listen to music that you’ve heard before. It’s comforting because it’s something you’re familiar with.”

However, Sermona has also found that his music tastes have transformed with how it affects him emotionally. In the past, Sermona’s main music artists of choice had slower, sadder discographies. Listening to this kind of music began taking a negative toll on Sermona.

“I have a sad playlist and I’ve noticed the more you listen to sad music the more sad you become,” Sermona said. “That’s why I don’t listen to Mitski anymore. I associate Mitski and other artists that have sad catalogs with sad memories and it brings down the mood, which is also part of the reason why I got so much into hyper-pop. [It’s] a very positive genre. Hyper pop is really fun because it’s really stimulating [and has] fun production. It has a bunch of positive feelings. Even some sad songs, they still have a positive vibe.”

Dr. Damjanovic said as much as music can heighten an emotion, it can also twist it. When viewing our own lives through an autobiographical standpoint, memories become similar to a movie reel.

“Both memory amplification and distortion can happen,” she said. “I’ve seen it in my own research. Filmmakers are masters at this—strategically choosing and placing music to heighten emotions and enhance specific moments in a movie. This creates a memorable, immersive experience for viewers, proving just how powerful music can be in shaping the way we remember and interpret scenes.”

Etched into precious moments in our childhood or nestled between passing conversations, music is ever-present in the ways we perceive and build our identities throughout our lives, Henessy said

“The coolest part of music to me is how we use it to form identity and community,” she said. “It’s pretty cool that we can make music together or listen to music together. It’s odd [how] these varying collections of sounds interest and excite our brains. We use music to connect with other people, we use music to connect to ourselves and those connections help sustain us through our whole lives.”