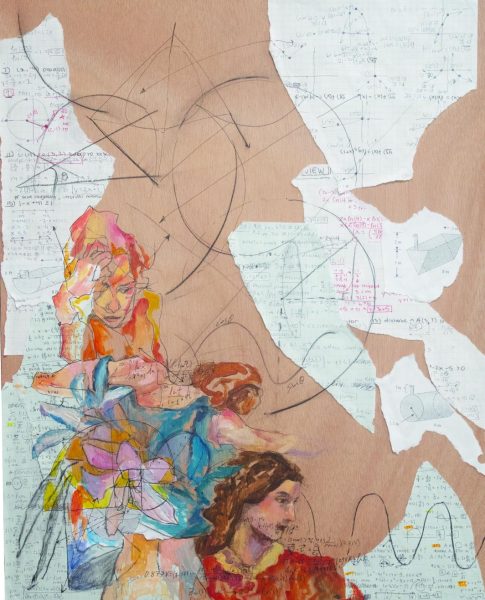

Rapidly and recklessly, the death of humanities in modern society is approaching.

Such studies have reached an all-time low according to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, dropping anywhere between 16 and 29 percent depending on the major. This is not a phenomenon limited to the U.S.. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development show that 24 of its 36 countries have seen significantly less interest in subjects such as literature, history, art, philosophy, and linguistics. By contrast, there has been an increase in enrollment for science, engineering, AI, and health-related fields due to a job market that seems to prioritize STEM.

Humanities is becoming less and less prevalent, and yet, in our rapidly developing world, a study of the humanities has never been more necessary; the loss of humanities threatens every single career and on a greater scale, the entirety of mankind. As Yale President Peter Salovey said in 2017, “We must value the humanities even in the midst of conflict and division. Only through the humanities can we prepare leaders of empathy, imagination, and understanding — responsive and responsible leaders who embrace complexity and diversity.”

James Vipatipat (’10), a business systems analyst for UCSD with a degree in structural engineering, said that being in touch with the type of thinking humanities encourages has been a key tool in his field.

“When you’re doing STEM, you’re more focused on the problem at hand,” Vipatipat said. “But, when you’re [participating in] the humanities, it shifts your perspective in a way that makes you think about people. There’s a more emotional aspect to it that’s really carried forward into my career today. The things I work on are logic-driven and even though I’ve pivoted careers [in the STEM field] multiple times in the past decade, I’ve noticed the ability to work with people, understand people, and think outside the scope of a project at hand has helped not only me, but others be successful. The humanities just opens up your view and broadens your opportunities.”

According to Vitpatipat, an example of this was in one of his previous jobs in the technology industry as a product manager.

“The key to [getting that job] was having good empathy,” he said. “It was a role that a lot of non-STEM people, like art or philosophy majors, would pivot into since it was more focused on the design and business aspect of whatever item the [company was] making. This is where the humanities really shined through because STEM majors lacked the empathy and understanding of their customers required to make a product marketable. [STEM people] understand problems and how they are building, but the humanities people are able to understand other people.”

Harvard philosophy professor Dr. Jeffrey Behrends agrees with this sentiment. Dr. Behrends said that studying philosophy or other humanities subjects is not only individually fulfilling, but also widely applicable.

“I think that studying philosophy is incredibly useful,” Dr. Behrends said. “For one thing, it’s personally enriching. When I was a teenager, I found it so empowering to use philosophy as a way of better understanding what ultimately mattered, what the world is fundamentally like, and what my place in it is. But it also sharpens a whole bunch of skills that are useful outside of philosophical contexts, like the ability to understand and evaluate complex arguments quickly and rigorously. In fact, the last few years have seen several business publications making the case that studying philosophy is especially useful to managers and executives.”

Daniel Tran (’23), a second-year pre-dental student at the University of the Pacific (UOP), who has been participating in Speech and Debate since his freshman year of high school, said that he’s seen how the philosophical and analytical thinking required in the events helped advance his academic endeavors.

“Especially when I did Public Forum [in high school], the cases we were creating had to last us three months or so,” Tran said. “We had to go through a lot of articles and a lot of different kinds of literature, like scientific, political, and even philosophical. We had to comb through all of this to look for information, evidence, statistics, different talking points, etc. When I got to university, because I am able to break down these kinds of complex augmentations on a finer level as compared to a lot of my peers, in my first year of research for a chemistry and microbiology lab, I am going to publish [a paper], even though I’ve barely had any experience with this kind of scientific writing. My advisor just told me that my writing and analytical skills were really solid; so, the skills I learned within Speech and Debate have really given me an advantage.”

Speaking on the practicality of humanities, Dr. Behrends referenced the Forbes article, The Business Of Thinking Big – Why Managers Should Study Philosophy, which details how billionaire hedge fund manager George Soros, billionaire investor Carl Icahn, CEO and Co-founder of Slack Stewart Butterfield, and many others, credit their philosophy degrees for being able to predict and pragmatically adjust to market and consumer behavior.

“I completely understand that many students need to approach college primarily as a means for getting a leg up in the labor market, and that more practically oriented fields look like the way to go,” Dr. Behrends said. “But the truth is that people who study philosophy find success in all kinds of pursuits, and I think that studying philosophy alongside something more ‘practical’ is a really fulfilling and useful route for a lot of students.”

YJ Si (’22), a third-year philosophy major and physics minor at USC, is doing exactly that. Si said he has heard about how humanities majors can be viewed as “useless” or “impractical,” but according to Si, his STEM and humanities focuses overlap much more than people might think.

“Thinking on a more technical basis is not something that’s just tied to STEM,” Si said. “There’s a similarity in analysis between STEM and humanities. We often see these things as very separated, but the truth is, the better you are at one thing, the better you get at another. The better you are at philosophy, the more you can see the implications of physics in our world. It’s the same thing vice versa too; I feel like contemporary philosophers don’t study how reality actually works, and physics is a way for me to understand the fundamentals in applying philosophical study to make sense of our world.”

Though the study of physics supplements his major, philosophy is Si’s first and foremost interest.

“As far as going into a job, that was never really my first priority with philosophy, which I’m sure tracks quite well with philosophy majors,” Si said. “When I got it to empiricism, especially with Hume, I realized that there are people who have dedicated their lives to shaping society with their conclusions. I want to be able to study what they’ve learned, so I can go beyond and be the next step.”

This idea of moving away from the status quo is something that Dr. Behrends said he believes the humanities can do.

“A big part of philosophy — at least as I understand things — involves understanding how rational argumentation works, so that we can first understand new arguments that we come across, come to some conclusion about whether they’re any good, and start doing some positive argumentation of our own,” Dr. Behrends said.

Tran also wants to create novel positive change and said that learning about current events in Speech and Debate helped him become more interested in keeping up with worldly issues as well as laws affecting the medical profession. According to Tran, it’s allowed him to immerse himself deeper into his career — not just simply hoping to become a dentist, but to question and change the field entirely.

“I went to the American Dental Educators Association conference in D.C., [March 8th-11th],” Tran said. “It was a free, pre-dental recruitment event, and they had 70 or so dental schools and admissions boards there. There were over 3,000 students that attended, and it was basically our chance to network. I found that the questions that I had asked those teams were vastly different than my peers. For example, I asked about how [the University of Pennsylvania Dental Medicine program] could prepare me to address legislation issues that come with health policy and health care. They didn’t expect those questions and they couldn’t give me a straight answer. So they had to take me to the back of their booth to consult the higher level people. Eventually, the [UPENN] head dean of admissions had to answer me.”

Humanities fields, Tran said, in general promote more curiosity and involvement in one’s surroundings.

“There is a different vibe when I talk with my humanities friends,” Tran said. “Obviously, I have a lot of fun with my STEM friends, but we really just focus on our pre-dental program and its coursework and studying. With [my humanities friends], there’s just more conversation about worldly issues. We’re talking about current events. Everyone in my [dental] program is just really busy with what they’re doing individually.”

Swasti Singhai (’23), a second-year chemistry major at UC Berkeley, said that being the Final Focus editor for The Nexus in high school allowed her to explore her interests in the community as well.

“The Nexus gave me freedom to pursue whatever ideas I wanted to talk and learn more about,” Singhai said. “It was really impactful for me because I could explore a lot of things I enjoyed independently and interview students, teachers, and experts to gain different perspectives. I don’t think that I would have had the motivation, for example, to go out and talk to someone who was pro book-banning [for one of my articles], without The Nexus. It was a way for me to express my creativity in a different way.”

Singhai is the city news editor for UC Berkeley’s newspaper, the Daily Cal, and is still able to write and edit a range of articles covering her school and community. Both Singhai and Tran said they have found a sense of belonging in their humanities activities, as opposed to the more competitive nature of their STEM majors. Tran, in particular, said that in high school, indulging in the arts was an irreplaceable part of his experience.

“In contrast to a lot of my other peers who dropped out of band going into high school, I wanted to try and continue because I just really loved music,” Tran said. “I first started off in a non-competitive band, but after a week, I immediately switched to competitive. Even though I knew I was going into STEM, and could have taken more AP sciences instead like all my friends were doing, I just needed that community and in the STEM field, I couldn’t find that. Music was my solace; there was more emphasis on collaboration, communication, and group accountability. I really didn’t know how valuable those memories were back then, but [music] shaped my identity.”

Overall, Singhai said that the dwindling of the humanities has put everybody in jeopardy.

“There’s just a lot of uncertainty in every field, including STEM,” Singhai said. “Without the ability to properly comprehend new inventions and information, anything new that might be discovered might not even matter because we can’t effectively communicate what it might mean. The impact that science currently has is going to be difficult to maintain with the current rhetoric and administration that neglects humanities. I’m not sure what the future entails, but I think something definitely has to fundamentally change for any field to have value now.”

According to Dr. Behrends, without assigning importance to humanities, we lose purpose and meaning in our democracy and in general, lives.

“It seems to me that the really pressing risk associated with declining enrollments in the humanities has to do with, first, a deadening of our ability to think about and align our actions with what ultimately matters, and, second, social losses in a shared understanding of how we are trying to live together and why,” Dr. Behrends said. “There’s a kind of originality of thought and critical thinking ability that one needs to really excel at any area of study, the sciences included. What’s distinctive of the humanities is our emphasis on nurturing reflection on what, ultimately, any of us think the purpose of our pursuits is, and how we can get along with one another in a world in which we’re going to disagree about that.”

Whatever the future holds, Si appreciates the impact of his philosophical pursuit.

“It would be disappointing if it turned out I would be a barista for the rest of my life, but the fact that I’ve learned to think about things in this very perceptive way is so incredibly valuable,” Si said. “At least, I’ll be an enlightened barista.”