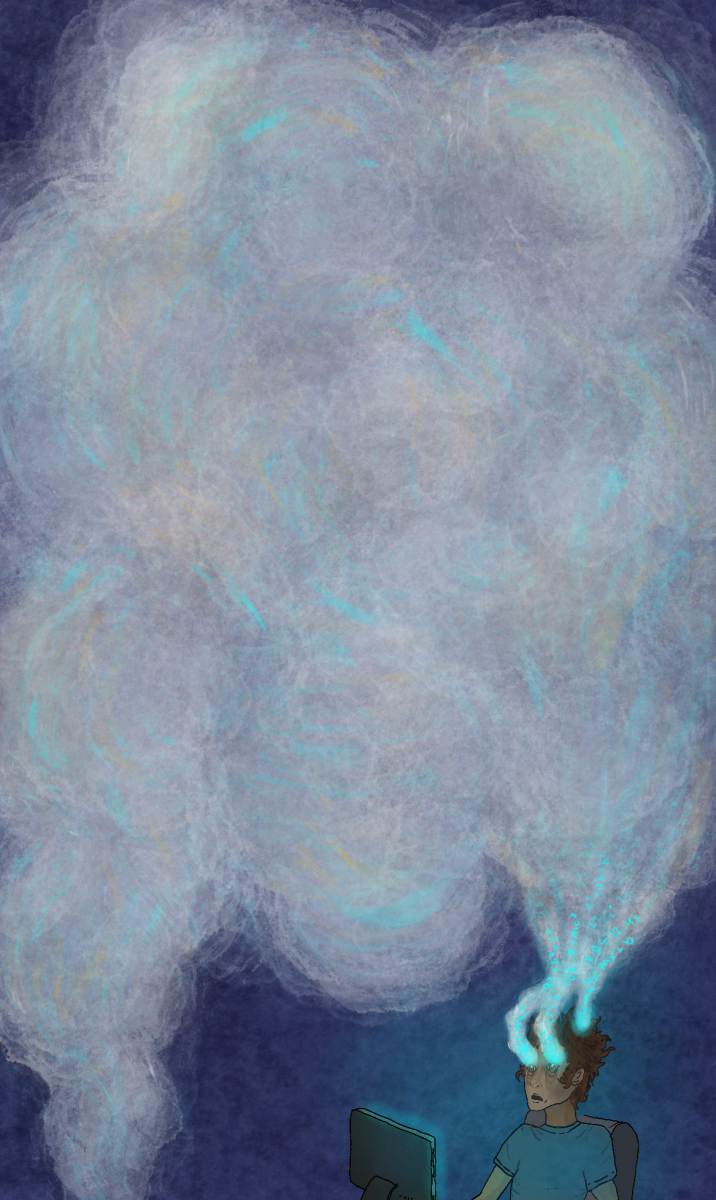

Eva Porter (12) scrolled through endless webpages as she scoured the internet searching for articles that she could use for her APES assignment. Glaring headlines of climate change news flashed across the screen as she explored, each prophesizing the impending collapse of aquatic ecosystems. In that moment, she felt trivial, devastated by the sheer magnitude of the issue and saddened by the inevitability of it all.

“I remember seeing so many different articles on how climate change was affecting coral reefs and killing all the coral in the ocean,” Porter said. “There were so many other bad things that were happening to the ocean at the same time. That was really sad to see as someone who loves the ocean and lives in California.”

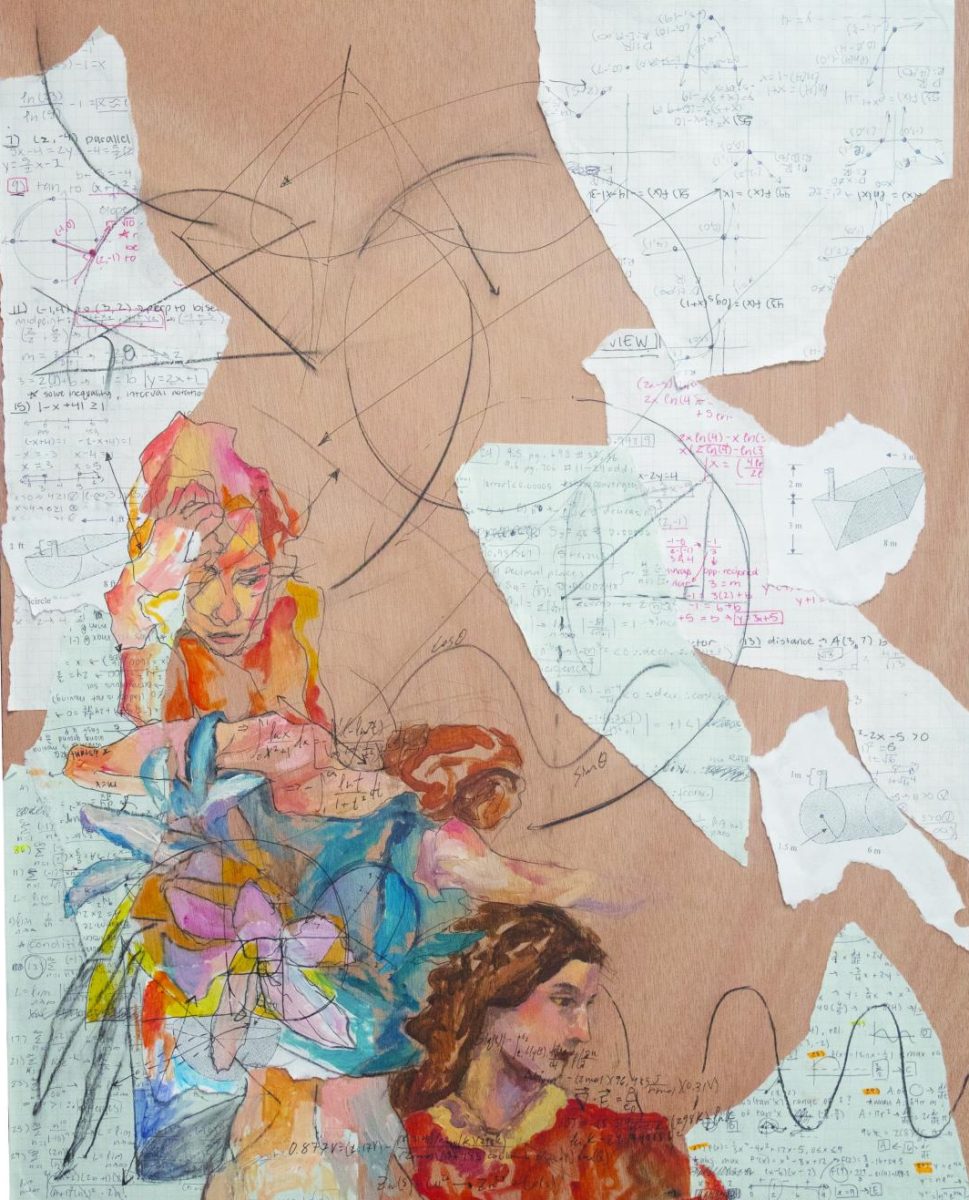

Leanne Fan (11) shared this sentiment, depressed with thoughts of the grim future the media painted. Because of this, she felt immense pressure to take immediate action, but it oftentimes felt like an impossible task.

“Before I started doing work in the climate field, I felt trapped by everything I was seeing on the internet,” she said. “It made me feel like we are past the point of no return already, and I was unsure of what I could do to make an impact on these massive problems that have been pervasive for hundreds of years.”

Porter and Fan aren’t the only ones who feel this way. According to Dr. Caroline Hickman, a British psychotherapist and researcher specializing in the psychological impacts of climate change, these global warming crises can be overwhelming to many people, leading them to shut the situation out.

“Our brains are still in the stone age,” she said. “We look at these crises coming towards us and we donʼt know how to deal with it. We just shut down emotionally. But just before we shut down, one of the things we’ll do is try and push it away [using] psychological defenses.”

Diego Ayala (12) said that encountering new information left him feeling burdened with an emotional weight and helplessly obligated to address climate change.

“I think that expectation [of addressing the issue] makes you disengage,” he said. “It’s like an out-of-body sensation where you can see the world floating beneath you and all the issues that exist and you think to yourself, ‘I should be able to fix this. There should be something that I can do to solve all these issues.’ I know itʼs a joint effort, but there definitely can be this feeling of you personally being a failure in a sense and [feeling] guilt.”

Hickman said that feelings of guilt and hopelessness are a natural reaction to dealing with the magnitude of the issue.

“[Climate change] is argued to be a hyper object, something too big to see all in one go,” she said. “We humans have never, in the whole history of humanity, had to deal with anything on the scale of the climate crisis before. The climate and biodiversity crisis is giving us 20 problems all at once and itʼs a systemic problem.”

Dr. Hickman said that humans often cope with grave situations by retreating into binary thinking, seeking comfort in extremes to regain a sense of control.

“We donʼt like anxiety,” Dr. Hickman said. “The other thing that humans donʼt like is feeling out of control. The human ego moves into trying to regain control and we either say, ‘Itʼs hopeless,’ ‘We canʼt do anything,’ ‘Itʼs an apocalypse,’ ‘Weʼre all doomed.ʼ [or] ‘Itʼll be alright. Technology will save us; it will all be fine.ʼ The trouble is neither of those binary positions are true.”

Similarly, Ayala said that although he cares about the planet, he can’t help but prioritize himself and his desires in spite of the situation, a feeling that often arises when it comes down to small things.

“Oreo is one of the biggest exporters of unsustainably resourced palm oil,” Ayala said. “I eat Oreos, but [to me], ethically thatʼs incorrect to do because I’m contributing to this system that will cause harm ecologically. I disengage out of selfishness because it can be hard to think of massive issues like these on an individual scale and we canʼt see the immediate impact of our actions.”

Ayala said the overwhelming nature of modern crises is a rising concern in today’s world. He said that when these issues are presented to the public through the media, almost every event is framed as a crisis.

“It’s a double-edged sword because almost everything has become a crisis in a sense,” he said. “The media ultimately has a paralyzing effect because you see so much and you kind of just end up being like, ‘Well, this is all beyond me, this is all happening outside of my domain of purview.’”

According to Hickman, pushing these thoughts away isnʼt helpful. Hickman conducted a study with 10,000 people who were 16-25 years old and asked them what emotion they most strongly felt in relation to climate change.

“The number one emotional response was sadness,” she said. “Young people feel sad, then afraid, then anxious, then anger, and then we get to powerless. Pushing it away doesnʼt make it go away. Facing it and learning ways to navigate it, building your resilience, and improving your relationships with other people [can let] you gain something positive out of this challenge.”

Building on this, Dr. Hickman said that rejecting this black-and-white thinking and seeing the middle ground is important when addressing the climate crisis.

“Itʼs about having a ‘both-and approach,’ not an ‘either-or approach,’” Dr. Hickman said. “When youʼve got ‘either-or,’ it’s either good or bad. But, thatʼs hard for humans to tolerate. We like to be split and clear cut.”

Ayala said that even though the flood of crises can be deeply discouraging, he believes in the importance of finding positivity amidst the chaos.

“I get very discouraged,” Ayala said. “But I personally try to look for the positive elements, especially [because] the 24-hour news cycle often amplifies the most negative voices and the most negative events.”

Dr. Hickman said that feeling strong emotions like anxiety and sadness, rather than experiencing feelings of avoidance in response to climate change is healthy.

“The Western medical model tries to treat mental health difficulties and emotions in the same way as it would treat physical health problems: suppress the symptoms, and get rid of the bad feelings,” she said. “You’ve grown up in a world that says you should not feel sad, depressed, or anxious, and if you do, there’s something wrong with you. But that advice is wrong. Feelings of anxiety and sadness in relation to climate change are completely healthy. You only feel climate anxiety because you care about the planet.”

Dr. Hickman described these feelings as a curve, in which people go through stages of emotions as they cope with climate anxiety.

“We start by feeling anxiety and fear when we first wake up to the climate crisis,” she said. “If we go through that, then we feel abandoned, threatened, despair, and a loss of control, and then we hit depression at the bottom. We just donʼt want to set up home there in the depression.”Ayala said that spiraling into depression is something very simple, especially with social media at our fingertips.

“It creates a very isolating atmosphere because you feel like the whole world is almost against the whole world and you feel like you’re not contributing to anything,” he said. “Sitting and scrolling makes me feel even worse because Iʼm still not contributing to anything.”

Moving away from the depression stage, Dr. Hickman said that people encounter a turning point that converts their anger into hopefulness and brings forth understanding and meaning. This can happen when people confide in each other about their anxieties and take action towards positive change.

“We canʼt fix the climate crisis emotionally, but we can build our own emotional intelligence and resilience so that we can navigate it better,” she said. “When people say, ‘How do you develop mental health resilience?’ This is how you do it: by going through these emotions but not getting stuck in them.”

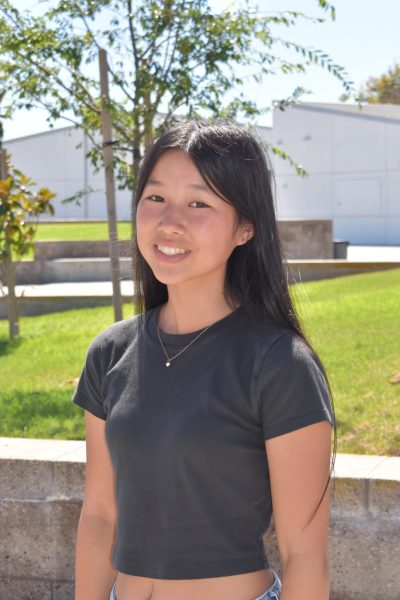

In order to avoid getting depressed while still remaining informed, Fan said that she informs herself with articles and research on what corporations and people are doing to aid climate change.

“When I do research and read about climate-related things, I try to make sure there’s a balance of what I’m reading,” she said. “A lot of articles are solely talking about the problem, which I find to be pretty depressing but something really exciting we can read about is the solutions that we’re coming up with for these problems. These not only help with feeling less hopeless and depressed about the situation, but they may also encourage other students or yourself to start doing similar things as well.”

AP Environmental Science teacher Shannon Kreamer said that talking about climate anxiety with others and spreading awareness of climate-related issues can also help students overcome hopelessness.

“I donʼt want people to block it out, or let it weigh them down to the point of depression and helplessness because thereʼs already so much anxiety in the world,” she said. “Continue having conversations, even just talking about your anxiety helps give you a sense of relief. Being kind to yourself, having awareness, and spreading that awareness is important.”

Ayala said he believes that even regular people can make a difference in the fight against climate change by making small changes in their lifestyles, which can then build up to bigger solutions.

“One of my favorite authors, [J.R.R.] Tolkienʼs, main themes is how the little things we do are oftentimes what has the biggest impact,” he said. “Big change still needs to happen, but I can see that there are definitive steps [towards bigger solutions] like iron-based batteries or things that are more ecologically friendly that give you hope for what our country or the world could potentially innovate on.”

After hearing about the ways that climate change was affecting ocean ecosystems, Porter said she researched solutions of prevalent issues and reformed steps in her lifestyle to move towards a more sustainable way of living.

“I learned different ways to help not damage the ocean as much,” Porter said. “I stopped using chemical sunscreen and I use mineral sunscreen now, which is better for your skin and the ocean, so it’s good on multiple levels.”

In addition, Porter decided to start eating vegetarian after learning about the impacts of CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations) in APES.

“The way that they took care of the animals made me really upset,” she said. “After seeing the video and how badly that impacted our environment, I felt guilty about it. That was one of the reasons why I tried [being] vegetarian, and I’ve stuck with it for a year and a half.”

While competing in international science fairs, Fan said that she has learned about the larger scale projects that other young scientists have invented to combat climate change, giving her hope for the future.

“In my community, I found so many other students and professionals working hard to mitigate the climate crisis and create a cleaner future,” she said. “During the science fairs, so many kids had environmental projects, such as using roots and fungi to filter out heavy metals or using hydros made from plant waste to retain soil moisture and help with farming.”

During these science fairs, Fan also met people from large corporations and learned of the definitive steps they were taking towards a cleaner future.

“One example of a really great organization is the SEMI-Foundation which is a coalition of around 3000 semiconductor companies. While their main goal isn’t to make an environmental change, they have noticed that they have a [big] impact on carbon emissions so they took the initiative to start becoming more green. This is really important because the semiconductor industry is a pivotal driver of our modern economy because they are used in smartphones, cities, and pretty much all technologies.”

Similarly, Kreamer said that students should think about the small-scale things that they can control that can help overcome helpless feelings of anxiety.

“Just think about what you can and canʼt control instead of worrying and fixating and losing sleep over things that are out of your control,” she said. “Right now, kids canʼt control what they’re doing on Capitol Hill or where they’re spending money on clean or dirty energy, but in not too many years, they will. There is a lot of weight in terms of making changes on the larger scale that has to do with voting and who you vote for, what their mission is, and how effective their policies are.”

According to Ayala, in the face of daunting global challenges, staying informed and actively engaging with solutions is the first step toward lasting change.

“I do think that there is real progress and I think that knowing [what’s going on in the world] is half the battle,” he said. “Doing the research [helps me] know what I can do to moderate my consumption of those things and bring awareness to these issues to create a lasting real change.”

Kreamer said that despite seeing all of the negative messages around us can evoke feelings of hopelessness, going outside and appreciating nature can remind us of the beautiful things that we are fighting for.

“Go outside, enjoy the environment, and get fresh air,” she said. “Realize that the sky isnʼt falling on you when you’re outside, and we really do have so much to be thankful for. The world isnʼt over. We have adapted over the years and we will continue to adapt.”