Finding a Place to Call Home

Hall never had anything handed to her: not even a roof over her head. For many homeless youth, housing instability can affect their academic and social success

In the summer of sixth grade, London Hall (10) and her younger niece, Skye Powell, shared a space in the trunk of Hall’s mother’s white Ford Explorer. There, they scribbled pictures in marker of the fluffy dresses they would one day own and the earth-tone outfits Hall’s mother often wore. When the sun set, they collapsed the car’s four seats, laid out a mat and blankets, and their play place became their home.

In the summer of sixth grade, London Hall (10) and her younger niece, Skye Powell, shared a space in the trunk of Hall’s mother’s white Ford Explorer. There, they scribbled pictures in marker of the fluffy dresses they would one day own and the earth-tone outfits Hall’s mother often wore. When the sun set, they collapsed the car’s four seats, laid out a mat and blankets, and their play place became their home.

This was the summer of car living and motels. The only consistency was the smell of cigarette smoke and the cockroaches that skittered across their motel room floor. On one occasion, Hall’s older sister whispered to Hall and her niece that an army of roaches would crawl into their ears and nest: so they slept in terror with toilet paper stuffed in their ears. They walked around their filthy room with their shoes on, and even in the sweltering summer heat, they slept with layers of clothing on.

It wasn’t always like this. Before, Hall lived with her father in an apartment near Sundance Elementary School. They would take weekly trips to thrift stores and Home Town Buffet. Hall said she’d pile her plate with spaghetti and before she could eat ice cream, her father forced her to eat Brussels sprouts. She remembers bravely downing both her niece’s Brussels sprouts and her own, and heading to the bathroom to spit them out before claiming her chocolate ice cream.

However, when she was 10 years old, Hall’s father left for Dubai to work at a nuclear power plant. Because her mother got injured in a car accident, her physical ailments made it difficult for her to stand and braid hair, so she soon quit her job as a hairdresser. As a result, the family struggled financially.

The summer after she promoted to middle school, Hall’s family packed up and drove to her grandmother’s house in Escondido. The two-room home seemed smaller than it was—her grandmother was a tall woman with a curly wig, who collected paintings, bedsheets, rugs, and stacks of magazines.

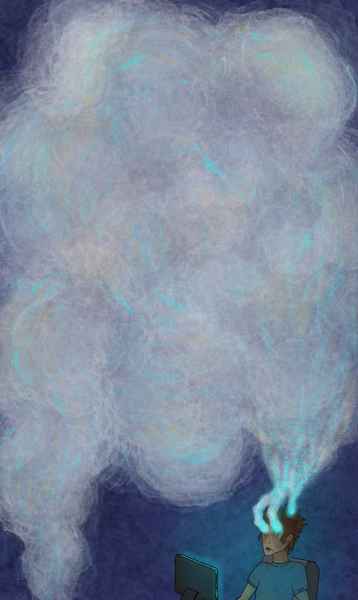

“My grandmother’s a lady who [thinks ‘it’s] my way or no way,’” Hall said. “So [my mom and her were] constantly fighting, and I ended up doing home-schooling because with [the constant fighting] I didn’t want to go [to school.] But I never attended [home-schooling] either, so when I hit high school, eventually, I didn’t know anything. I had no understanding of what was happening because I never paid attention fully in middle school.”

Her grandfather was a contrast to Hall’s grandmother. He was a portly man with peppered hair and a calmer personality.

“My grandma orders him around, and he just listens,” Hall said. “He’s very mellow. Like, when I ask for a [drive] he will drive [me]. He doesn’t talk much, but when he does, it’s like he understands how to talk to a kid more.”

Her grandfather often took Hall and Powell on trips to the dollar store. They dumped the quarters they collected on the check-out counter and asked the cashier to help them count out the change for press-on nails and strawberry shortcake ice cream bars.

In spite of the fond memories Hall had at her grandparents’ home, the fights she had with her grandmother were difficult to forget.

One day, her nephew was zooming through the house as Hall tried her best to keep up. When he was hit in the head by a door, her grandmother yelled that Hall should’ve been watching him. Her grandmother then began to scream that Hall was ungrateful and her mother didn’t raise her right. Hall’s mother argued back; her mother always fought back, until it was time to leave her grandmother’s home.

Hall then lived in her mom’s best friend’s five-room home in San Marcos. Her mom’s friend, her friend’s three boys, Hall, and her mom all lived there.

“I didn’t have a space to go or a set area,” Hall said. “There were always people near me. It was really bombarding and I never wanted to go to school.”

According to Dr. Jane L. Powers, who received her Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology from Cornell University, lacking a consistent home, like Hall, can cause academic problems and mental health issues for students. She has conducted a long-term study that partners with homeless youth to explore the nature and scope of youth homelessness.

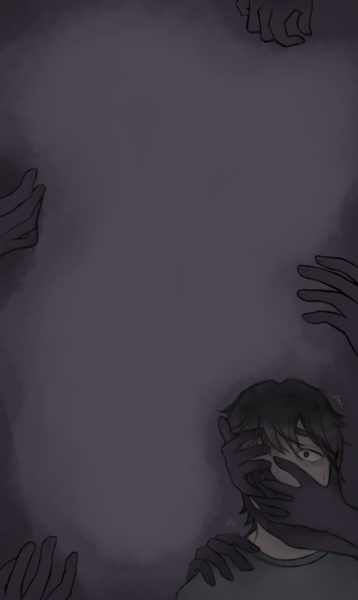

“Many students drop out of school and can’t finish high school,” Powers said. “[Some] major mental health issues [as a result of youth homelessness are] anxiety, depression, having to grow up prematurely, and not hav[ing] caring adults to support them through challenges of adolescence.”

In a study of 144 homeless youth, her team found that for those under age 21 and not currently enrolled in a high school, 21% didn’t graduate high school.

Hall had moved middle schools five different times while homeless and would often avoid going to school due to her anxiety.

“A lot of different schools are learning at different paces, so it’s very difficult to get back into the rhythm [of learning the material],” Hall said.

Laura Upson coordinates PUSD’s Youth in Transition (YIT) program, which is designed to help students, such as Hall, who lack regular residence. It seeks to make enrolling in and attending school easier for these students by providing transportation and academic support. Students who are living with a friend or other family members like Hall was, in an emergency or transitional shelter, motels, their car, and other criteria, qualify for this program.

Upson said that the pandemic exacerbated the homeless crisis in PUSD. Currently, 240 students in the district receive YIT benefits. Nine of those students attend Westview.

“The pandemic just increased the need of our families for support,” Upson said. “Many of our families lost jobs and due to that, they lost their housing, and they had to then live with either a family member or a friend, and those who are lucky are now living out of their cars, or from hotel to hotel.”

She emphasizes the importance of students helping students, as there’s nobody better to understand the needs of children and adolescents than other children and adolescents in the district themselves.

“We are always looking for donations for our students and teens who know exactly what a teen girl, or teen boy, or anyone would need,” Upson said. “You know exactly the kind of food you like, or just more than a grown-up would. [Overall,] just try to be kind. Think [whether or not] something’s happening with the student and [ask yourself,] ‘How can I help?’”

The support of intervention programs such as YIT and the support of fellow students can help homeless youth achieve stability.

“[Achieving stability] depends on whether they get help [through] service opportunities and supports to build their capacity to be independent,” Powers said. “It is possible. And it can happen. But supports are needed—youth can’t do it on their own.”

One barrier in providing homeless youth with support is effectively promoting available resources. In order to spread awareness about the YIT program, Upson said her department reaches out to teachers, counselors, bus drivers, and food service workers on school sites and encourages them to recognize and share which students could benefit from the YIT program.

Additionally, community partners such as local churches and other organizations donate and help bring awareness to the program by sharing about it to their congregations, friends, or family members.

In Hall’s case, once her father began to generate a consistent income, her mom was able to rent a house in Park Village, providing a stable home for Hall, her sister, and Powell.

“I’m still currently living with my mom and my sister, and the house [can be] very bombarded,” Hall said. “There’s a lot of people in my house, but I still have good grades and I come to school in a good mood, because I’m eventually going to move out and have my own space one day and be able to get my mom whatever she wants.”

A stable home means a stable education for Hall, which has made her hopeful she can pursue a degree in psychology when she goes to college.

“I have been at [Westview] since freshman year, so I’ve been able to catch up and [am] able to build on what I’m learning,” Hall said. “I’m taking psychology right now, and I’m going to take AP [Psychology] next year.”

With this education and maturity, the picture has faded of the innocent facade Hall’s mother once used to shield Hall and Powell. Despite this, Hall remains grateful to her mom for attempting to create normalcy in the family’s housing instability.

“My mom always tried to give me the best that she could give to me. [Even when we were homeless,] she would make it fun [and we’d go] on scooter rides. I guess seeing my mom stressed out, it makes me want to be better and go to college and have this education, because I want to be able to provide for her like she did for me.”

During the scorching summer of car living and motels, Hall’s mother told Hall and Powell that they were going on an adventure. They left for a campsite with communal showers and community activities. There was a swimming pool and most memorably, an inflatable trampoline. There, Hall first taught Powell how to do a backflip while spotting her.

“[With London,] I always have somebody I can go to that will support me and be there for me no matter what,” Powell said. “[I can count on her] for really anything that’s going on in my life, whether it be good or bad.”

Just as Hall was there to spot Powell on the trampoline and reassure her that she was safe, Hall hopes to be a constant support in her niece’s life.

“My niece is probably the main reason why I am who I am today, because I want her to see that where we come from does not define where she’s going,” Hall said. “I want her to know [that] from all of this financial instability and not having a good position with family and just being not as fortunate as others, you have to work harder, but it’s possible. I want her to follow in my footsteps so that she can see, ‘This is what she did, and I want to be like that. And I want to be happy, stable, and not in a situation that’s hurting me. I can work my way out of it even though I wasn’t privileged with the ability to have a place to call home.’”