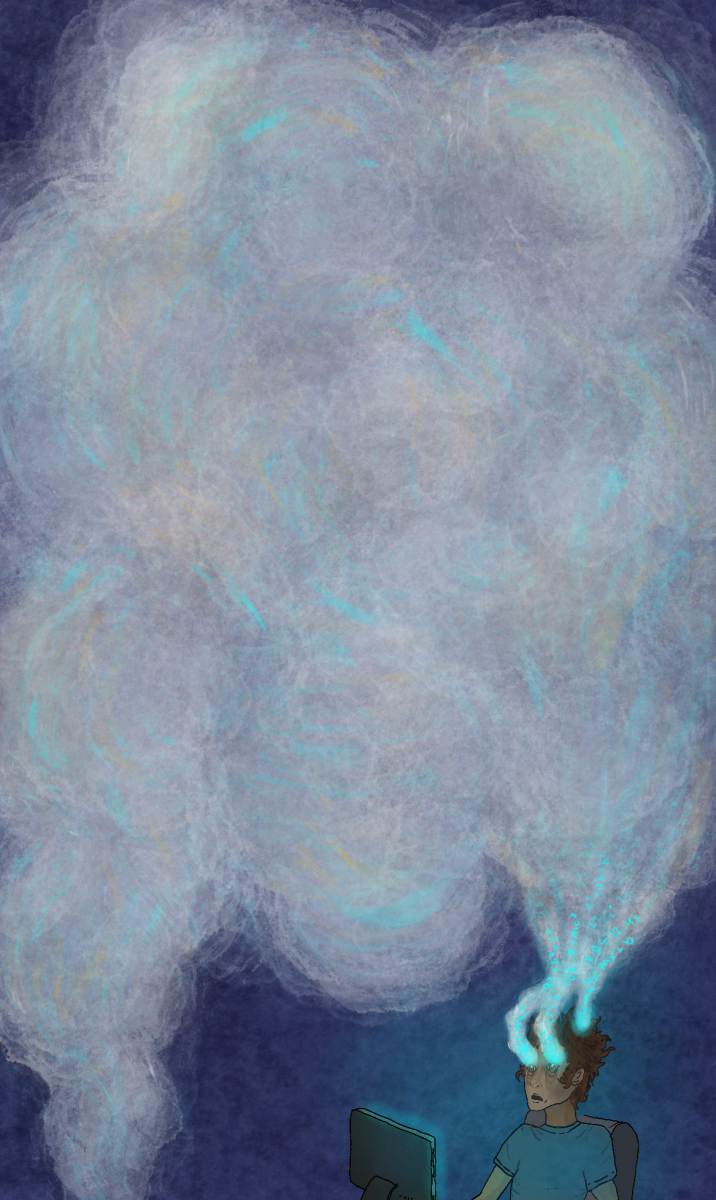

When Sophia McRae (10) goes online and starts scrolling through Instagram, what starts as a few minutes of innocent videos quickly turns into the latest reports on stories of war, violence, school shootings, and deaths. She ends up doom scrolling through people’s extreme and negative opinions on ongoing events and they build into a looming wave of negativity.

It seems like that wave subsides when her feed returns back to funny and lighthearted reels but suddenly it comes crashing down when an unexpectedly violent and negative story comes across her for you page. Many encountered this when the graphic video footage of Charlie Kirk’s assassination circulated around social media.

McRae said she couldn’t stop the flood of sensationalized violence and cynical political stances on her social media feeds, and it began to seem like nothing good is going on in the world. Unexpected graphic clips only made it seem worse. The feeling of hopelessness only continued to grow, and she would come to the only conclusion that made sense:

We are doomed.

“When you’re just seeing all this negative news and nothing else, it does start feeling really hopeless,” McRae said. “Sometimes [it] feels like all we see on the news is the wars going on, hostages, and problems in the government. I fall victim to this because I like to keep up with stuff, but it’s easy to feel like nothing’s getting better.”

The hopelessness McRae felt because of her feed is not unusual. The Harvard Business review reports that, “the relentless flood of urgent alerts, reactions, and global reports can often turn your well-intentioned scan of the headlines into an emotional minefield,” which makes it difficult for online users to find a balance of being well-informed without feeling overwhelmed by the media.

Focusing on the negative

People of all ages are spending more time on social media, according to the American College of Pediatrics, with teens averaging almost seven and a half hours online every day. In addition to this, the Pew Research Center found that nearly half of Americans receive their news from social media and perceive the news they receive as more negative than positive.

The “regular consumption of negative news, either all at once or throughout the day, can make people feel like they have ‘mean world syndrome,’ a hypothesized cognitive bias caused by too much negative media exposure that makes people feel like the world is inescapably bad, leading to emotional distress and even depression,” wrote Dr. Goali Bocci, a clinical psychologist and psychology professor at Pepperdine University, in an article about coping with negative news.

Dr. Daniel Perkins, a professor of Family and Youth Resiliency and Policy at Penn State University and researcher with a Ph.D. in family and child ecology and a M.S. in Human Development and Family Studies said he sees society’s tendency towards cynicism reflected in the negativity of our media.

“In human beings, there is a propensity to focus on the negative,” Perkins said. “And that plays out in terms of our news. The experience of violence in our daily digital dosage, whether it’s on our phone watching YouTube, TikTok, or the news, is [one which] people are seeing violence at almost every turn. If I’m spending all my time in the digital world, [I’m only] seeing a slice of reality. It’s hard for you to stay grounded.”

For McRae, seeing animosity-filled news stories made it hard to feel like there is good left in the world.

Our perception of the world is formed off of what we see and hear. But because of the media we regularly consume, Dr. Katherine Pica, a psychologist who specializes in anxiety and teaches patients Exposure and Response Prevention, believes people can interpret the world as a dangerous and frightening place more than it actually is. The Pew Research Center reports 64 percent of Americans believe social media has a mostly negative effect on the country.

“The media can skew [your] perception of the world being horrible,” Pica said. “Dangerous things happen, but frankly, not quite as frequently as what is ingested in social media. [It can] leave people on edge because our brain is reacting like it’s happening to us right then and there [which] can cause anxiety.”

Even when we see positive things online, our brains quickly let them go as the next big dismal headline flashes across our screen and our attention is shifted to whatever pressing issue is being presented to us.

“The brain quickly lets go of positive things,” Pica said. “It’s skewed towards receiving negative information out of our instincts for fight or flight responses to protect itself. When we were hunters and gatherers, we needed to look [for] negative things in order to survive. The problem is that brain structure is still the same today, and our brain is tilted towards negativity but it’s not healthy to notice negative things all the time. People [end up] ruminating about things like war, climate change.”

David Jang (12) said he experienced seeing positive stories every once and a while on his feed, but they quickly faded away as people’s attention shifted back to pressing issues.

“Optimistic stuff does go viral, but then gets forgotten in an instant because we’re just so sucked in with all of the other things happening around us,” Jang said.

A lack of control

Jang’s lack of control when it comes to optimism on his feed is not uncommon. The Pew Research Center reports that only one in ten people feel like they have control over what they see on social media. The internet and social media are helpful ways to stay informed, but the American Psychological Association found that many teens and young adults experience stress directly related to news they saw on social media.

Recently, the assassination of Charlie Kirk, a conservative political activist, overtook the news and social media. Graphic video footage of Kirk being shot in the neck circulated the internet.

“I wasn’t able to escape it at all,” Jang said. “I just started scrolling, and then I’m getting four reels in a row [about it]. I love listening to different opinions, but I’m constantly seeing people trying to convince me that I should believe that and not the other side. It’s very overwhelming because I can’t control [what] shows up on my feed.”

When Jang started to realize how he would be swamped by stories on his feed, he would try to take time off of the internet and social media, but found that it felt like he was missing out on the latest news and falling behind on timely events.

“When I’m not getting all this negative news, I feel this slight sense of guilt that I’m not up to [date] with events,” Jang said. “Negative news stores in my brain and becomes more baggage. I [want to] learn about stuff

but not be so sucked into it that I can’t get anything done.”

For McRae, repeatedly being shown videos like Kirk’s assassination on her feed made the topic feel more intense especially because she often didn’t even have a choice whether or not she saw those videos. In one of Mayo Clinic’s podcast episodes, Dr. Adam Anderson, a clinical psychologist said that viewing a video online has a more shocking and emotional response than just reading about the same thing, especially if it comes out of the blue.

“Things are sensationalized and seeing the same things over and over and over again can make the problem feel bigger and more imposing,” McRae said. “There can be really good aspects to keeping up with things, but because you’re reading all this negative news and you’re not seeing anything else, it does start feeling really hopeless and like you never see anything good. You want to be aware of things, but there’s a point where you can become too aware and it’s more detrimental than helpful.”

A need for balance

Dr. Pica said that balancing our media intake doesn’t have to mean completely going off the grid, but each person can handle a different amount of negativity, so they have to find a balance that works for them and their emotional wellbeing.

“It’s not an all or nothing; that’s unrealistic,” Pica said. “But being mindful of how much social media or content we’re ingesting is important. Everybody’s threshold for negativity is going to differ, so it’s really important [to] check in with yourself and how you feel after consuming negative media.”

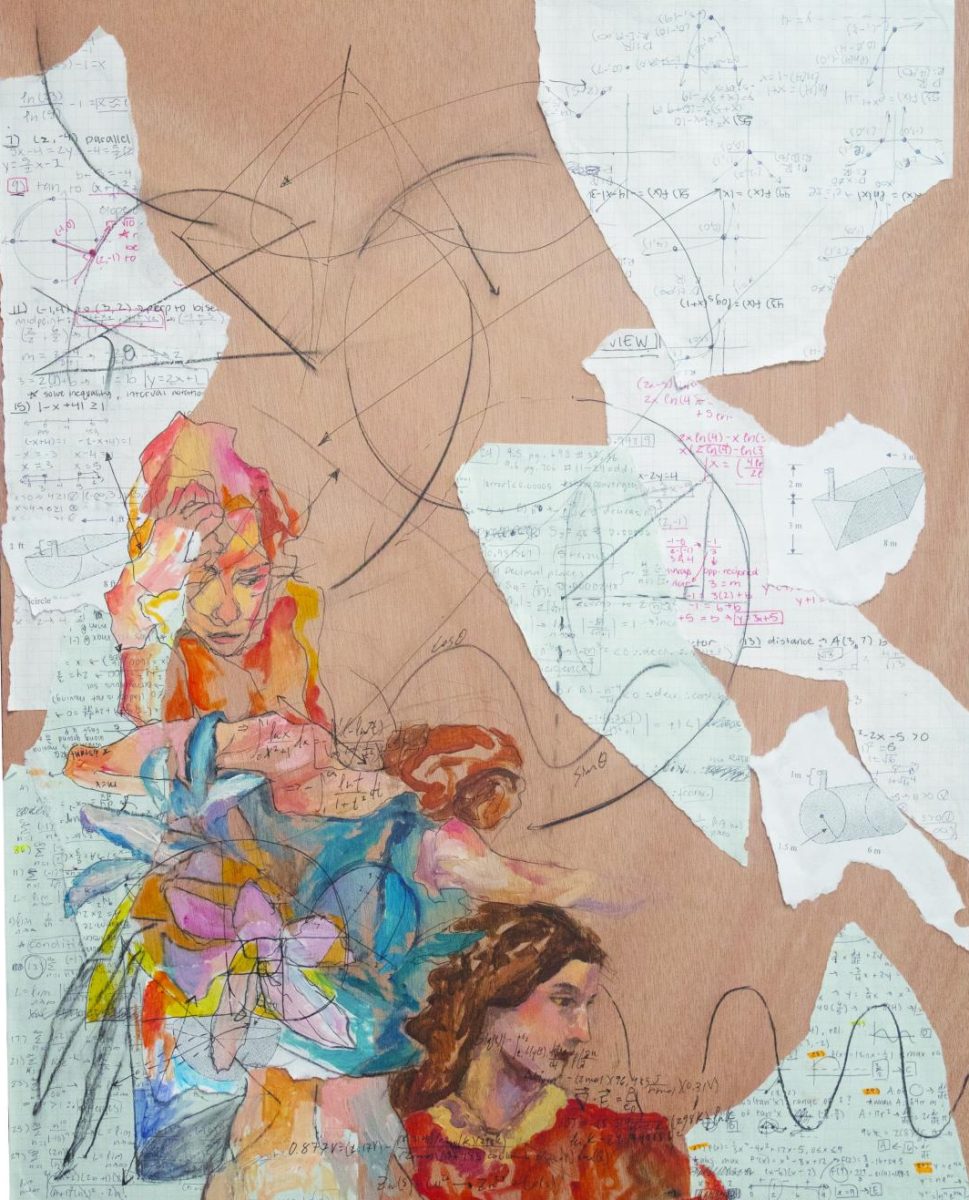

McRae found it helpful to practice seeing the positives in the media she saw by trying to understand the full picture and acknowledging what is called “negative bias,” or what Psychology Today describes as the brain’s tendency to think about negative topics for longer periods of time. She said it eased the mental burden negative news stories placed on her shoulders.

“There’s value to understanding and seeing the positives,” McRae said. “[It’s] important that we understand that the positives don’t necessarily neutralize or outweigh the negatives. Balance lies in seeing problems, feeling some type of way about them, but understanding that it isn’t all doom and gloom.”

For Jang, addressing that feeling of helplessness and anxiety comes with discipline. Letting himself process negative media and pausing before reacting helps him to lower his stress and avoid overreacting.

“When you’re going so fast, lingering on something without acting is a very important skill we often forget,” Jang said. “When you look back at issues and just wait, it gives [you] more time to be decisive. Your reaction that instant is gonna be vastly different than what you think 24 hours later.”

Being in the now

Jang said he realized that staying present in his daily life was an important part of staying grounded. He found talking with his friends and family not only about pressing the issues he saw online would help him cope with what he saw. Dr. Pica said that we have become substantially more isolated because of online platforms like social media.

“Being on [social] media gives us this illusion that we’re connected to people,” Pica said. “Might it be easier just to stay home and scroll on social media and spiral? Yes. But having in-person conversations with people is so important. People are there for us and able to handle what we’re going through [more] than we actually think [they are].”

Dr. Pica said that taking the time to be in the moment and focus on what you can control can shift your mind to the good things.

“It’s important to refocus your attention to what things you can change [and] what is within your control,” Pica said. “If you’re always focused on the things that are out of your control, [it is easy to] feel hopeless.”

As a community, focusing on supporting each other through overwhelming politics or the stress of war creates a system that helps us cope and deal with problems together, Dr Perkins said. He emphasizes a balance between screen time and face-to-face human interaction

“Computer time and screen time is important; it’s a good way to learn, an opportunity for us to engage, so that’s a good thing,” Perkins said. “But there should be limits to it. We [have to] create experiences that move people away from an inundation of violence and negativity. You should be interacting with your mates, having a good laugh, telling a good joke. [Then] you’re less likely to succumb to the pressure and to the negativity, [so] you bend but not break.”

Jang said he feels more in control of his life when he spends time off his phone.

“We can always do more with putting away our phones,” Jang said. “I have other hobbies like cooking and reading, and it’s kind of like escapism. I feel a little bit more in control. It’s a very empowering thing for me, knowing what I’m able to control and not control.”

Not only can grounding yourself in the present help you overcome that feeling of helplessness, but Berkeley’s Greater Good Magazine found that seeing the good in people makes you begin to consciously seek out the good in situations. McRae said she felt more content when being around her family and friends doing things she loves.

Despite all that she sees online, McRae said she has learned how to regain control when she falls into cycles of hopelessness.

“Taking a step back and being in the right now, [realizing] what’s going on around me, what I actually concretely see, makes me feel calmer and [less] disconnected,” McRae said. “When I’m hanging out with my friends or when I’m writing or playing piano and doing things that take my attention and that I enjoy doing, that’s when I’m free of the most anxiety because it makes me here in this moment, in the present.”