Cutting Ties: Misinformation Severs Bonds

False information and conspiracies strain students’ relationships with loved ones

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, with cases surging and schools scheduled to reopen, Eileen* wanted to get vaccinated. She believed it was her duty to help curb the virus’ spread, to do whatever she could to lower transmission and potentially save lives. But despite repeatedly asking to, Eileen was unable to get vaccinated until months later. As a minor, she needed parental consent, something her mother wasn’t willing to give.

Eileen’s mom didn’t believe in the vaccines, or the threat COVID-19 posed. She believed that the vaccine contained microchips to track people who received it, and she was convinced that the infection rates and statistics were all made-up.

“All the family arguments kind of stem from the election of 2020, and the COVID vaccine also came then,” Eileen said. “It’s really hard for me to blame my parents though, because of their educational background. My dad was impacted by the Chinese Cultural Revolution and didn’t finish high school, and my mom went to a lesser-known college, so it’s really easy for them to fall into misinformation—especially my mom, who was already into extremist organizations like QAnon.”

Eileen grew up in Pennsylvania. After her mom’s near-fatal car accident, Eileen’s family joined the local Chinese-Christian church there.

“After [the accident], her friends told her God saved her and that’s when we started going to church,” Eileen said. “She got really involved, and everyone that surrounded us had really conservative views, so she became rooted in conservative-Christian ideals that matched up with conservative right-wing politics. She’s a firm believer now and justifies all her arguments to the Bible and God, which just doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

When the family moved to San Diego in 2017, the local Chinese-Christian church they joined had left-leaning political views—liberal viewpoints that Eileen’s mom believed went against her faith.

“I would tell her that the people at church believe in Jesus and that they aren’t homophobic,” Eileen said. “And she just said they aren’t real Christians. She told me I couldn’t go to that church anymore, so I eventually just stopped, and she distanced herself from that church as well and reconnected with her conservative friends from Pennsylvania.”

While surrounding herself with a close group of right-wing extremists, Eileen’s mom started to believe that Joe Biden’s inauguration was staged, that it was filmed in Hollywood, and that Donald Trump was going to come back to office.

“I try to explain my side and my viewpoints, but she just rejects them,” Eileen said. “There’s almost no point in addressing her beliefs now, because whenever I explain how it logically just doesn’t make sense, like QAnon and the idea that liberals have a federally-operated pedophilia ring, she just never gave in. I try to not talk about religion or politics, but she always brings it up and it just results in an argument and I end up saying that she can have her own opinion and I’ll respect it if she respects mine.”

According to Eileen, the language barrier and her mom’s consumption of biased news sources heavily contribute to her mom being misinformed and the conflicts that result.

“My Chinese isn’t very proficient and if I want to really be convincing and communicate something, it’s really hard,” Eileen said. “I can’t get the message through and as my mom immigrated from China, her English isn’t good enough for her to understand my arguments in English. So then the news she consumes and the people she surrounds herself with play a huge part, as it doesn’t really show her any other perspectives.”

Joshua Tucker is a professor of politics at New York University (NYU), the Co-Director of NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics, and the co-editor for The Washington Post’s politics and policy blog. His research has explored polarization, misinformation, and the effects of social media on political knowledge.

Tucker said that a valuable solution to prevent others from falling into the pitfalls of misinformation is to correct it when encountered.

“For example, if you see something on Twitter saying that vaccines cause infertility and you respond saying ‘No, actually here’s a study showing that they don’t cause infertility,’” Tucker said. “That may be really helpful, not for the person who posted it, but for the other people who are reading it and watching [those interactions and posts].”

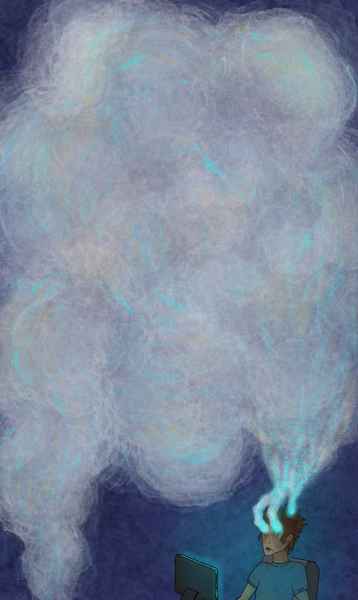

But for people already within echo chambers, Tucker said there is no simple answer. Over quarantine, Eileen’s mom began watching a YouTube channel with Chinese creators who promoted themselves as anti-communist. The channel’s videos supported American right-wing extremist perspectives, such as the idea that liberal politicians, Biden and Barack Obama for a few, are involved in child trafficking.

“She watched it [the YouTube channel] religiously,” Eileen said. “All the propaganda made her viewpoints a lot more serious because the media consumption was so frequent. ”

Jackie Otala is a graduate student at Clarkson University and researches the polarization caused by social media and misinformation. She recently co-authored a cross-national research paper studying the effects of COVID-19 misinformation in the United States, China, and Iran. Otala said that one of the causes for the rapid spread of misinformation is the difficulty in regulating it online, particularly in different languages. [Text Wrapping Break] “Language processing for languages other than English is not to the same standard as it is for English,” Otala said. “Facebook, for example, has been really far behind in putting resources into fact-checking for other languages, which doesn’t really make a lot of sense because so many people in America speak different languages, so that basically results in misinformation being more prevalent in other cultures [living in the United States].”

Her research found that misinformation hurt minority groups in America more, with greater rates of vaccine hesitancy due to a lack of widespread, accurate information. A recent study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania of 10,871 healthcare workers found that in comparison with White healthcare workers, vaccine hesitancy increased nearly five-fold among Black healthcare workers, two-fold among Hispanic and Latino healthcare workers, and nearly 50% among Asian healthcare workers.

However, regulating misinformation in multiple languages is difficult. Some companies, such as Meta Platforms Inc., a multi-technology company with subsidiaries such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp have outsourced fact checking and information monitoring to other companies. Otala said that the databases used to conduct wide-scale information monitoring and fact-checking of certain languages have a limited capacity.

Due to this, Otala said that it’s far easier to become misinformed and fall into the trap that algorithms have been designed to create.

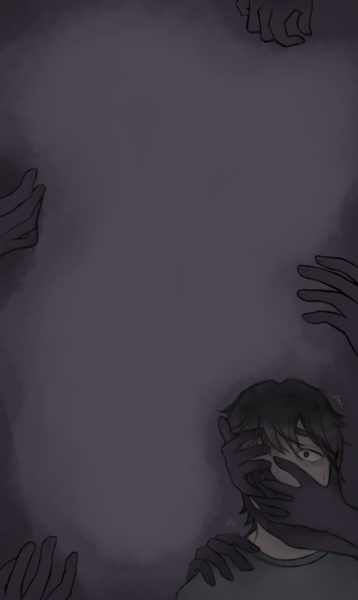

“A lot of people think they’re smart enough that they won’t fall for it until they do,” Otala said. “You engage with [misinformation] more and more until you’re falling down a rabbit hole where you think the Earth is flat and there are microchips in the vaccine. It’s a very slow process, but ultimately, I think it has a lot to do with recommender systems. [Misinformation] sounds crazy when you look at it from start to finish, [all at once], but each step of the way is far more subtle.”

Each subtle step, while seemingly harmless, can easily turn into harmful misinformation. Tucker said that one type of education to proactively combat misinformation is digital literacy.

“Teaching people who are newer to the Internet especially how to know trustworthy sites from not trustworthy sites can help,” Tucker said. “Like there’s a browser extension called Newsguard that lights up when you go to click on a news source, or on your Facebook page. It’ll show green if it’s trustworthy and red if it’s not.”

Unfortunately, with Eileen’s mom, the misinformed beliefs escalated and believing COVID-19 wasn’t real came at an irreplaceable cost.

At the beginning of winter break, Eileen was told her grandparents had pneumonia. On the day after Christmas, she was told that her grandmother had passed away.

“Around two weeks after my grandma passed, my grandpa got admitted to the ICU,” Eileen said. “Right after school, out of the blue, my mom told me that she had something to tell me but that she didn’t think I could handle it— that I couldn’t handle the truth. It seemed like she was hesitant, but I asked her to just tell me, and she told me my grandma had died from COVID and that my grandpa has it too. And that really angered me, because she was undermining the severity of it.”

Eileen had visited her grandparents during Thanksgiving break when they were both healthy.

“My mom got sick during the time [we visited them],” Eileen said. “When we left, my grandparents got sick and never recovered. I can’t completely pinpoint the fact that they got COVID from my mom because she never got tested, but I always think about how things would have turned out if we didn’t visit them—if we didn’t have them be more exposed to the virus than usual.”

While the types of misinformation and its effects encompass a broad range, Otala said that the deadliest has been health misinformation, particularly underscored by the pandemic.

“In an election, the effects of misinformation don’t feel as direct,” Otala said. “Whether Trump lost the election or not didn’t directly kill a lot of people, but COVID misinformation does, and that’s the huge eye-opening part of the pandemic. The internet is far more powerful than one may expect; just people who read an article online could have the whole course of their life changed, or the whole course of lives around them, because ultimately, you’re dealing with a deadly disease.”

Otala said that misinformation’s second-largest impact has been seen through the deterioration of relationships.

“Some people have lost their entire family because they think they’re crazy—because they fell into a rabbit hole on YouTube or Facebook or WhatsApp,” Otala said.

For Jordan*, whose Vietnamese grandparents raised him alongside his siblings, misinformation took a toll on their relationship.

“Their news comes from very religious news sources, Vietnamese YouTube channels, and Fox News,” Jordan said. “I still love them, but you just lose some respect [for them] because of how they go about things, and you can’t really say anything, especially because they’re your grandparents. Whenever we have family gatherings too, the differing political beliefs always makes it a little uncomfortable.”

Jordan said he believes that both the conservative Vietnamese and English news consumed by his grandparents on a daily basis only amplified their subscription to extremist opinions, worsening through the language barrier. One such news source is One American News Network, from which Jordan’s grandparents developed anti-immigrant sentiments despite being immigrants themselves.

“It’s so confusing for them to go against something [immigration] that benefits them, but I think [extreme-right beliefs] really originated from the fact that they were so religious,” Jordan said. “They were entering a completely new country, and one of the ways they were able to find comfort was through religion, so they found their home in a specific subset of Vietnamese-Catholic people. Over time, that group of people inherently became more and more conservative, and those beliefs just sort of spread and the news really just propagated that too.”

For Alex*, one of Jordan’s siblings, their grandparents’ beliefs ended up forcing them to hide and avoid accepting a large part of their identity—their sexuality.

“When you think of family, you think of something that’s a safe space, something that’s welcoming,” Alex said. “But knowing where my grandparents’ religious and political beliefs lie, I know that isn’t the case. The idea that their love is unconditional, that’s a belief I have to know isn’t true. Not because I think my grandparents don’t love me but because of the idea that it’s [being gay is] sinful, and the misinformation politically means that I know there is a condition.”

Alex and Jordan grew up in the Vietnamese-Catholic church that their grandparents would take them to. Because they were first-generation immigrants, language differences persisted. Their grandparents were unable to effectively communicate in English, while Alex and Jordan were unable to speak Vietnamese fluently. But they found a connection through religion, a connection that was later severed.

“It’s hard to come to terms with the fact that something that is one of the best ways to connect with and to interact with someone you’re so close to familialy has been the source of so much misinformation,” Alex said. “And when it comes to sexuality and other parts of your identity, it’s a difficult thing to reconcile because on one hand the Catholic Church offered my extended family a safe haven as immigrants, and on the other hand, its teachings are directly saying that people who are gay are sinners—destined to eternal damnation.”

Alex and Jordan attribute most of their grandparents’ misinformation, now, to the media and the politically extremist podcasts they listen to, while at the same time acknowledging the large role their grandparents have played in their lives.

“I really do love my grandparents,” Alex said. “They cared for me, they raised my siblings and me right alongside my parents, and I’ll never be able to repay that. But regardless, I have to reconcile their harmful beliefs with my identity.”

Likewise, misinformation has greatly affected Eileen’s relationship with her mom and family.

“Honestly, it’s really sad,” Eileen said. “It’s really sad to see what misinformation, and not being informed, does. It takes a toll on family relationships. In the end, I try to tell myself that life isn’t all about politics and your opinion on religion. But regardless, I’ve realized the importance of politics, how important it is to care about what’s going on and the importance of awareness and education.”

*Names changed