Broadening the Mind

By speaking multiple languages, bilingual students recognize cultural differences whilst improving cognitive functioning.

In the middle of eighth grade, Gavin Jin (12) moved to the United States from China. Despite having grown up learning English as a mandatory class, simply recognizing words in English was insufficient to understand the new world around him. The video games his classmates talked about, the shows they watched, and even the Bill Nye documentaries that he was shown in science class were foreign to him.

“My first language is Mandarin, but I grew up watching Disney movies,” Jin said. “Hollywood was really big worldwide, and we used to watch English movies with subtitles. It was very common, but when I got to America, some people only spoke English, so they’re used to not watching with subtitles. They don’t like it. They said it was not good. But it was something that was normal for us, like learning two different languages.”

After moving, Jin said he struggled to adjust to the new culture that accompanied a predominantly English-speaking setting. Over time, with greater exposure, Jin acclimated.

Jin speaks Mandarin at home, and English outside his home. Similarly, Emilia Mirea (11) converses in English at school, but when she arrives home, she speaks Romanian with her family. Mirea’s native languages are English and Romanian, and she has taken Spanish classes. She has been introduced to a variety of cultures and ways of life while learning these languages.

New Perspectives

“A big benefit [from learning languages] is that I feel more culturally [aware],” Mirea said. “[I] can understand cultures better and have an understanding of people’s differences, so I can judge them less. I judge less when I hear of different traditions or habits, and I’ve become more invested in [news] from other countries, which allows me to be more aware of what’s happening around me.”

For Jin, one of the most challenging aspects of adapting to a new language was the difference between Mandarin and English pronouns.

“In Mandarin, all the pronouns are kind of pronounced the same,” Jin said. “He and she sound the same, and in Chinese, there’s not really a gender-neutral pronoun that people can use [when speaking]. So it’s kind of a problem in many language systems, but with English, there’s he, she, they, and other pronouns to use. So that difference really changed my perspective [on modern pronoun usage].”

Dr. Ping Rochanavibhata researches bilingualism at the Northwestern University School of Communication. Her research has shown how knowing multiple languages can change one’s perception of others.

“Being exposed to more than one language can improve communicative and social skills,” Rochanavibhata said. “Specifically, bilingual[s] are able to consider people’s perspectives and discern what information they have and do not have. This comes from the fact that when you’re bilingual, you always have to keep in mind which language to speak to whom, and what to speak at certain times and places.”

This understanding of people’s varying viewpoints helps Mirea recognize Westview’s diversity.

“I understand more about people, how diverse Westview is, and how different people can be,” Mirea said. “In every culture, people have different ways of treating each other when they first meet. When I was in Peru, I noticed that everybody treats each other as family, but in America, everybody sees each other as strangers. So I started to understand why people act the way they do [based on their backgrounds]. Because I know that every culture is different, I cast less judgment [on people] and I am more accepting of people’s actions.”

Hidden Benefits

Dante Burrellmedley (11) is fluent in English and Japanese. Though Burrellmedley speaks both languages often, he tends to think in Japanese. While some might believe thinking in a different language would make things more difficult, especially while he’s in an American school, he said he believes it is actually helpful in some ways.

“Doing math while thinking in Japanese is way easier,” Burrellmedley said. “An example is multiplication. There are ways to say it in Japanese that make it much easier to remember.”

According to Rochanavibhata, fluency in any two languages is also known to improve standardized test scores in reading and in math for young students.

“Work has shown that being bilingual does influence performance in school,” Rochanavibhata said. “Bilingual students performed better on math and reading than their monolingual counterparts.”

Mirea says that learning a third language has benefited the way she approaches learning new concepts, both in and out of the classroom. Her skills involving improvising and adapting to unfamiliar situations have been improved.

“Before I got familiar with three languages, I was just thinking how a book would state [things], with straightforward thinking,” Mirea said. “Now, I can think more creatively and out of the box. [For example,] I’ve noticed that many kids feel their cultures are not important or heard. [To help reduce this] I am starting a club to introduce music from different countries, and I want to choose songs that are culturally important [to share with different people].”

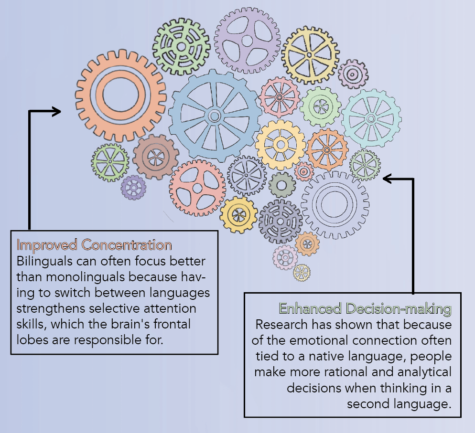

Having to mentally switch between languages increases executive functioning and creative skills, as those parts of the brain are active with language use. Rochanavibhata’s research has shown that the cognitive abilities of bilingual people change on a fundamental level, as their brain makes the switch between two completely different sound systems, sentence structures, and grammar rules.

Dr. Mark Antoniou is an associate professor at the MARCS Institute for Brain, Behavior, and Development at Western Sydney University. He has researched the correlation between language use and cognitive behaviors.

“It is thought that because bilinguals have to switch between languages depending on who they are talking to, they also show an advantage when switching between other concepts that have little to do with language,” Antoniou said. “They are able to use abstract knowledge and see associations that are not immediately apparent.”

Mirea must switch between languages to speak with different people, but for her, this doesn’t make conversation much harder.

“Sometimes [there are] specific words I want to say in English, but I won’t know them in English,” Mirea said. “[But] I can still communicate [in English] with my friends easily.”

In the past, it was common belief that introducing multiple languages to people at a young age, like with Mirea, would cause developmental problems. Parents would avoid speaking multiple languages in order to avoid the risk of confusion and developmental impediments.

The Neuroscience

“It was once thought that exposing children to two languages would confuse them and lead to language or cognitive delays,” Antoniou said. “The parent or teacher may be concerned that they should focus all of their energy and attention on learning the language that ‘matters most,’ usually English. But this is based on false assumptions, and there is no evidence of this whatsoever.”

Moreover, there is no risk of speech impairments when learning multiple languages from a young age either.

“Learning two languages doesn’t lead to any sort of speech impairment or impediment,” Rochanavibhata said. “You might hear anecdotally that, for example, bilingually exposed children may start speaking later than their monolingual peers, but this is not permanent.”

In fact, bilingualism causes changes in the brain that can prevent the severity and onset of neurodegenerative diseases and other problems later on. According to Antoniou, a layer of protection is added to the brain with the acquisition of a second language, and though it may not entirely prevent problems with mental function down the road, it can prove to be a significant buffer against symptoms.

“Bilingualism or learning a second language leads to an increase in gray and white matter,” Rochanavibhata said. “This basically [means] that you’re protecting your brain from cognitive decline.”

While bilingualism provides tangible evidence of brain development in the increase of gray and white matter, it also leads to enhanced interpretive abilities that aid in the translation of foreign languages.

“I feel like I already have skills [from knowing two languages] that help me interpret what other people are saying [in languages I don’t speak],” Burrellmedley said. “Because I know English and Japanese, I think I already have the skills to make it easier to understand Korean and Spanish, [for example].”

Beyond the Present

Mirea said she believes that learning a new language is worth the time and effort required to master it. Recently, she has taken Spanish classes to learn a third language.

“Not only can you talk to other people, but in a way, you’re closing your doors if you’re just restricting yourself to one language,” Mirea said. “[To me] it feels like common courtesy to learn at least one more language.”

A common misconception is that adults struggle much more than adolescents and children while learning languages. While in some areas, they may be less proficient, in others, they have advantages.

“Adult language learners can become fluent because they’re able to use their existing linguistic skills,” Rochanavibhata said. “It’s never too late to learn a second language.”

Knowing two languages and learning a third has influenced Mirea’s life for the better.

She finds strength in being able to understand people from different backgrounds.

“I’ve become more confident speaking more languages,” Mirea said. “It’s a new way to see the world.”