Body-Mind

Through media consumption, students develop skewed self-images

Alexa Litchev (11) constantly felt like she wasn’t good enough. She believed that social media, movies, the fashion industry, and most everything around her screamed she wasn’t skinny enough, wasn’t healthy enough, wasn’t perfect enough. Unaware of the deceptive nature of diet culture, Litchev began to compensate for all of what she perceived to be her flaws that the media repeatedly pointed out to her.

This lack of self-worth was just one of the many ways Litchev was impacted by diet culture. It was an impact that led her to have an eating disorder. According to the American Psychiatric Association, eating disorders are behavioral conditions causing persistent interference with eating, often originating from psychological implications.

Her eating disorder was characterized by a hyper-focus on food and exercise in a way that ended up harming her body. She first started experiencing the adverse effects of diet culture during her freshman year of high school.

“I feel like the teenage years are often when people start trying to change their bodies to fit societal pressures and the ideal body,” Litchev said. “For me, I was definitely influenced by social media [platforms like] Instagram and TikTok. My whole entire feed was flooded with thinner bodies and fitness videos, and even when I tried to unfollow them, they just kept coming up.”

These constant portrayals of thinness from social media, especially from the modeling industry, eventually started taking a toll on her mental health and body image.

“Diet culture definitely caused a lot of disordered eating and damaged my relationship with exercise,” Litchev said. “I was not having a healthy mindset towards food or exercise; I was using it to compensate.”

Inspired by the media and the people around her, when Litchev was in ninth grade, she tried to follow the keto diet in an effort to fit in with what was being mainstreamed. The keto diet forces the body into a state called ketosis by cutting out carbs from the diet and replacing them with high-fat foods, which drives the body to burn fat as energy, instead of carbs.

“I didn’t necessarily follow it super strictly, but I did start trying to cut out my carbs in order to lose weight,” Litchev said. “It was definitely unhealthy and it led to binges because obviously, you can’t really live without carbs; it’s your body’s preferred source of energy.”

Ethan Woelbern (11) also struggled with restricting his diet due to living in an environment where thinner bodies were embraced.

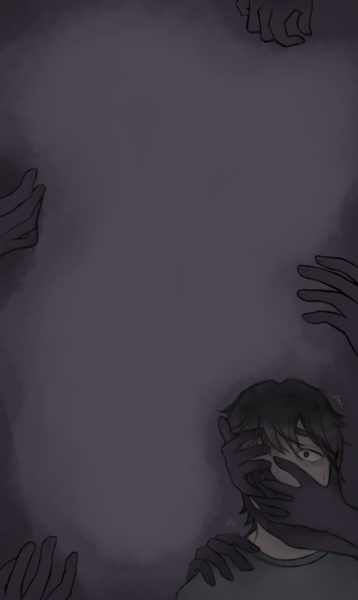

“Diet culture affected me when I was younger, especially in seventh grade,” Woelbern. “I felt like I was too big and I wanted to be more slender. I started watching a lot of YouTube videos on how to lose weight or how to look a certain way. Once you started watching one video, you couldn’t stop watching them. You start going down rabbit holes and it’s a never-ending cycle.”

Litchev said that the largest influence on her negative body image was the fashion industry. Clothing companies only showed the clothing on extremely skinny models, creating an unrealistic expectation for what the clothes would look like.

“I feel like people just blame their own bodies for clothes that don’t fit them and that’s what happened to me,” Litchev said. “For example, with Brandy Melville [they use] ‘one size fits all’ marketing. I can fit into a lot of Brandy Melville clothes, but I was upset that I didn’t look like the Brandy Melville models that I saw on social media. I feel like these unrealistic images display messages associating fitness with attractiveness, and for me, I thought in order to be seen as attractive or healthy, I had to meet a certain body ideal, even though it wasn’t healthy.”

Kay Rhee is a doctor at Rady Children’s Hospital, who runs the Medical Behavioral Unit, which is an inpatient eating disorder unit.

Dr. Rhee said that given the current obesity epidemic in the United States, diet culture is especially prevalent. This can, however, cause dangerous problems for those with specific genetic predispositions that cause them to be more likely to have an eating disorder. Though scientists have not come to a conclusion on a specific chromosome that causes eating disorders, Dr. Rhee said that it is most likely chromosome four, 11, 13, or 15.

“About a third of children are either overweight or obese and two-thirds of adults are overweight or obese,” Rhee said. “So it makes sense for everybody to talk about trying to eat healthy and dieting, but because that is so pervasive, it can have detrimental effects for the kids who are more biologically primed to have an eating disorder. When those kids are in that culture, they are able to take it to the extreme. They’re biologically driven to restrict their caloric intake, but the culture around them feeds into it. They feel like ‘I should be doing this because there’s an obesity epidemic and I need to eat healthy.’”

For Woelbern, his eating disorder was mainly caused by his perfectionism.

“It was one thing where I felt like it was easy to control: stop eating as much,” Woelbern said. “It sounds difficult but at the time, I was so focused on having something to control.”

Though the specific causes for eating disorders differ from person to person, Rhee said eating disorders are often triggered by a stressful event in someone’s life. The person then finds it comforting to have control over what they’re eating.

“It’s not just society that is the worst influence—there’s such a biological drive to this stress,” Rhee said. “The transition to high school is hard, and junior year and senior year of high school are stressful years too. [Things like] trying out for a sport, being rejected by your friend group, bullying, divorce, job loss; any kind of stressful event is often where we start to see things deteriorate.”

Because of the large amounts of stress adolescents experience, eating disorders are more common than one may think. According to a study done by the National Eating Disorders Association, about 9% of the U.S. population is expected to have an eating disorder at some point in their lifetime. Despite their prevalence, Litchev said that they are not often discussed, but without talking about eating disorders, she said it’s easy to fall into the traps that society sets.

“It’s very easy to fall into habits without even realizing it because eating disorders are such a stigmatized and sensitive topic; no one really talks about it,” Litchev said. “There isn’t that much preventing you from accelerating these behaviors over time.”

Even though eating disorders are often a sensitive topic, Rhee said it’s essential that we expose the concept to children and adolescents to ensure that the problems can be prevented or treated before they are too severe.

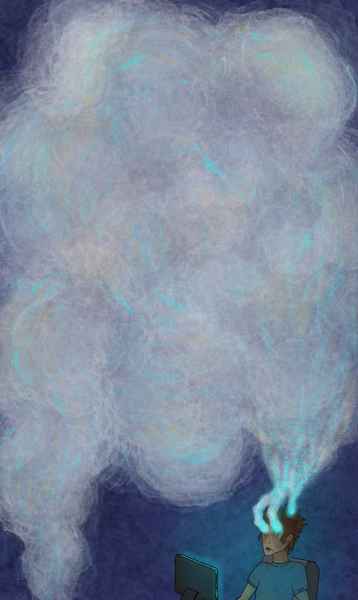

“From a treatment perspective, we know that the earlier you treat it when the kids are younger, the more likely you are going to be successful at managing this eating disorder and getting rid of it,” Rhee said. “If we don’t address it and start to recognize it earlier, we’re actually making it more difficult for them because the longer you have an eating disorder that’s untreated, the harder it is to get better. If you let it linger, it almost becomes like a bad habit, and the longer you have it, it hardwires the brain to start to think a certain way and it’s really hard to break those connections.”

Though females are affected by eating disorders disproportionately, men go through the same struggles, often worsened by the fact that it is uncommon.

“It’s usually a 10-to-one ratio,” Rhee said. “The difference is how society views it. They view this as a female disorder, so the boys who have it almost have more shame about it, because it’s ‘not a male thing.’ It can be almost harder for the boys because it’s harder for them to connect with people.”

Woelbern struggled with this when at an eating disorder clinic He struggled to connect with others.

“At first I was kind of nervous because I felt like I was going to be the only guy there,” Woelbern said. “There were a couple of other guys there, so that kind of helped, but ever since then, I haven’t really encountered any guys with eating disorders. In my recovery journey, it’s been more difficult because I’ve felt more alone. As I got older, I started to understand that even though [eating disorders] may be disproportionately affecting one gender more than the other, we’re still in the same battle.

Not only was it difficult for Woelbern to connect with others, he also struggled to break away from gender stereotypes and open up about his eating disorders

“For me, it’s definitely difficult [to talk about my eating disorder] because you feel like you’re jeopardizing your manliness in a sense,” Woelbern said. “It makes you feel like less of a man deep down inside because that’s what we’ve always been taught: that your emotions shouldn’t boil up and you shouldn’t feel a certain way about some things. But it still hurts and when [your emotions] do start to boil up, you don’t really want to talk to anyone so it just keeps feeding itself.”

Rhee said that the brains of people with an eating disorder actually function differently than someone without, causing their adverse reactions to food.

“Typically when you eat, there are certain parts of your brain that light up in imaging studies because your brain is happy,” Rhee said. “In a patient with an eating disorder, that part of their brain actually doesn’t light up. It’s not happy that you ate.”

Because eating disorders rewire brains to think differently about food, Rhee said that it’s important for her to be strict with treatment plans for her patients in order to show them that they have agency over their eating patterns.

“You have to really be strong around the protocols and the rigidity of what we’re doing to show the eating disorders that they are not in control of this person’s brain anymore,” Rhee said. “[My team and I are] going to take control, we’re going to set the rules, we’re going to get them to eat again. It is sort of resetting the body. We need to try to teach their eating disorder and the kid that you’ll be okay if you eat all of these varieties of foods. In the grand scheme of things, it’s not unhealthy.”

In an effort to help others going through the same thing she went through, Litchev started the Body Image Task Force club at Westview.

“It was a new club that I formed online last year, especially because I felt [that] during COVID, a lot of eating disorders and disordered-eating patterns spiked because of the isolation,” Litchev said.

As president of the club, she posts on Instagram, finds body-positive influencer guest speakers, such as dieticians, and discusses how to change the language surrounding body image. She also discusses ways to combat diet culture, like rejecting general beliefs. .

“I help educate our club and lead the sessions about diet culture, fatphobia, and disordered eating,” Litchev said. “I also offer healthy coping mechanisms to combat societal pressures about food and exercise.”

Because high-schoolers are constantly bombarded with misconceptions from the media surrounding dieting and body image, Litchev said that she hoped to educate students in her club about the truth.

“The whole goal is to bring awareness to important issues surrounding body image,” Litchev said. “In a society that promotes unrealistic body ideals, people often find themselves making unhealthy comparisons and I hope by educating and combating diet culture we’re able to inspire a neutral or more positive view of our bodies.”

Litchev said she wants to educate students, strengthen their relationship with food, and improve the way they speak about eating.

“It’s important to educate ourselves on how to debunk diet culture ideals and work towards developing a healthier relationship with food and our bodies,” Litchev said. “I think reframing our language around food and exercise would also be helpful. For example, stop talking about diets and commenting on people’s bodies.”

Rhee said she believes that portraying diverse beauty and people of all body sizes in ad campaigns is one of the most potentially powerful tools that would help increase body positivity and destigmatize certain body shapes.

“I think [we need to be] putting that message out there that everybody is beautiful in their own way and that inner beauty and personality make a person lovely,” Rhee said. “But that’s hard to portray in a flat image in a magazine. We need to stop just picking one type of body height and weight and idea of what beauty is and start representing what people actually look like.”

Litchev said she also thinks it would be beneficial if more companies, especially clothing brands, worked on combating body image norms, as this is what most influenced her.

“As consumers, we can help make changes by [supporting companies when they] expand their sizing options or [diversifying] the models portrayed on clothing websites,” Litchev said. “Also, not following fad diets and buying weight loss pills because the diet industry gains so much profit from these buys.”

The fashion industry and other forms of media that influenced Litchev’s eating disorder impacted not only her physical health but also changed her life drastically in other ways.

“When you’re preoccupied with your eating disorder, it really ruins your life,” Litchev said. “It impacts all your goals and ambitions, and things you used to love you don’t enjoy as much.”

Litchev said that her harmful relationship with food also ruined some of her relationships with the people around her and made it difficult for her to get accustomed to a new school.

“My eating disorder definitely made me isolate myself,” Litchev said. “I never got the opportunity to make friends because I was so hyper-focused on food and exercise. When you don’t fuel your body enough with the proper nutrients, it makes you really irritable, so I didn’t have a good relationship with my parents because I treated them badly.”

For Woelbern, it was difficult to manage the mental toll of focusing on his eating disorder while maintaining social connections. While at the height of his eating disorder, Woelbern said that he cut out most of his friends.

“Cutting all those people off definitely affected my people skills and how I interact with people,” Woelbern said. “When I was in the clinic, my schoolwork was definitely lower because I wasn’t able to have a lot of time to do it. You focus so much mental energy on thinking about food and thinking about what you’re eating that you feel drained.”

Litchev worked with a therapist and dietitian to help treat her eating disorder. Now, two years into recovery, she said that she has a greater appreciation for food and a better relationship with her own body.

“I eat when I want to, how much my body wants to, and towards satisfaction,” Litchev said. “I exercise for my mind and not for my body. Food is not only fuel, but it’s a part of your life. Food is culture, food is a way to socialize. We forget that even if you’re not hungry, you can have a cupcake just because it’s your birthday.”

For Woelbern, it was constant reality checks that helped him overcome his eating disorder.

It’s been a long, arduous journey,” Woelbern said. “It was a lot of reality-checking myself after being exhausted by what I’ve done. It’d be months of restricting and bad eating habits, and then, one day, I’d wake up and think, ‘This is not what I intended, this isn’t going to help me with water polo, this is taking up too much of my life.’ These reality checks caused me to start looking forward, getting into more hobbies, and having less time to ruminate.”

Woelbern said that participating in sports also impacted his non-linear recovery as it was hard to balance his sports-related goals and his recovery goals.

“Once I started doing water polo, it became a dance between wanting to get better at my sport and looking the way I wanted to look,” Woelbern said. “I wanted to get better, I wanted to have enough energy to play well, but that counteracted with how I wanted to feel.”

By educating herself on the facade of diet culture, Litchev is now able to push away negative thoughts about body image, even though diet culture is impossible to avoid.

“I think that there are moments when the thoughts come up, but I’m at a point where I’m able to continue doing the things I’ve been doing even with the thoughts that resurface,” Litchev said. “That’s what recovery’s all about.”

Eating Disorder Hotline:

(800) – 931 – 2237