A Future in Flux

Despite anxiety about its potent capabilities, students and alumni tentatively embrace A.I.

The AP Government study guide was a pain. Will* knew that from first glance nearly three weeks earlier when it was assigned.

“I viewed it as time-consuming,” Will said. “And time-consuming in a way that didn’t necessarily improve learning, because it was all information that I had reviewed before. I just needed to collect it and put it all together.”

Two days before it was supposed to be finished, the pages were still blank. Sitting there, staring at it, he decided to try something he’d done only a few times before—he plugged the questions into ChatGPT.

Answer the following in full sentences and include a summarized main idea for each section, he typed, before pasting in the guidelines his teacher had provided the class with. ChatGPT didn’t rain. It poured. In less than fifteen seconds, an entire assignment was completed, ready to be pasted into a Google Document and reviewed at leisure.

For Will, this isn’t a common occurrence. He doesn’t use ChatGPT on every homework assignment he has. When he does use it, he’s come to accept that there are certain limits on what he can and can’t accomplish with the help of A.I. So far, the tentative limits he’s tested—and gotten away with—include what he views as busywork mostly in the vein of defining terms or answering basic questions.

“If I subtract the hours I’ve spent just fiddling with prompts to make it tell me stupid stories and write poems that rhyme my friends’ names with animals, I think it’s been most useful for saving time,” he said. “If I don’t feel like putting in legwork, ChatGPT can do it for me.”

He had first stumbled upon the tool after reading a New York Times article about it earlier this year. Immediately afterward, he had signed up for an account. The prospect of a tool that could synthesize the whole of the internet for him into a human answer was appealing, he said.

“If nothing else, the novelty was cool,” he said. “I remember pulling it up on my computer with my friends just to see what it could do, and to see if the warnings about it taking my job one day felt true.”

Initially, he wasn’t impressed. While the interface was sleek, he couldn’t get it to output a full, thought-out creative piece that would be of actual quality, or anything that displayed human ingenuity.

“It breaks ground in that it acts like a human, but it wasn’t enough to pass off as human except to the laziest eye,” Will said.

As he got used to the various limitations of the tool and understood more clearly how to use it however, there was an almost immediate sharpening of anxiety, one that more and more people have felt as A.I. tools have entered the mainstream.

“I think what really made me worry was the fact that I can’t really get it to give me sources,” Will said. “I have no idea what and how its algorithm is making my input, or really where any of the information is coming from. It’s kind of a pain if my assignment asks for sources, and what I’m getting are dead links that ChatGPT made up.”

This lack of transparency poses a problem to more than just student homework accuracy. While Will may take issue with the fact that his answers can’t be cited in a bibliography, the ramifications of information that appear credible but are unbacked are of far greater consequence. Psychologist Austin Brooks, who has conducted research on ChatGPT and has a book forthcoming on the consequences of the new tool, has found that there is a concerning lack of transparency.

“It’s literally a ‘black box’ problem,” Brooks said. “Not in the sense that ChatGPT is actually sentient and thinking for itself, because it’s not. But more in the sense that a dilemma exists when an AI decision-maker has arrived at its decision in a way that is not currently understandable.”

This doesn’t mean that A.I. is becoming human. To Brooks, incidents that have sparked public concern about A.I. evolving sentience are only reflections of our greatest fears of what this tool might become.

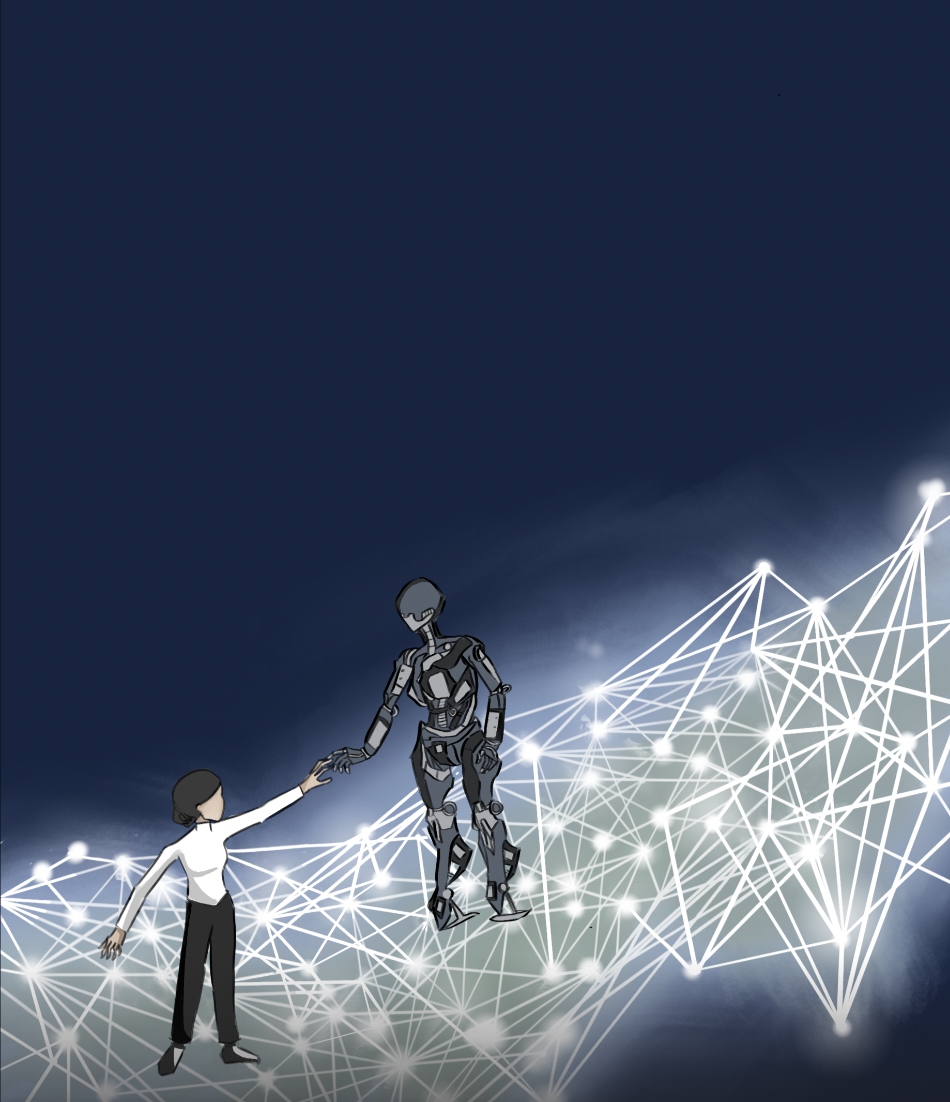

“The problem lies not in what ChatGPT can do, but in what we can do with it,” Brooks said. “At one point, A.I. will be able to accomplish nearly everything a human can—when it comes to the film industry, for example, it will be able to write scripts and edit them and generate art to animate said scripts. At that point, and even now, it’s about our responsible usage of the tools we’re given.”

Despite this, across the world, A.I. has made its way into the mainstream. In the past year, Google, Microsoft, and Apple have invested tens of billions of dollars total in A.I. research. As their investments have come to fruition, almost suddenly, A.I. is everywhere.

As a freshman at the University of Southern California, YJ Si (’22) has seen new innovation on the heels of the popularization of the tool.

“Since it feels like ChatGPT was really suddenly sprung into use mid-term, I think a lot of professors were really unprepared for it,” Si said. “But as it’s become more popular, I know of classes where it’s being incorporated into the curriculum, and where students are being asked to use it in creative ways.”

This includes seminars on artificial intelligence sentience and speakers who’ve delved into the field, as well as their concerns about the eventual economic impact of emerging tools. As a journalism major Si has heard more than his fair share of prophesying about the extinction of the jobs he’s long aspired to have.

“I recently attended a workshop on how A.I. is going to change the landscape of media,” Si said. “The biggest message was basically ‘adapt or be overcome’ in the sense that we need to get with the times and the tools that are being offered, or be left behind.”

Adapting, however, has come with its own set of growing pains. Given how fresh the technology is, the possible consequences of it are as of yet unknown.

“What we don’t know can and will hurt us,” Brooks said. “In our current political and social landscape, some of our biggest problems are already misinformation and division. ChatGPT is an insane tool in the wrong hands—there are bad actors out there who can and will exploit the capabilities of a machine that can produce information that seems real and plausible and written by a human, at a rate that no human can ever achieve.”

In the workforce ChatGPT has likewise been both a tool and a source of anxiety, particularly for those working in creative fields.

After journalist Matt Stevens (’07) first heard of ChatGPT in an article published by the very newspaper he worked for, his immediate reaction was tinged less by shock and more with acceptance. He understood, he said, that it was just another possible obstacle facing workers in an industry already periled by public mistrust and lowered ad revenue.

“As long as I have worked in journalism, the threat of layoffs because of diminishing ad revenue and other issues has been omnipresent,” Stevens said. “I’ve gone through several rounds of buyouts, leadership changes, and company changes. Even at The New York Times, I can say we’re back in this period where we’re a little bit on edge. While A.I. is something that is going to get better faster and potentially become a threat to consider, I guess I just feel like it adds to the mix of threats that journalists feel all the time.”

Still, he believes in the future of the work that they’re trying to accomplish, he said.

“The type of journalism we’re trying to do at The Times, tends to not be the kind of writing reproducible by A.I,” Stevens said. “The stories we work on involve analysis and really good reporting and source management and talking to people and searching for the right court documents, and all of those things are what A.I. can’t do yet. ”

This hope—that the originality of human effort and spirit will remain unique—is one that Sam Bozoukov (’15) likewise harbors, as he’s completed studies as a part of his Renaissance Literature PhD candidacy at Harvard University.

He’s seen firsthand a tentative embrace of the tool. For the student work he reviews, there’s been new guidelines put in place.

“At least this semester, [at Harvard] how we’ve dealt with it is that professors are being very explicit about students being transparent,” Bozoukov said. “Students can use it, but they need to explicitly show what was written by ChatGPT and what you change yourself.”

While no students have announced their use of the tool this semester, or turned in noticeably artificial work, Bozoukov has seen burgeoning exploration of this new avenue.

“It was interesting because last semester, one student—a computer science guy—had some parts where he footnoted that he had asked ChatGPT to write in the style of Virginia Woolf,” Bozoukov said. “And if he hadn’t told me I would’ve thought nothing of those sentences.”

Alternatingly, ChatGPT has also become a source of inspiration.

“I use it as a calculator or a compass in the sense that I let it point me in the right direction to go,” Bozoukov said.

He’s been able to use it as a jumping-off point for introductions to research papers and a way to learn how to better refine his grant application cover letters for Bozoukov himself.

Amidst all this, Bouzokov, like Stevens, acknowledges the possible dangers ChatGPT poses towards a career working in literature, something that has always felt precarious when it comes to long term financial viability. Though ChatGPT may be uniquely useful to his field, Bozoukov has never forgotten that what he’s holding is a two-ended weapon, one that may one day hurt him as much as it has helped.

“I’ve definitely questioned myself more [with the advent of A.I.-driven writing],” Bouzokov said. “Since I have a wife and a daughter to support, it’s become harder to justify pursuing a passion of mine, when I’ve had to really think about the possibilities for employment, now more than ever.”

More so than other fields, English, and writing-focused humanities in general, is one that has long been predicated on a fight of relevancy and survival in the 21st century. According to the New Yorker, during the past decade, the study of English and history at the collegiate level has fallen by a full third. ChatGPT is just another blow to the job security available to those who choose to study it.

“There are going to be entire industries that are permanently altered by the advent of A.I.,” Brooks said. “As the speed of innovation accelerates, we’re going to see more and more changes to our traditional ideas of employment, because American capitalism means everything is focused on the bottom line, and A.I. can mean huge gains, economically, because it will one day be more easy to manage than a person.”

Still, Bozoukov said he believes that writing itself will persist beyond the machinations of algorithms. To him, a lot of the times what makes good human art appealing is the mistakes and imperfection and very unique phrasing that ChatGPT cannot generate. No matter how good algorithms get at imitation, what they’re imitating is still what humans have written, he says.

“At the end of the day, art, especially writing, is a two-person job, between author and audience, forever a dialogue,” Bozoukov said. “The two become who they are through the other; the author depends on us to recognize them in and through their work, as we depend on the artist to reveal us to ourselves. AI-art (even pictorial art, I’m realizing now) is a ghost, a shadow of a shadow, for now; and if we recognize ourselves in its work, then it’s perhaps more a reflection of who we are than what it is.”

Will has continued to use ChatGPT, despite his increasing anxiety about what the tool might mean in the future. He’s begun to accept it to some degree, as a next step. After all, he says, like his peers, he can’t remember a time when he didn’t have the internet at his fingertips, just like someday, there will be students who can’t remember a time when they didn’t have tools like ChatGPT at their disposal.

“We can’t take it back now, so we have to keep moving forward in unison, in collective,” Brooks said. “This is a bigger issue than it seems right now, because so many of us have no idea of what’s happened [now that something like this] is available.”

Fundamentally, things feel like they have shifted, Will says. No matter where ChatGPT and its shifting algorithms of language take us, education—and other institutions—will be forever changed.