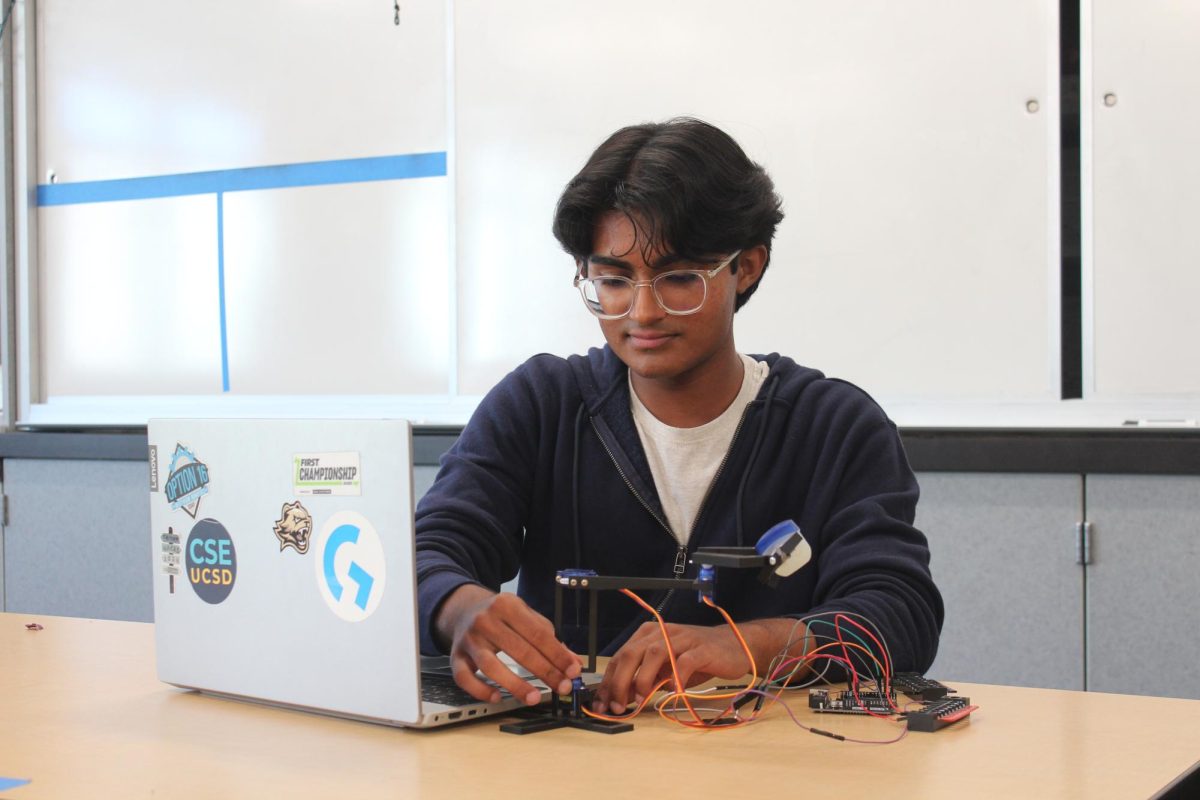

Armin Kamsi’s (11) video game, Gun and Dun, was horrible. Plain horrible, accord

ing to a video game critic who left a review of it on STEAM, the gaming platform where 14-year-old Kamsi had uploaded it. “Lackluster implementation” and “extremely low visual quality” made for a “slapped together” experience, the review read.

“I needed that,” Kamsi said. “I needed that because I was on a high horse. I was like, ‘Oh, I made a game on STEAM at 14, look at me go.’ But that was the problem. That was the only goal bec

ause I wanted to have a game on STEAM.”

In 2022, Kamsi reevaluated his goals in video game creation. He wanted to tell a story, a good one, in a way that invited direct engagement. After playing a survival game called ARK, the inspiration for Foragery was born.

“In ARK, you’re on an island, and you have to face dinosaurs,” Kamsi said. “I thought, ‘Maybe I should make a game similar to that, where you have to fight off animals.’ But then I thought ‘I don’t want to hurt animals, that’s not really good. Why don’t I make it more peaceful, where you don’t have to fight any animals, and instead you have to just get off the island?’”

Foragery is just that. Stranded on an island, without any memories of how they wound up there, players have to make their way around unfamiliar territory, building a life for themselves while simultaneously collecting the materials they need to make a boat and escape. Along the way, they venture out on sidequests, learning more about their space and themselves.

To fit with his slow-paced, nature-centric themes, Kamsi drew heavily upon the iconic video game Stardew Valley for his atmospheric designs.

“I love the details [like] the way that the rain falls down,” Kamsi said. “It’s a survival game, but it can still look nice and be visually relaxing. I love nature.”

Every good visual must be accompanied by music, so Kamsi downloaded the app G

arage Band and began experimenting with tunes and melodies for various scenes within his game.

“I started looking at music theory and stuff like that,” he said. “[I had prior experience from] when my friend and I almost started a band. I started making beats and lyrics in that era, so I got used to that kind of work. For Foragery, I just kept trying over and over, trial and error, until I got there.”

With aesthetics mostly decided upon and drawn up, Kamsi moved to tackle the bulk of the labor necessary for making a video game: programming. In order to avoid a repeat of his previous games, which came across as rough and simple, he was more ambitious with his technical design. Opting for top-down graphics, which are 2D but give the illusion of 3D, was a time-consuming creative decision for Kamsi.

“[Top down] takes a long time, especially because you have to make it go up, down, left, and right,” he said. “It can get really draining because you’re just seeing the same image over and over, you’re just putting new colors on it. ou’re changing its animation, but it’s still almost the same as pictured a million times, and then you start thinking it looks bad because your eyes are getting used to i

t. So that’s also very challenging. I think persistence is key when making a game worth playing.”

Being the single producer of Foragery means that Kamsi has to find the time in his schedule to perfect every single aspect of the game without assistance.

Although plotting, programming, and visual design are enjoyable parts of his gaming journey, there’s one unavoidable aspect of creating a video game that Kamsi is less fond of: bugs.

“A bug is when you’re trying to run your code, and it simply doesn’t work,” he said. “Especially making games, your game will crash, and not work through your engines. An engine is where you put your code and assets, and it will tell you what happened. But it doesn’t tell you in basic English, it tells you like this: ‘blah, blah, doesn’t work execution, blah blah blah,’, a bunch of technical stuff, an

d you have to know what it means.”

Thankfully, his extensive research of the coding languages and platforms he uses has taught Kamsi to troubleshoot and debug his work with generally minimal difficulty. His secret? The internet.

“YouTube was the main way I started because there was no computer science class in elementary school,” Kamsi said. “I did do some summer camps, maybe nine in my life. But I was already so advanced at home, that even more advanced camps would be kind of a waste of tim

e for me. I think I could have learned more on YouTube. So that’s how I learn coding. It’s all basically on the internet. ”

Now that Foragery’s demo has been released, Kamsi has turned his attention to finishing the game, something he hopes to accomplish sometime around the beginning of the next schoo

l year. From then on, Kamsi hopes to relish in the completion of his project, enjoy senior year, and look forward to a lifelong future in programming and game design.

“I plan to work independently as a developer,” he said. “Hopefully, I’ll get a Master’s, get something going for game design specifically, and make games until I retire. Until then, I’m happy to just work on finishing this game and getting it out there.”

Armin Kamsi • Mar 15, 2024 at 6:10 pm

Thank you guys! Cora was a great interviewer and asked the best questions!