Ethnic Studies students make ecobricks, clean campus

January 27, 2023

As lunch came to an end and 20 minutes of SSH began, Aadya Nayak (12), Marissa Kanoya (11), and the rest of their project group went around campus amassing an abundance of plastic trash, discarded in trash cans or on the ground by students.

“During SSH we would go outside on campus and see if there was any [plastic] trash on the ground [or on] top of the trash cans,” Nayak said. “We [would sit] at the lunch tables and sort through all the trash to catalog on a Google spreadsheet that says how many chip bags or straw wrappers we found.”

For the last unit of their Ethnic Studies class, focusing on activism, Kanoya discovered the process of “ecobricking” and shared the idea with Nayak and her peers. Created by Benish Desai, a young entrepreneur, ecobricking helps accumulate trash that is littered around a community and is then repurposed to build homes, fences, furniture, and children’s playgrounds.

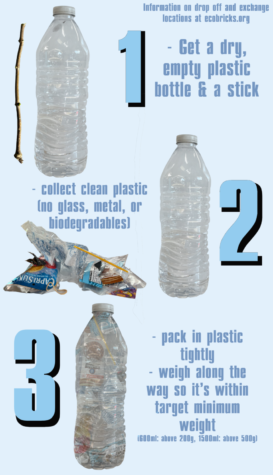

“[You take] a plastic water bottle that is empty and stuff it full of trash and [then] it becomes heavy and sturdy,” Nayak said. “Plastic doesn’t degrade easily, so it creates housing structures that are sustainable for several hundreds of years.”

Through the organization Global Ecobrick Alliance and their drop-off centers, these trash-stuffed water bottles can find their way from Nayak and Kanoya’s Ethnic Studies class all the way to assisting the construction of buildings around the world.

“[The organization] tries to go to places where there are housing crises, [especially] in low-income and housing-insecure countries,” Kanoya said.

Ecobricks are mostly being used throughout the UK, the Philippines, Guatemala, and South Africa, but Kanoya said people will even use them to construct things for their own home.

“A lot of people have been making their own planter boxes,” she said. “You do not have to give back to the organization. At the end of the day it is just repurposing your plastic somewhere around your house or community”

Despite its seemingly easy process, Nayak said ecobricking takes more than just acquiring a stockpile of trash until the bottle is full.

“It can take a bit of time, especially if you do not find the plastics that fit,” she said. “You also have to weigh it so it’s not just [stuffing] until you feel like you are done; there is actually a certain weight requirement.”

Nayak said she recommends ecobricking to anyone who is looking for a way to assist the mitigation of plastic waste in their community in an easy, accessible way.

“All the necessary materials are right inside your home or really close to you, and it’s not a very time-consuming project either,” she said.

Kanoya said the experience of collecting trash and making ecobricks has opened her eyes to the amount of trash on campus, with one bottle containing more than 250 pieces of plastic. Nayak said the impact of seeing the plastic affected her own awareness of her consumption habits.

“Especially since it’s clear, it offers a really good window into how much plastic you are consuming and it’s a really powerful visual of that,” she said.

Although ecobricks are far from being a permanent solution to the global problem of plastic pollution, Nayak said its impact is still great, starting from individuals who want to take initiative.

“It makes me realize how other people would also be affected by ecobricks, [and] that iss what motivates me to keep doing it,” she said. “By being able to talk about it with our [peers], hopefully we will be looking forward to making a more sustainable future.”