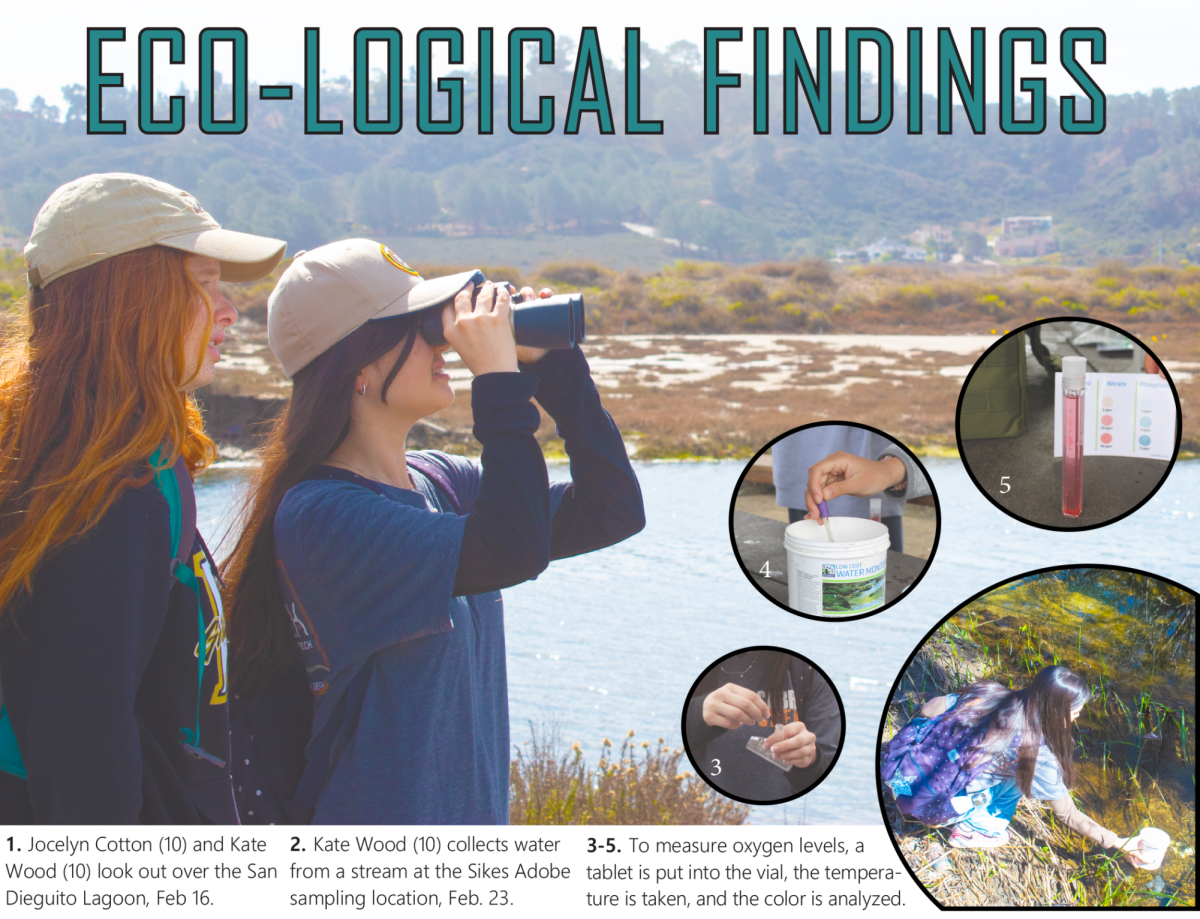

Kate Wood (10) clambered down into the reeds and muck that made up the bank of a small San Dieguito River offshoot, Feb. 16. Trying her best not to slip, Wood bent down to collect a water sample from the stream in a small bucket. The Conservation and Environmental Stewardship Apprentice program (CESAP), which includes five Westview students, has been collecting water samples like these from six different sites along the San Dieguito watershed in order to publish a scientific paper on the health of the ecosystem.

Students like Elizabeth Weng (10) ran tests on the water to measure the levels of four different water quality indicators: phosphates, nitrates, PH levels, dissolved oxygen, and fecal bacteria.

“We each are in charge of measuring different levels of nitrate, oxygen levels, and more by measuring out water from the buckets and inserting a tablet,” Weng said. “Once the tablet is dissolved, the water could have a number of different pigments that each tell us something different about the water quality. We do this to eventually compare it to water samples we got from the other areas as well.”

The water quality of this watershed hasn’t been studied in a decade, which is why the Ecologik Institute — a nonprofit dedicated to empowering young women in STEM and the parent organization of CESAP — has Wood and Weng, along with Maya Spinney (10), Jocelyn Cotton (10), and Chloe Lestyk (10), collecting these water samples.

As part of the program’s research cohort, the students work with CESAP staff to prepare and present data to the park’s rangers, biologists, and shareholders on the health of the watershed.

“With this information we’re trying to show park rangers and scientists how water changes through the watershed, and so they can see [if] their treatment plans work, or to just see how they could better the watershed,” Wood said.

Currently, water samples have been collected from five sites, and the presentation of the cohort’s data is scheduled for May.

To prepare for the presentation, Ecologik program manager, CESAP instructor, and wildlife biologist Brooke Wilder taught the students how to decode scientific papers. She gave them various studies and guided them in interpreting the sometimes-confusing academic jargon and structure. Weng said she appreciated this teaching.

“When you think of a scientist you think of someone who works in a lab or who does experiments all day but they’re definitely more than that,” Weng said. “I think one thing that a lot of people don’t think about is that even after you make a discovery in science you have to share it or spread it somehow and [our CESAPP mentors] are definitely very good at science communication and also just communicating ideas to high schoolers that may not have as much experience in the field.”

The field work the cohort does is very hands-on according to Wood.

“We do a lot of place-based learning at [CESAP] and [I like] the idea that we’re not learning about what we’re going to do in a classroom, we’re learning about it by doing it,” Wood said. “It’s a lot easier to make observations more engaging.”

The cohort started sampling at the beginning of the watershed, near Iron Springs on Vulcan mountain. Wood said that the wildlife impressed her, towering trees that she said looked similar to sequoias lined the paths they took.

“We were just in the middle of nowhere collecting water from this tiny little stream that came right from the springs,” Wood said. “One really interesting thing that we found is that there actually was almost no dissolved oxygen in the water. Dissolved oxygen is really important [for aquatic life]. You’d think that spring water is quote-unquote perfect, right? But since it’s right out of the mountain, there’s no plants to bring oxygen inside.”

During and after the treks to the collection sites, the students are led around by local rangers, and taught about local flora, fauna, and environmental issues.

Spinney said her favorite site was Sike’s Adobe, the second stop on the watershed, because of the interesting things she learned from Park Ranger Calie.

“Our mentors pointed out invasive plant species like the common mullein, which they explained that cowboys and traveling men would rub on their skin to smell better, acting as sort of a cologne,” she said. “We then all took turns rubbing it on our arms!”

Having mostly female role models was important to Wilder: someone who advocates strongly for supporting women in STEM.

“I was somebody who almost didn’t go into science,” Wilder said. “I had really struggled with math when I was in high school, and I thought that meant I could never be a biologist. But it turns out that I just needed the right environment and the right kind of guidance to be able to learn those skills. I found that in community college when I had a much smaller class size and much more one-on-one time with a professor, I didn’t get left behind. And I didn’t want that to happen to any other young girl.”

Wilder said that getting young women into nature, and teaching them the scientific skills needed for field and lab work is an incredibly important part of the program.

“There’s research that shows that young girls often struggle with math confidence,” Wilder said. “They struggle with being able to see themselves in the role of a scientist. And luckily that’s changing, but I wanted to be part of that solution.”

Spinney said that this program was what got her interested in the STEM field, having focused mainly on humanities in the past.

“Science was just something that I didn’t find as interesting as reading and writing for example, so my head never turned that way until I heard my friends were involved in this CESAP program,” Spinney said. “I did feel discouraged at first because the STEM fields seemed pretty intimidating, being that it combines math and science, two subjects I was not very familiar with in terms of what my passions are. Now I not only find myself more knowledgeable about our environment, but eager to learn more and eager to ask more questions.”

![Jolie Baylon (12), Stella Phelan (12), Danica Reed (11), and Julianne Diaz (11) [left to right] stunt with clinic participants at halftime, Sept. 5. Sixty elementary- and middle-schoolers performed.](https://wvnexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_1948-800x1200.png)