Academic Honesty Policy fails to deter cheating

According to a 2015 survey conducted by the International Center for Academic Honesty, 95% of students surveyed admitted to some form of academic cheating. Cheating is a widespread issue that has only become worse with distance learning, as teachers have trouble catching students.

Students cheat for all kinds of reasons, including performance anxiety and academic pressure. Especially at Westview, where students are encouraged to take high level classes, students face pressure to perform. This pressure is reflected in the classes Westview students take, with U.S. News reporting that 71% of students at Westview took an AP class during the 2019-2020 school year.

There is no doubt that these advanced courses are designed to challenge students and build their understanding of the subject at hand, but students can find themselves in over their head and forced to turn to cheating as an alternative.

“I took 3 AP classes this year because I wanted to boost my GPA,” Suzie* (11) said. “I’m constantly stressed about academics and I don’t have much time to study; I have to juggle 2 sports, an internship, and school. I resorted to cheating because it was the easiest way for me to maintain my grades without putting too much mental strain on me.”

And academic pressure is not exclusive to these high level courses, as students taking standard Westview classes still face the pressure to perform at a high level.

“I feel pressured to do well in school and get good grades whether I’m in an AP class or not,” Tommy* (11) said. “I’m taking extra math classes that aren’t required for graduation so that my schedule looks better even though it isn’t an AP. The pressure mainly comes from my parents.”

There are many different ways to cheat, and therefore many different types. Students plagiarize and copy in English and history, use Photomath and their phones in math, and ask for help from higher level speakers or use translators in foreign language. Cheating occurs in nearly every class, and has become even easier to do during distance learning.

Westview has a policy, dictating what is considered cheating and the consequences for students who violate the rules, using a first, second, and third offense system. The consequences become more severe with each of the three tiers, but all three contain the core punishments: a zero on the assignment, a referral, and contact home.

Teachers are usually the ones handling cases of academic honesty and enforcing this policy as they are at the forefront of catching academic cheating. Referrals are usually given when teachers catch more severe instances of cheating, or find that students are habitually cheating. In these instances, the case will go to an area administrator.

“When the case comes to us [area administrators], it is because an incident of cheating has escalated and the teacher has issued a referral to a student,” Area Administrator Teri Heard said. “The policy allows us to be flexible and treat each case differently.”

The Westview academic honesty policy only deals with cheating in general. Departments often create a more specific policy that is tailored to their subjects. Punishments for academic dishonesty typically differ from teacher to teacher and department to department.

“My department has our own policy to deal with academic honesty,” math teacher Matthew Ingham said. “We found that it’s more strict and takes more time to enforce, but it is effective at deterring and punishing cheating.”

The math department’s policy lays out what constitutes cheating, and violators receive a zero on the assignment, a referral, an email or phone call home, and students must write a statement about what happened. And as teachers differ on how they implement their policy on cheating, the math department’s approach is very different than how Spanish teacher Silvi Martin approaches the topic of cheating.

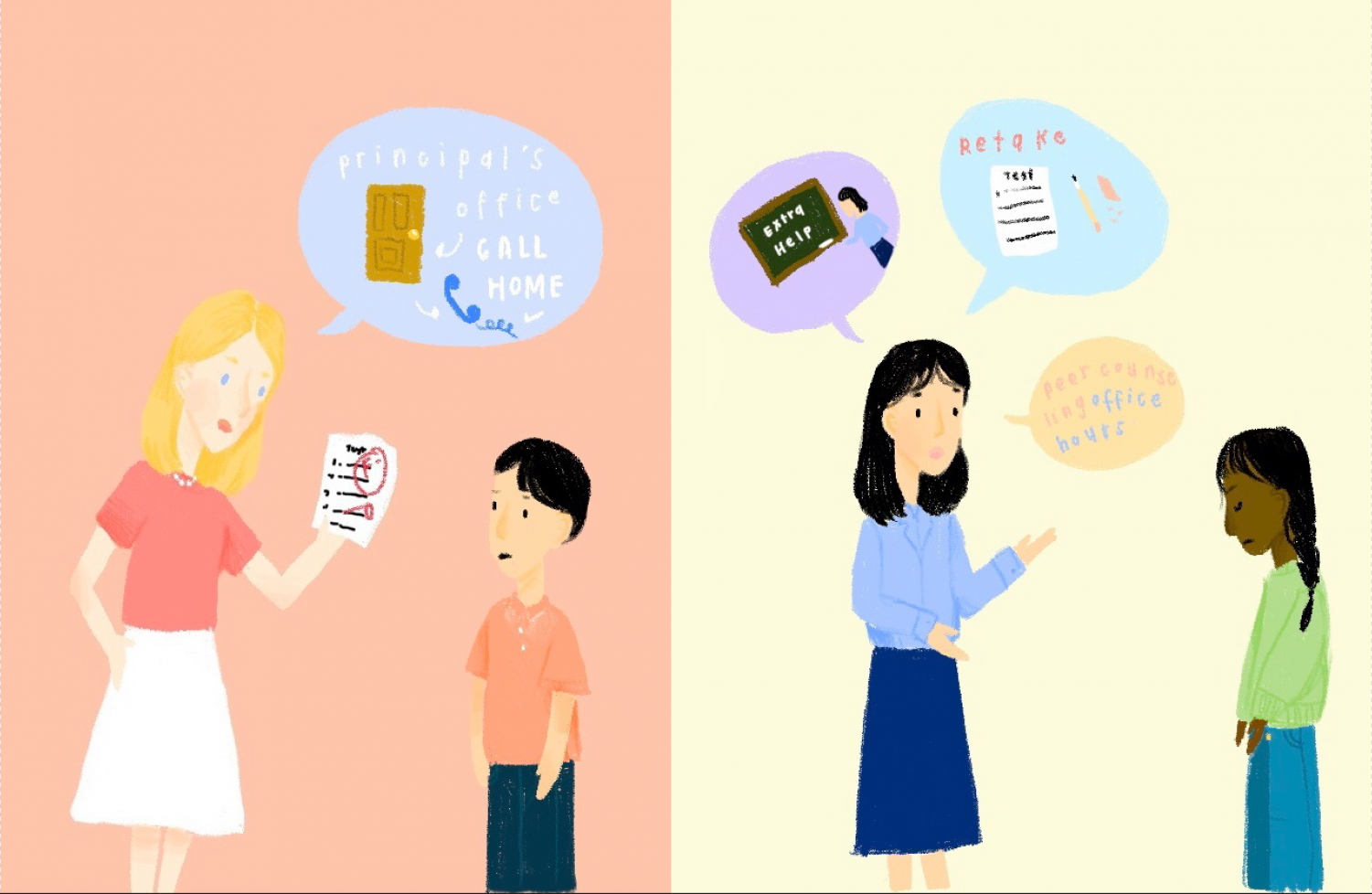

“I find that students cheat in my class because they are not confident in their abilities,” Martin said. “I try to connect students with learning, and help them as much as I can so they don’t need to cheat. And if I do catch somebody cheating, I give them a second chance to prove they know the language.”

Though Martin believes in a second chance for students, other teachers, like math teacher Katherine Bell, believe that students should swiftly face consequences for cheating.

“If a student cheats in my class, it’s a zero, an immediate call home, a student-teacher conference, and sometimes a referral,” Bell said. “I think cheating comes from desperation, and I would rather students be desperate now and face the consequences now, rather than later on when consequences will be far harsher.”

The consequences are very different in college than in high school. Whereas at Westview, cheaters will face a zero, a call home, and a referral, cheating at the college level can result in the failure of a class, fines, revocation of scholarships, and even expulsion.

The stakes are certainly raised at higher level education, which is why teachers must also find effective ways to prevent cheating in high school, discouraging cheating in the future. These methods of prevention are often found in the academic honesty policies of each department.

“The math teachers all generally use the same techniques,” Ingham said. “We create questions and different test versions, we use paper divides to separate students, and we try to ensure that students don’t have access to their cell phones. Online is much harder, but we can still use different test versions, and PhotoMath’s advanced methods of solving problems are very easy to spot.”

Other teachers, like Martin, employ tactics specific to their class’ needs to discourage cheating in the classroom.

“I try to remove students’ need to cheat by providing availability to help,” Martin said. “I find that students cheat less as the term progresses, as they’ve asked for help and become confident in their abilities.”

Science teacher Mike Kurth uses a combination of the two methods to create an environment that dissuades students from cheating.

“I scramble the multiple choice and I use different free response questions for each period,” Kurth said. “I give questions that force kids to think. I allow them to use their notes, so I can encourage them to take good notes, and be able to apply what they’ve learned to the questions on the test. I also try to be open for questions, because I want to help students learn and understand what they’re learning.”

The school policy is very general and generic, not especially focusing on clarifying the subject of academic honesty in order to allow teachers to interpret and implement the policy as they see fit. However, the policy also focuses on immediately punishing students, an idea Kurth thinks could be improved.

“We create an environment of entrapment, both for teachers and students,” Kurth said. “Students are expected to perform in a high-pressure environment, and teachers are expected to punish students, while also trying to reduce that pressure. Expecting teachers to issue a referral whenever a kid cheats isn’t fair, both to the pressured kids and the busy teachers.”

*Students’ names have been changed.

For more information, refer to the other two parts of our cheating series.