Being Nonbinary: The Impact of Pronouns and Gender Identity

Using proper pronouns creates an inclusive classroom environment and improves students’ quality of life.

For a long time, Mars Whiteside (12) said their gender identity felt like a jigsaw puzzle with pieces that didn’t quite fit together. According to Whiteside, they had the wrong hair, wrong voice, wrong face, wrong hips, wrong body.

The wrongness Whiteside is describing is dysphoria, the distress someone who does not identify with their assigned gender at birth feels about that assigned gender or with their body.

Whiteside is nonbinary, meaning they don’t identify as either a male or a female. Whiteside said that because of the assumptions people automatically make about gender, it can feel invalidating and painful. They described it as existing in a world that wasn’t built for them.

“The thing about being nonbinary, in particular, is that if a stranger comes up to you, they’re going to get it wrong 100% of the time, or at least 99% of the time, because it’s not something that people assume yet,” they said. “When you walk up to someone, you stick them in a category and it’s man or woman, and then I’m screwed because they’re never going to get it right and both are wrong.”

Being Misgendered

For Isa Planken (11), another nonbinary student, using their right name and pronouns is essential them being able to learn and be productive in class.

“When you’re in a positive environment where people call you what you want and respect you, it’s easier to actually learn and participate in class,” Planken said. “In a school environment, when people don’t call you your name or what you want to be called, it’s like everything stops and you hyperfocus on that and it’s even harder to learn when that happens.”

This experience of being called by the wrong name is often referred to as being deadnamed, while being referred to by the wrong pronouns is being misgendered.

Whiteside described being misgendered as feeling physically gross, a sensation they said that at its core is a feeling of wrongness.

“If someone knows, and they mess up, it feels like they’re saying that they don’t care about you,” they said. “If someone does it because they don’t know, then there’s this anxiety about having to correct them and not knowing how they will respond.”

Planken described being deadnamed and misgendered as invalidating, making them feel like a joke.

“If you refuse to call me the name that I want, it just makes me question my worth as a person,” Planken said. “If you’re going to go out of your way just to do something that I don’t want you to do, it makes me question, ‘am I even worth it?’”

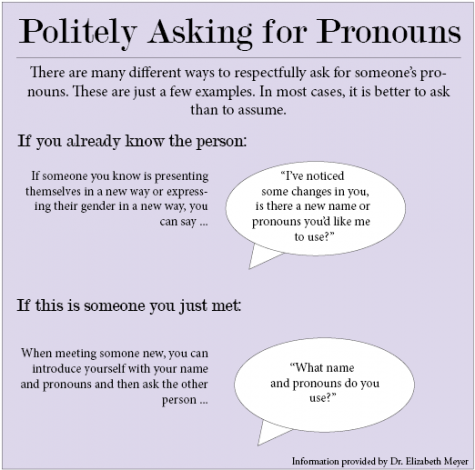

According to Dr. Elizabeth Meyer, professor of educational foundations, policy, and practice at the University of Colorado, Boulder, this experience of being deadnamed or misgendered is painful, alienating and can cause lasting damage to the person’s mental health.

“Having somebody address you in a way that is not consistent with how you identify is a consistent source of pain and harassment if you’ve actually told the people that’s not how you identify,” she said. “If somebody continues to misgender you or misreference to you after you’ve told them ‘I don’t identify that way, I use this pronoun,’ it can be construed as harassment because of the long-term psychological harms [being misgendered] causes.”

Sharing Pronouns

Because Whiteside uses a different name and pronouns that fit their gender identity, not what is listed on legal documents, they have had to tell their teachers their correct name and pronouns for the past two years.

Whiteside described the experience of telling a teacher their name and pronouns as incredibly scary because they fear the potential rejection or discrimination they might face.

“It is incredibly terrifying the first few times you do it, and then it stays terrifying, even if, rationally, the majority of teachers at Westview are totally fine [with it],” Whiteside said. “I don’t ever believe that [rejection] will happen, but I’m still afraid that it will, because it hurts when someone messes up even on accident, and it hurts more when it’s on purpose.”

Planken shared a similar fear about telling teachers their name and pronouns. They said it feels strange to them because the cisgender students do not have to do the same.

“I feel like I’m scared to [tell my teachers] sometimes because I’m afraid that I’m going to get discriminated against,” Planken said. “Even though it hasn’t actually happened, I expect to.”

Meyer said one of the best ways teachers can make students feel more comfortable in class is by inviting them to share the name and pronouns they prefer, without needing parental permission, which could out students with unsupportive families. She also recommended that teachers have a safe space sticker in their classroom or make an inclusive statement at the beginning of the term welcoming people of all identities.

“Just providing a space for students to come forward is sometimes all that a student needs to know that this adult is going to be supportive of [them],” Meyer said. “I have my name and I have my pronouns, so it shows up in my Zoom screen so it makes it normal for people to put up their name and pronouns, not just kids who identify as trans or nonbinary.”

Planken had a positive experience with sharing their name and pronouns, as all of their teachers sent out Google Forms in the beginning of the year asking how students want to be addressed.

“It made me really happy to actually see someone ask, because everyone just assumes, and so it’s a nice change,” they said. “Usually, you have to go up and tell them like a little secret. But then [this year] it’s a normalized thing, because everyone gets asked the same question.”

Meyer also stressed the importance of creating a safe environment for transgender and nonbinary students during distance learning, as some students might be in unsupportive environments at home. She said that oftentimes, schools are safe places where trans students are free to be themselves, but distance learning can prevent that.

“Zoom names and pronouns are so important because being able to represent yourself with the name and pronouns that feel most accurate for you is really affirming and important for youth identity and development,” Meyer said. “Adolescent years are really, really important in figuring out who you are and if you’re not supported in developing the identity that feels right for you, it can be really alienating and it can cause people to withdraw.”

Fortunately, this year, Whiteside was able to get their name changed within the school system before school started, so their Zoom tag and Canvas name are accurate. They said that while parental permission is not required to change one’s name in the school systems, having parent approval is recommended; parents may see the different name in Synergy, and if they´re not supportive, it could create a dangerous environment for the student.

Planken also said that a benefit of online school is having their name and pronouns put on their Zoom tag, making it less likely that people will refer to them with the incorrect name or pronouns.

“A lot of the time with physical school, where there’s no typed words on the screen that you have to look at, people forget, people have excuses not to use [my pronouns],” Planken said. “But when they’re written on a screen, it’s like, these are my pronouns, look at them, you don’t have an excuse not to do this anymore.”

While Planken was able to find a technological workaround to add their pronouns to their Zoom tag, most students have not. As of now, the district has blocked students from changing their name on Zoom and there are no fields in Canvas or Zoom in which to write one’s pronouns.

Both Planken and Meyer said that having a space for students to share their name and pronouns over distance learning would make for a more comfortable learning environment.

“Being called by the name and pronouns that you want is really important to be able to build trust and have a sense of safety and feel respected in a community,” Meyer said.

Planken stressed the positive impact that using the right name and pronouns can have.

“Using someone’s name or preferred pronouns makes so much of a difference, it can make one little person feel so good about themselves,” Planken said. “I think that you should do that just to make a change in someone’s life.”

Whiteside said that when people referred to them by the correct name and pronouns, it feels like nothing, exactly how they want it to feel.

“I want people to just use my name and pronouns and for that to be normal,” they said. “I don’t want to have to wonder whether such and such person is going to mess it up this time or not. I want to be comfortable in my own existence.”

Embracing Gender Identity

Despite the challenges that come with identifying outside of the gender they were assigned at birth, both Whiteside and Planken said they are proud to be nonbinary because it is what feels most right for them.

For Planken, realizing they were nonbinary was a simple process, something that just seemed to click for them.

“I’ve grown up in an environment where I’ve been able to learn about changing your name, changing your pronouns, and so it was pretty easy for me to figure out, ‘Oh, hey, this is what I want,’¨ they said. “In my case, it was kind of just, I like being non-binary because I like not being forced to be confined to one specific gender identity. Having the fluidity of being neither or in the middle is what I love and that is how I like to present myself.”

For Whiteside, however, the process was a bit more complicated. They said it took a lot of experimentation and time to figure out their gender identity. Overall, they said that transitioning to being nonbinary greatly improved their life.

“There was a lot of self-doubt for me in learning to trust myself and find what worked,” Whiteside said. “But once I did, and really, I’m still working on it, I just felt such intense relief. When I was finally able to cut my hair short, it was the first time I looked in the mirror and felt a connection to that person in a long time. When you’re feeling dysphoric, you don’t recognize yourself. My appearance and presentation was wrong for so long that finding myself felt extraordinary.”

Through this time exploring their gender identity, Whiteside found support from their friends, helping Whiteside try out different names and pronouns.

“Being around supportive people lets me relax,” they said. “I don’t have to be second guessing what they think of me, or whether they understand what I’m going through, or whether they purposely or accidentally are going to mess up my pronouns or name.”

Whiteside quoted the play A Kind of Weather to describe what they were feeling: “It’s not a transition, only for other people. It’s a coming into focus.”

Whiteside said that even with the explanations that inevitably come with their identity, finding themselves and embracing their identity was worth it.

Whiteside just wants people to see them the way they see themself. After all, they said, they have spent a long time figuring out their identity, and they want people to understand them.

“I want people to see me as who I am, as the person I have worked so hard to find,” Whiteside said. “For a long time things like selfies were reminders that I didn’t like myself. But being able to affirm myself and have others do it as well makes the liking myself moments more frequent. I’m just happier now.”

Charlotte Isbister • Dec 17, 2020 at 9:40 am

I am proud of our editor in chief for this coverage and providing in depth reporting on issues important to our students and staff. This was well written and insightful. I am proud of our non-binary students for educating us, and the bravery that it takes to do so. I very much appreciate you all. I wish you normalcy. Best to you, Mrs. Isbister {she/her/hers}