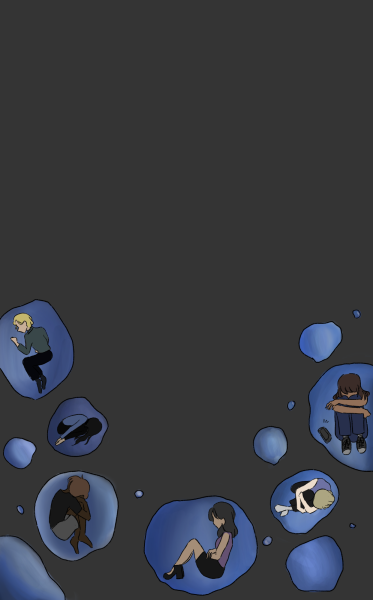

Finding Light in Darkness: Maintaining Mental Health in the Pandemic

Creating environment conducive to better mental health results in improved physical health necessary to endure pandemic

When Ben Fang (12) steps outside his house, he’s greeted with reminders.

He notices the flowers blooming, and they remind him that time is still passing. He notices the day’s shifting arrangement of clouds in the sky, and they remind him that things are still changing.

But mostly, he notices the people. Whether they’re running, walking their dog, or just sitting on their lawn, they remind him that he’s not the only one going through this. They remind him that he’s not alone.

And while that feeling lingers as he returns home, it doesn’t last forever.

Soon, Fang will find himself slipping into a strange state—a struggling feeling that often accompanies the routines of prolonged isolation that he, and many others, are now experiencing.

“I miss being able to go to my friends and I don’t think online learning adequately replaces classes,” Fang said. “It’s tough to have all my plans and intentions put on hold, so I’m simply just biding my time.”

While sunshine and exercise can strengthen our physical health, Fang mainly takes consistent walks to improve his mental health—something that health experts like Dr. Steven C. Hayes deem increasingly important during this time.

The Relationship Between Mental and Physical Health

Hayes is a Foundation Professor of Psychology at the University of Nevada, Reno and is the author of 46 books on mental health. As an expert on the importance of acceptance, mindfulness, and values, Hayes said that mental health directly correlates with physical health.

“Mental health includes behavioral health, includes behavior and our ability to step up to [challenges], and there’s no way that we can adequately maintain our physical health without behavior change in this case,” Hayes said. “This [pandemic] is not a matter of simply having an operation or taking a pill. It’s a matter of a lot of behavior change and working together with others.”

Compliance with the government’s stay-at-home orders and social distancing guidelines is a no-brainer for Fang, but he still finds himself resenting the process.

“I know it’s for the greater good to stay inside and abide by the rules of self-quarantine and I know it’s going to end soon,” Fang said. “So I go along with it. I follow the rules. But it doesn’t stop the fact that I still don’t enjoy anything about it.”

When social distancing guidelines were first enforced, Fang said that his aspirations for senior year were halted, leaving him with a lack of closure.

“[Before school closed,] I was falling into a routine and feeling comfortable with it, noticing the progress I was making towards an end goal, both in college and myself,” Fang said. “As the virus came along, I felt myself overturned from this groove that I had found.”

Though he was initially quick to acclimate to the new lifestyle, Fang said he felt himself struggling to stay grounded after about a month of being at home.

“I feel like so much of my health, both physical and mental, is grounded in maintenance,” Fang said. “It sort of hit me that this new set of circumstances had become my reality for the time being, and had the potential of being so for an indefinite amount of time.”

Despite his attempts to create a routine for himself, Fang said this heightened his feelings of anxiety and restlessness.

“I knew I was unhappy, and given that these emotions were making themselves apparent after I had been upholding a routine for quite some time, it seemed like the routine had done nothing to help,” Fang said. “But as I let myself give up on it for a few days and my mental state began to decline even further, I realized this was far from the truth.”

Though Fang had restarted the routine he tried to create for himself, he still dwelled on the past or worried over the future often.

“I found myself thinking about [the past] excessively, even though there’s nothing I can do about it,” he said. “Regret, even though it’s a very prominent emotion, it’s hard to consider it serving a purpose because you simply can’t change the past and right now, it certainly [hasn’t felt] like I have control over my future.”

This behavior, Hayes said, is an indicator of psychological inflexibility, or an entanglement of thoughts and judgements that can lead to poor mental health.

“It turns out that if we are psychologically inflexible before really challenging or difficult things happen, we’re much more likely to develop anxiety, depression, substance abuse, trauma, et cetera,” Hayes said. “So already, if people were not ready to step up to the challenge in a psychologically healthy way, problems are beginning to dig in due to the emotional, behavioral, and physical strain of isolation, uncertainty and fear.”

Mentally stepping up to this challenge is something Ella Dunn (9) has worked on for the past four years.

In sixth grade, during a test, she began to feel inexplicable pain in her back and shoulders. Her breathing became more rapid, her temperature rose and her anxiety rose with it. Having recently learned of the symptoms, Dunn began to mistake her anxiety for a heart attack.

This anxiety, which visited Dunn more and more often from that point, centered around health and safety.

“Most of my panic attacks come from medical things, like ideas of others or myself getting sick or hurt,” Dunn said. “When I see things about self defense or people getting kidnapped on the news, that tends to trigger my panic attacks.”

In an effort to contain this anxiety, Dunn began going to therapy and created a calmer lifestyle for herself.

“Sometimes I’ll feel something coming on several times a day or in a week,” she said. “I just have to figure out what’s triggering me and then eliminate that from my life for the time being.”

Though not a perfect solution, Dunn learned to avoid watching the news. She avoided circumstances that were likely to trigger her panic attacks well into high school, as well as learned to combat and dismiss her irrational fears.

But as the threat of COVID-19 worked its way from distant countries overseas to California, her irrational fears became potential realities.

“I’ve always had fears of losing myself or my friends and family,” Dunn said. “It’s very anxiety-inducing because once I have a thought about death or bad health, it gets me into this cycle of all the possible ways I could die during this pandemic.”

Dunn said that this fear of uncertainty was perpetuated by the abundance of media speculation, as self-quarantine guidelines began to be put into place.

“There was so much chaos and so many questions,” she said. “The newness of all of it was also what scared me, but I’ve realized now that I shouldn’t be watching the news because it freaks me out.”

According to Hayes, this fixation on the uncertainty of a situation makes it more difficult to come out the other end of a challenging situation.

“Intolerance of uncertainty is a form of experiential avoidance,” Hayes said. “We live inside the moment with uncertainty about the future. In situations like this, that makes it really obvious, but it’s always true. If you’re not open to that, [you’re less likely] to absorb the losses flexibly and focus on what’s important and keep moving.”

Building a Mentally Healthy Routine

Fang said that he has experienced a fear of uncertainty similar to Dunn’s. Both found that blocking out news sources, while checking in enough to stay informed, has allowed them to focus on themselves in the present.

“I’ve been focusing on reassessing my core values,” Fang said. “I feel like this is the perfect time to take into account what I think or what I thought I held important in my life and reconsider. On one part, I’m holding dear to what I do consider worthwhile and on the other part, casting aside what I’ve decided against, and I suppose, filling in the gaps with new things to try.”

Hayes said that this assessment of values is the first step to creating a mentally healthy lifestyle through meaningful activities.

“You need to be able to identify your values and create value-based habits,” Hayes said. “[Psychologically] rigid folks tend not to have meaning by choice. Their behavioral patterns tend to be either chaotic or rigid, and not driven by chosen meaning and purpose.”

By assessing his own core values, Fang has developed a stronger sense of purpose which, he said, grounds him mentally.

But this focus on the self has also led to a natural disconnect from friends for both Fang and Dunn—a disconnection that leaves Dunn specifically without social distraction from her anxiety.

“Being with my friends keeps my mind going and distracted,” Dunn said. “I [used to have] a lot going on, so my mind wasn’t really going super deep or overthinking things in a bad way. We could talk about school or what was going on in our classes, but I feel like now we just don’t have a lot of conversation points and we can’t go out together anymore.”

She has overcome the challenge of social isolation by taking up new hobbies. With more time, Dunn has started learning guitar and picked up drawing and reading again—two activities that she said she used to do often.

“These things help me fill up the time that I would be spending thinking and overthinking,” she said. “I’m taking my mind off of things and going into a new world when I read, and I’m using my mental energy to learn something new with guitar.”

Fang also began to fill up his time with new and old activities. He started working out, writing, and cooking. He even plans on beginning to sew.

Although they help to keep his mind busy, he does find himself comparing his current days to the past again.

“I’m very much lonely and wanting the company of my friends, but also wanting the familiarity of routine and being able to do things that I used to,” Fang said. “I’ve built my own new routine and sort-of substituted. I know it’s not an adequate substitute, but it’s the best I have.”

Hayes said that building structure around meaningful activities, so long as it doesn’t develop into overworking and sublimation, provides purpose that will often keep us from declining mentally.

“You [need] those kinds of flexibility skills of emotional-cognitive openness,” Hayes said. “Having a mindful and aware sense of self, being able to allocate attention in the present moment, and being able to choose what your values are [can allow you] to put them into your behavior by choice and build habits around it.”

Fang said that he’s become particularly fond of engaging in physical fitness activities, both for the way they make him feel and the sense of direction they give him.

“[These activities] all pass time in the day, which is what I guess we’re all trying to do, just make the days go on until something changes,” Fang said. “But physical fitness is also a sign of progress and seeing the difference that it makes, keeping up a scheduled routine, it shows me that time passes, that I’m not at a standstill and that’s comforting.”

While creating a meaningful routine, maintaining physical health through exercise and getting outside often are all helpful, Hayes said that the goal of improving the physical state is also partially to improve the mental state. Ultimately, our fixations, worries and judgements must be recognized, not repressed.

“You need to let go of entangling thoughts,” Hayes said. “It’s not helpful to beat yourself up or criticize, challenge and change irrational thoughts because it puts more focus on them, and that’s the last thing you want to do. What you want to do is back up, let the thoughts that aren’t helpful go and focus on the ones that are.”

Staying Grounded in Reality, Positivity

Dunn built this habit of redirecting her thought process through the hobbies that she picked up. By allowing herself to be distracted from her irrational worries built on speculation, she was able to bring the safety of her situation into focus in therapy.

“When the virus started getting serious, I told [my therapist] about my fears, but we discussed how my family is doing really well in this,” Dunn said. “We’re being super careful not to go out and to clean everything in the house. So she helped me realize that I’m actually in a very secure spot, and that I have no reason to have personal fear for me or my family right now.”

Fang found a similar kind of control over his thoughts—a control rooted in consistency.

“I feel best on the most uneventful days,” Fang said. “It seems almost ironic, but it’s the days in which I’m able to maintain a routine and everything goes as expected that feel the most comforting. I feel the most in control, especially in these very testing times, and that’s when I’m the most content.”

Hayes said that this connection between contentment and sense of control has been proven time and time again. By redirecting our thought process, he said, the worst of obstacles can become a challenge easily overcome.

“Some people, when they face a challenge like this, are shown to be better off after the event despite the challenge, because they will have mastered it and learned a lot by the challenge,” Hayes said. “There’s a number of things that are negative at the time, but positive over time because they taught us important lessons.”

Dunn has found importance in confiding in the right person, not merely looking for distraction. Rather than get out her phone to text a friend, she now talks through her fears with a family member.

“I can go to my dad if I want him to feel no pity for me and tell me I’m being insane, or I can go to my mom if I want someone who’s going to be super-sympathetic,” she said. “Choosing the right person to go to has been important in helping me calm down.”

Within the first week of social distancing, Dunn was sitting on the couch with her family, watching news on the virus when she was visited by her anxiety once again.

“I just started to gradually build up to this point of high anxiety, and I just looked over at my dad and he could see what was going on in my face,” Dunn said. “I asked if we could just talk and so we had a conversation in the garage. He explained to me why we’re perfectly safe and how we’re handling it, and that really helped ground me.”

While Dunn finds comfort in keeping herself in the present, Fang achieves peace of mind by creating a positive version of the future in his own head.

“In the moments that I do think about the future, I find it really cathartic,” Fang said. “Right now, we’re living in a very uncomfortable time and it’s very reassuring to put myself in a situation where, as soon as it’s over, I can slide back into comfort. It’s like I’m setting myself up for success.”

Fang said that he’s able to create this positive future for himself in a few ways: imagining his time in college, seeing the progress as he works out, and supporting small businesses.

One of Fang’s biggest worries about the pandemic, he said, is over the small businesses and restaurants that he normally loves going to. To combat this, he helps where he can financially.

“I try to still buy from the [establishments] doing takeout and delivery, when possible,” Fang said. “It’s not as gratifying, not being able to enter their store and enjoy their services in person, but it’s a delayed gratification. I know that in the end, being able to walk out of this and go to those restaurants again will make it all worthwhile.”

Hayes said that finding small ways to help, as well as thinking about isolation as helping in itself, can help us to gain a sense of control and, ultimately, a better outlook on the situation.

“People can shift their focus to staying home not because they’re afraid, or because they have to, but because they care about their family, community, the world,” he said. “This is their opportunity to be a kind of coronavirus hero.”

Helping others or not, Hayes said that he stresses the priority of taking care of ourselves mentally, in whatever form that comes. At times like this, finding out what truly matters to us and sticking to that is the most powerful mental tool.

“During the crisis, people can acquire psychological skills to be able to walk through a challenge like this and come out on the side with post-traumatic growth,” Hayes said. “The ability to learn lessons comes from the type of psychological adjustments we make during and after the challenge.”

For Dunn, it’s learning not to focus on the news or the negative, then engaging in creative pastimes and confiding more in her family.

“After I had that conversation with my dad, I just kept replaying his words in my head whenever I felt like I would work my way back up that slope of anxiety,” she said. “It’s happened a few times in the past few weeks. Every time that I talk to someone else, it usually has a better outcome.”

And for Fang, it’s the progress he gets when working out, the way the green grows over once-trampled trails nearby—the simple reminders that the world is still moving along, and that while he may feel alone in that house, he is anything but alone.

Carolyn couch • May 2, 2020 at 10:46 am

Blake, a very introspective article also filled with good medical advice. A good read for all ages. You have spent many hours I’m sure researching this article. It shows and it will be a source for helping others and, I venture to guess, yourself as well. Thank you . You do have another gift besides music. Meema