“Tropical” is the word Danielle Erickson (12) uses to describe her dad, Tim. After all, nearly everything he wore, listened to, or surrounded himself with consisted of colorful prints of lush flowers, the reverberating synths of the steel drum used in almost every vacation getaway soundtrack, and scenes of island escapism plastered on his room’s walls. He sported Tommy Bahama Hawaiian button-up shirts any day he could and played ’70s pop star Jimmy Buffett’s hit “Margaritaville” on repeat. While these are the little aspects of her dad’s character that Erickson fondly remembers, softball was the common thread between the two.

When Erickson was 6, there was never a time her dad wasn’t on the field alongside her, cheering from the dugout or coaches’ box. That year, she played her first season for the PQ Girls Softball Association. In recalling her non-competitive ball games and practices, all she can remember was the fun seasons she had with her dad; how carefree and enjoyable a non-competitive league should be.

“I never had a harsh practice with him,” Erickson said. “Everything was light-hearted and fun. He always made sure to include every girl and focus on the goods—not always the wrongs. He knew how to talk to people. He knew how to make someone feel better. He loved helping kids out and seeing them grow into mature people.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Erickson was keen in educating Erickson on the basics: to communicate, stay active, and overcome obstacles as a team. When Erickson tended to pull her head out at the plate, her dad suggested that she bite on her collar—a trick he used when he played baseball.

“I think of him when I do that little stupid thing,” she said through a smile. “It helps, though. It really does. You look stupid, but it helps.”

When Erickson was 10, she and her dad rested on the stands after practices, watching the older girls. She observed the 14- and 16-year-old players’ larger stature, knowing that she wanted to grow and progress to a higher level under her dad’s guidance. From the different divisions—PQ Lightning, Thunder, and All-Stars—Mr. Erickson was with her each step of the way. In doing so, Mr. Erickson became an integral part of the softball community, serving as the league’s president for three years.

Maybe Mr. Erickson would have continued for another year, if he wasn’t diagnosed in 2012 with melanoma, a severe form of skin cancer. While her mom and dad kept the details of her dad’s illness vague to their kids, regular trips to the hospital became normal for Erickson. On the weekday appointments, Erickson left for the hospital with her dad, mom, and younger sister, Hanna, directly after school. There, the three sat in the waiting room until the painstaking two to three hours were up.

Chemotherapy seemed to work, as Mr. Erickson didn’t return to the hospital for six months after his treatment. Life seemed to resume for a while. After turning 14, Erickson joined a competitive travel team with eight years of playing experience under her belt. She acclimated to the higher playing level quickly and even though this was her first season without her dad as the coach, when she peered into the dull grey stands, she still saw her dad at the games closer to home, perched on a bench. Tangible and resonant. He hollered Erickson’s teammates’ names, and when Erickson came to bat, he called her by her nickname, D.K., encouraging her keep her eye on the ball.

“He was one of those obnoxious parents, but in a good way,” she said. “He was always cheering on people.”

Despite a half-year break from treatment, shortly after Erickson started travel ball, her dad started an extensive form of chemotherapy that required three to four appointments each week. Even then, she remembers how he managed to grin.

“When he was in the hospital, he always had a smile on his face,” Erickson said with glassy eyes. “I think he tried to protect us and hide his pain from everyone. I didn’t know that at the time, but now I know when I think about it. There wasn’t a moment where he wasn’t smiling, laughing, or trying to say something funny. That was the kind of person he was.”

In December 2013, Mr. Erickson decided to quit treatment and retire to his home, transforming his master bedroom into a makeshift hospital room. The family was equipped with a bulky hospital bed and a hospice nurse who cared for Mr. Erickson during the school days. He and his wife ensured that their daughters remained sheltered from the realities behind the move. Seeing the hospice nurse a total of two times, Erickson said she only knew of an obscure person who came in and out of the house, treating her bedridden dad. The nurse arrived after Erickson and her sister left for school and made sure to leave before they returned home.

The month Mr. Erickson returned home from the hospital, he called his daughters into his room and explained what the transition meant.

In coping with her dad’s battle against melanoma, Erickson’s experience consisted of stark contrasts between normalcy and sudden change. One school day, Erickson was checked out from school by her step-sister. After they picked up Hanna, they drove to the movie theater and watched Frozen, a family outing that Erickson was suspicious of because the impromptu nature of it.

In one moment, Erickson was watching an animated, Christmas-orientated movie. The next, she was sitting beside her dad’s hospital bed with her family. While her sister cried, Erickson didn’t shed a single tear; nor did she choke back any. At the time, she did not want to let the news sink in.

“I was not fully accepting it yet,” Erickson said.

But throughout the course of two months, she noticed the rapid change in her dad’s condition. For one moment, her dad cracked a joke in the hospital. The next, he resembled what Danielle described as “withered.”

“[He looked] older than how he should have looked,” she visualized. “He looked broken down and more broken than how he should have looked. I could tell because he had a bunch of scars on his face from the chemotherapy. But I never thought about it as anything. There were little things I didn’t ask him about, but I knew that it was a sign of what was going to happen.”

In late February 2014, Erickson and her sister received what Erickson refers to as “the final talk.”

The tropical paintings. The opened windows that allowed natural light to flow in. The pictures of the family of four on a camping trip, resting on the nightstand table that stood beside her dad’s hospital bed.

It was a little too much to bear, but she didn’t like crying. She still doesn’t. But unlike the conversation she had with her dad in December, she struggled to suppress tears and fully absorb her dad’s words.

He told his daughters that he loved them, that they need to pursue goals that make them happy, that there is no one to blame for his illness. He attempted to offer every life lesson a dad could give his children in a lifetime, all in the span of a couple minutes.

“He was honest about everything—honest in the happiest way possible—trying to skip around certain things that he knew would trigger us to bawl our eyes out,” Erickson said. “There wasn’t much I could do about it so I just listened to what he had to say.”

March 15, 2014 was the day she started describing her dad in past tense. That evening, Erickson, her mom, and her aunt congregated in the living room and tuned into a movie when the baby monitor in Mr. Erickson’s room went mute.

“We stared at each other, and my mom ran upstairs to check,” Erickson recollected. “My aunt stayed downstairs with me, trying to hug me. I told her to go stay with my mom. She said that she wanted to stay and comfort me. My little sister had to get called up from a sleepover to come home to that.”

Wear became wore. Listen became listened. Surrounds became surrounded. She lost her greatest coach, cheerleader, and dad. Right after he passed, the family added his handprint to a ceramic sheet that already had the rest of the family’s handprints. While she doesn’t know whether she wasn’t allowed to or if she missed the opportunity to help pack her dad’s belongings, Erickson came out of her room finding her dad gone and his bed empty.

For a couple days, she sought refuge in her room, caught in a daze between sleep and binge-watching movies.

“I didn’t talk to anyone for a while,” she said. “I felt like I was on my own, but I knew I wasn’t. I definitely chose to [feel that way]. I was an introvert for the rest of the year.”

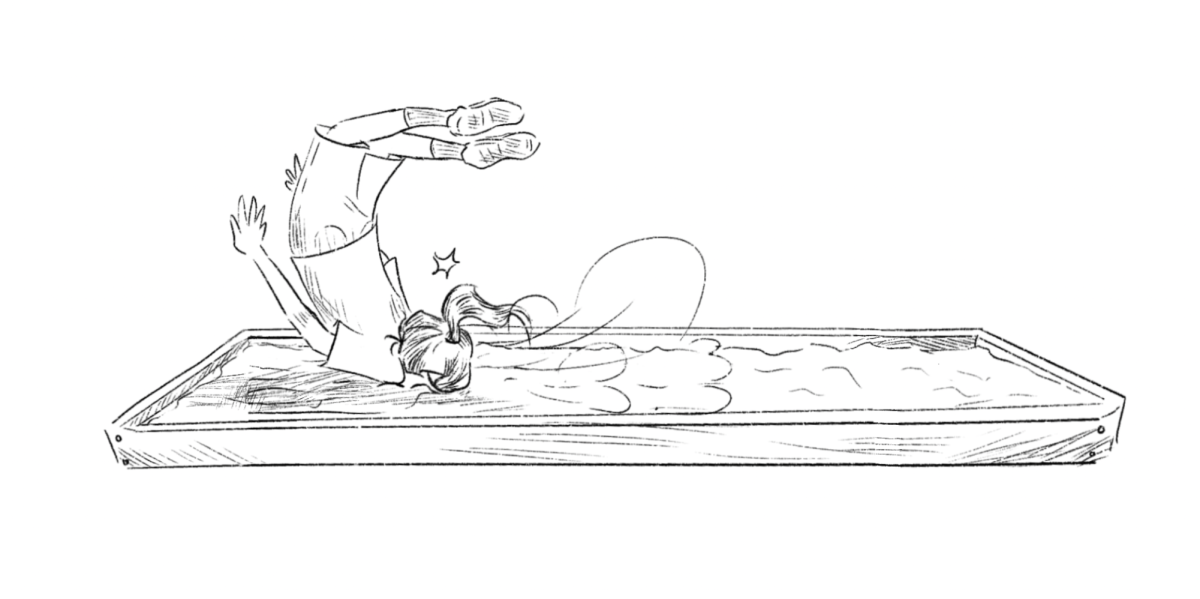

But she chose to continue playing softball, rejoining her travel team a week after her dad’s passing—simply because she missed being on the field, a place that she was used to. Playing prevented her from getting lost in her head. While Mr. Erickson stressed in their last conversation to not do anything for him, Erickson said she started playing for him a year before when he was first diagnosed.

“When I was younger, I just played because I didn’t know any different,” she explained. “[I played] because everyone I knew played, and it was fun. Once he started getting sick, I wanted to keep playing for him.”

At the moments where the game didn’t seem as lively and enjoyable as Erickson remembered it when her dad was alive, that sense of obligation felt like a burden. One of the paramount pieces of advice Erickson was taught through her dad’s coaching was to never give up. While Mr. Erickson ultimately had to give in to his illness, Erickson said she felt that if she quit softball, she would be admitting to defeat.

“I felt guilty about it because I wanted to keep playing for my dad,” she said. “That is the hard part. It’s weird to think that I don’t ever want to give up, but my dad didn’t have a choice. But it’s odd when I wondered why now? Why did everything happen so fast and when we were so young?”

In the beginning of the school year, she considered missing her senior season. However, after taking a new perspective of focusing on the core reasons why she chose to continue playing the sport after her dad first introduced her to it, she decided to do otherwise. In her 12 years of playing, she made friends, many whom she met when her dad coached—some of whom are on the varsity team and are her support system.

“I didn’t regret [returning],” Erickson said. “It was worth it to keep playing.”

Erickson is on a scholarship to play D-III softball for Olivet College in Michigan. Although she’s grown to be a competitive left-fielder and pitcher, she hopes to just have a fun closing season.

“[I want] to enjoy every last moment of [the season] no matter if we are winning or losing,” she said. “I can never come back to this season after this year.”

While it has been exactly three years since Mr. Erickson has passed, there are still pieces of him in Erickson’s home. A portion of his ashes is kept in a box on her dresser, along with another portion encased in a bracelet bead. She also keeps some of her dad’s shirts and jackets in her closet along with her everyday clothes. Her favorite item is one of her dad’s sweatshirts: a Tommy Bahama, cream-colored, collared, half-zip up. Slightly oversized, but nice to wear, she said. But most importantly, it was his.