A Helping Hand

Despite the cultural stigmas surrounding mental health treatment, therapy benefits anyone who needs emotional support

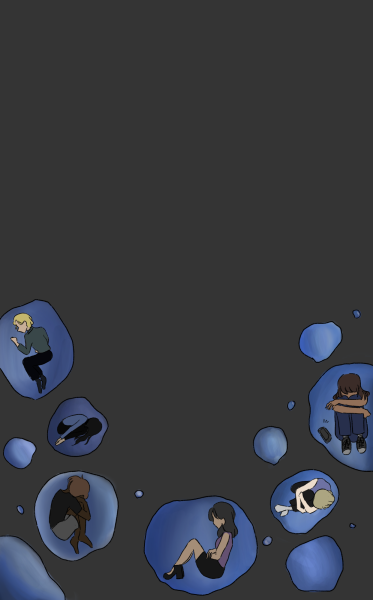

Lamees Kazi (11) would sit in a classroom and just panic.

It wasn’t the fear of a math test or the intimidation of a strict teacher. It was any harmless situation—a noisy class, a Socratic Seminar—that would set her off, until she was lost under waves of paralyzing anxiety.

“Before I even knew what was causing it, I would start hyperventilating and I wouldn’t be able to stop,” Kazi said.

The shortness of breath and the overwhelming sense of terror were indicative of the beginning of a panic attack. Kazi didn’t know what was happening. All she knew was that she needed help.

According to Neal Swerdlow, a psychiatry professor at UCSD, distress—a broad term for anxiety—is the most common reason why people see a mental health professional.

“[The only thing] that people are able to discern at that point in time is the fact that they’re experiencing distress,” Swerdlow said.

Though Kazi has never been formally diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, she is one of 30 million people in the U.S. who benefit from psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy, or “talk therapy,” operates under a humanistic perspective, which involves regularly talking to a trained therapist in an attempt to achieve personal growth and overcome difficulties.

However, potential psychotherapy patients can be discouraged because of a stigma surrounding therapy, according to Professor Philip Sayegh of the UCLA Department of Psychology. Sayegh’s Sociocultural Health Belief Model, a conceptual model of research, illustrates how various levels of cultural assimilation and the perception of the severity of mental illness greatly influence one’s decision to seek care. It further conveys how individuals who attend therapy may worry that they will be devalued or disgraced because of this stigma.

Part I: Holding Back

We can’t see mental illness.

When doctors tell parents that their child has a broken leg or measles, parents likely take immediate action to fix it. They see their child in physical pain, undeniably struggling. However, because mental illnesses are often intangible, they often fly under the radar. According to a report from the World Health Organization, nearly two-thirds of people with a known mental disorder never seek help from a health professional. Invisible, elusive monsters, mental illnesses are hard to catch and even harder to kill.

“The problem with most mental illnesses is that the parts of the brain that are affected are the ones that control thoughts and feelings, which are not things you can see,” Swerdlow said. “That makes it harder for people to understand and accept [their illness].”

When parents fail to acknowledge mental illnesses as a real problem affecting their children, it becomes even harder for the family to talk about it in the household, permanently dismissing the possibility of of their child having a mental illness.

According to Swerdlow, many cultures view psychological symptoms differently, operating under different belief systems that drive the way they treat mental illness. Societal traditions and a lack of awareness play a part in some cultures’ stigmatization of therapy, which further discourages people from seeking help.

Sayegh said that different cultures have different perceptions about mental health, including the causes of mental illness. While some cultures view mental illness as a biomedical problem, others see it as a curse from God or having “bad blood.” For many people coming from South Asian cultural backgrounds like Kazi, the cultural approach is to simply not talk about mental health at all.

“I grew up in a Pakistani-Indian family, and [mental illness] was never really a discussion at all,” Kazi said. “It’s all very hush-hush.”

Whether it was in regards to Kazi’s own struggle with anxiety or that of her relatives, her parents always tiptoed around the topic of mental illness. Because of this, Kazi said that she felt as if she was being unnecessarily dramatic or attention-seeking for expressing symptoms of anxiety.

“I felt like I wasn’t normal or that I couldn’t be open or comfortable, even in my own home,” Kazi said.

A negative view of mental health isn’t exclusive to the South Asian culture. While Gabriel Maya (11), was free to talk about his emotions at home, he knew that his Latina mother did not share the same luxury growing up.

“If she ever opened up about her feelings and talked about what was going on to her dad, she would’ve been slapped,” Maya said. “She would have been belted and told to get over it.”

Like so many others suffering from mental disorders, he bottled his feelings up instead of dealing with them. As a result, his internal problems were dismissed and he suffered in silence.

Maya was no stranger to mental illness. Growing up, he watched his older brother Nicholas slip away as mental disorders took control of his life. Scared by his brother’s downward spiral, Maya attempted to tackle his own depression and mood disorders by himself.

“I thought, ‘I’m tougher than my brother, I can survive [my mental illness] longer than my brother,’” Maya said.

Maya said he thought that he could get over his mental illness. He thought he could will his brain to fix itself, to cooperate.

But he couldn’t. Maya soon found himself going down a dangerous path as an escape from his distress.

“In the process, I was being really self-destructive with my relationships with people and I ended a lot of them,” Maya said.

Kazi’s anxiety also began to negatively affect her life. The littlest things would upset her, making her irritable outbursts at home and poor performance in school worse. The mere sound of pots banging in the kitchen brought Kazi close to tears. Though her mother noticed Kazi acting overly emotional and temperamental, she attributed these feelings to normal teenage behavior. But by doing so, her mother dismissed the possibility that Kazi needed professional help.

“Since no one around me seemed to want to talk about [mental illnesses], I worried that my problems weren’t really problems at all, or that everything I was dealing with was just in my head,” Kazi said.

She once interpreted her friends leaving her at a mosque as them abandoning her. Within seconds, she was hyperventilating and frantically pacing. Kazi knew that her reactions to certain situations were completely irrational, but this only made her more reluctant to seek therapy, thinking that she could pick apart and fix her symptoms alone.

This disregard for one’s problems and the negative attitude toward therapy can delay the start of treatment. According to Swerdlow, this means that by the time people go in for help, their problems have worsened and their illness is ultimately harder to fix.

Sayegh said that part of the stigma and the resulting dismissal of therapy as an effective form of treatment lies in the misconception that it is reserved for violent criminals or for the seriously disturbed. This is fueled by the portrayal of therapy in movies and TV shows.

“Keep in mind that TV is designed for entertainment,” Sayegh said. “It is often highly dramaticized and portrays ethical violations that most therapists would actively avoid.”

Adding to the feelings of distrust towards therapy is the fact that many forms of non-evidence based therapy are commonly advertised to those looking for answers.

¨There are a lot of funny kinds of therapy out there, that are not science based,” Swerdlow said. “They don’t help people and instead can be detrimental.”

Websites, quizzes, and online medical “professionals” offer up diagnoses—with varying degrees of accuracy—to anyone who takes the time to look. But what these resources don’t provide are the realistic steps to proactively fix the issues they claim to identify. So when individuals are faced with inner conflict but are given no definite way to solve it, a sense of helplessness sinks in.

“Part of having a mental illness is the doubt that you can be helped,” Swerdlow said.

Maya was educated on the benefits of mental health treatment but still resisted it, adamant that nothing could possibly work for him.

“I didn’t want therapy because I didn’t want to acknowledge that there was a problem with me in the first place,” Maya said.

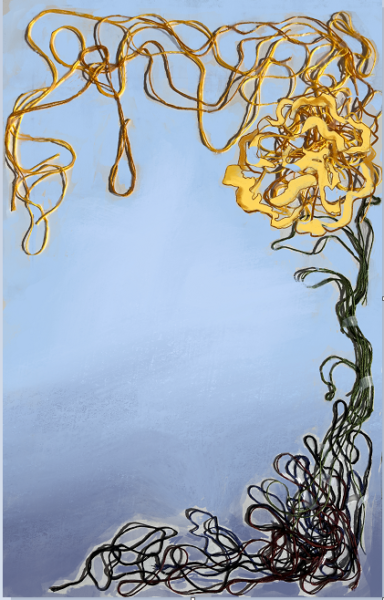

People’s perception that their mental illnesses cannot be solved through therapy generates an unhealthy cycle of distress that only continues to grow when left untreated.

“People are threatened and scared by the concept that their brain is not working right,” Swerdlow said. “Quite often the fear of uncovering and understanding that problem is greater than the distress that it causes, and at some point the balance shifts.”

At that point, when their symptoms are suddenly more traumatic than their fear, individuals generally seek professional support.

For Maya, this shift was strikingly clear: his overwhelming distress built up. School became meaningless. An entire week passed where Maya stayed in his room, feeling empty.

He was existing, but he wasn’t living.

All of these feelings built up until they drove him over the edge, leading to his suicide attempt last February.

“After trying to kill myself, I finally came to terms with my problems,” Maya said.

He knew he could no longer try to beat his symptoms alone. Finding himself in an in-patient facility, he finally realized that he needed to see a therapist.

Part II: Reaching Out

“I need help.” These are tough words to admit, but Sayegh said that crossing the mental bridge between avoidance and acceptance is a necessary step in treating any mental illness.

According to Sayegh, therapy’s introduction to the family conversation can generally be ill-received, depending on various cultures’ degree of assimilation. Sayegh said that some cultures have varying amounts of trust in mental health services and often prefer culture-specific treatment rather than Western treatment, including therapy.

Therefore, although the decisive shift from fearing to accepting mental illness allows people to take a chance and seek help, therapy is often still clouded in feelings of shame and affects relationships at home.

“My grandfather lives with me, and because of the disconnect between cultures, I still haven’t told him that I go to therapy,” Kazi said. “My mom just has me tell him that I’m going to the eye-doctor. It’s become so normal to not mention it or to pretend like it’s not a part of my life.”

Kazi’s mother, Uzma Kazi, was born and raised in Kuwait until she was 30, when she moved to the U.S. According to Mrs. Kazi, therapy was unheard of in her community. General feelings were talked about, but “irregular feelings” such as anxiety or depression were not.

“We were not even aware of regular mental health issues,” Mrs. Kazi said. “There was no gray area—it was black or white. You were either normal or crazy.”

When first introduced to the idea of therapy in the U.S., Mrs. Kazi carried that engrained skepticism and suspicion toward mental illness.

“I thought ‘Kya bakwaas hai!’ [what nonsense is this!]. Therapy sounded like a waste of time and money,” Mrs. Kazi said.

Deep down, her greatest worry was that the Desi community would shame her daughter if they found out she needed a therapist.

“Negative gossip, especially about mental health, can impact the opinions of families of future suitors,” Mrs. Kazi said.

So when the issue that once elicited a “get over it” became a serious cause for concern, Mrs. Kazi worried about how therapy may impact her family’s reputation.

“My mom goes to parties and they’ll talk about ‘my child at Harvard’ and ‘my child at Google,’” Kazi said. “But they won’t bring up anything that’s wrong.”

As exemplified by Mrs. Kazi’s cultural background and mindset, needing therapy is too often seen by parents as a character flaw, a testament to one’s failure to function. Even when an individual makes peace with the fact that they need help, they may still carry the fear of judgement from others.

“There’s a Hindi saying, ‘log kya kahenge?’ which means ‘what are the people going to say?’” Kazi said. “It’s a cultural thing. You want to just compose yourself and not seem volatile.”

However, the shame associated with therapy does not only stem from family or cultural pressures. Shame is often self-inflicted, as was the case for Maya, who said he initially viewed his need for therapy as a personal weakness.

“It was all internal,” he said. “I was just judging myself. I felt like I was weaker for reaching out and needing assistance.”

The shame was constant. Everytime he lost a wrestling match, he would blame it on his mental illness. Everytime he talked to his coach about leaving practice early to see his therapist, he would feel nothing but intense shame. It was a constant burden, to try to bury the fact that he went to therapy.

Waking up in an in-patient facility days after his suicide attempt, Maya was skeptical of therapy. He didn’t trust the facilitator who greeted him. He was asked questions like “What gives you anxiety?” and “When was a time when you felt most in control?” in an attempt to get him to talk about his feelings. Maya barely cooperated.

Still, over time, he began to comply. He did was he was told. He decided to stick with the program until he eventually he found a form of psychotherapy and a therapist that clicked with him, and he said the outcome has been positive.

“There are some days where it’s obvious that progress has been made and I can’t help but feel glad,” Maya said.

Part III: Bridging the Gap

With advances in clinical science and mainstream cultural shifts, Sayegh said that the attitude toward therapy has become more accepting over the last couple of years as a mental health resource. According to Swerdlow, over the last couple decades, there has been a concerted effort to identify an evidence-base for different forms of therapy and systematically study how therapy works, how well and for whom.

“There is no rule that says you have to have a diagnosis to pick up a phone and make an appointment to see a therapist,” Swerdlow said.

Swerdlow says that once people let their guards down, overcome the stigma, and mentally open up to therapy from an unbiased perspective, therapy can finally be used to address bigger mental issues at hand.

“The important next step is to work with someone and find out what’s causing their problems, which can be approached over time,” Swerdlow said.

For Kazi, therapy doesn’t mean a daunting psychiatrist, lab coats, or ink blot tests. Instead, it just means a safe space and a weekly mental checkup.

The activities and discussions are often loose and casual. Starting with the simple question of “How are you?” psychotherapists help people talk out certain factors that may cause distress. Patients are taught simple coping mechanisms and mindfulness exercises to help them work through their struggles.

Therapy uses a collaborative form of treatment called Collaborative-Behavioral Therapy, which focuses on the connection between thoughts, behaviors, and feelings. With a success rate of 75 percent, therapy in the real world is much more professional, focused, effective, and meaningful.

Clinically diagnosed or not, anyone can utilize therapy as a resource to figure out their strengths and weaknesses or to talk out their situational problems under the guidance of an unbiased professional.

“You’re ultimately going to therapy to help yourself, and with time, I’ve realized that there’s nothing wrong with that,” Kazi said. “It’s a resource.”

Now, in those moments when Kazi feels herself start to lose control, she knows how to react. With the help of her therapist, Kazi has found and practiced the coping mechanisms that work best for her: breathing exercises and “grounding” activities—exercises that bring her back into contact with the present moment. They are little forms of distractions to take her mind off the greater distress at hand. For Kazi, admitting she needed help wasn’t a form of weakness. It was a form of strength—the strength to finally accept and tackle her problems head on.

“I feel more in control of my physical and emotional reactions,” Kazi said. “It’s not perfect—I still struggle with anxiety on a day to day basis, but therapy has given me the tools to calm myself down and cope with my problems, which I always thought were unfixable.”

Once one overcomes the stigma against therapy as a significant barrier standing between them, they can finally take steps in the right direction to receive help. That’s why therapy exists. That’s why Kazi practices mindfulness with her therapist once a month and why Maya goes in for dialectical behavior therapy.

To get better.

“It’s a lot of heavy lifting mentally,” Maya said. “You have to put in the work to better yourself, and I think that’s the daunting part.”

According to Swerdlow, approximately 80 percent of people who receive mental-health services rate their experience as a positive one.

Swerdlow said that if more people understood that there are several forms of standardized therapy, they would be more open to mental health treatment.

“Since getting therapy, [Lamees is] more positive, and smiling a lot more,” Mrs. Kazi said. “If she’s happy, I’m happy.”